From 'Shock and Awe' to Systemic Enabling

Topics

Next generation learning is all about everyone in the system—from students through teachers to policymakers—taking charge of their own learning, development, and work. That doesn’t happen by forcing change through mandates and compliance. It happens by creating the environment and the equity of opportunity for everyone in the system to do their best possible work.

How New Hampshire is Charting the Nation’s Course for the Next Era of Education Reform

The successful, bipartisan (what?) effort to revamp the nation's core set of K-12 education laws essentially puts an end to one generation-long era of school reform—let's call it Standards Push—and ushers in the next.

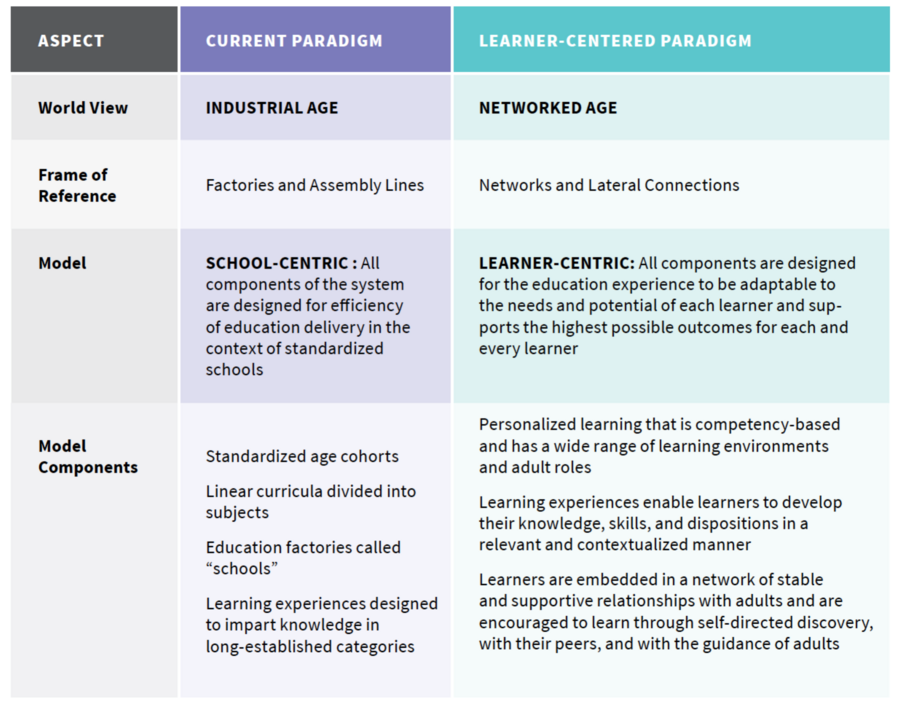

It’s too soon to label this new era, but there is a growing sense of what it needs to reflect. Of all the From This / To That tables I’ve seen lately, this one from Education Reimagined, an initiative of Convergence, developed over 18 months of effort by a committee composed of union leaders and libertarian philanthropists and advocates of every stripe in between, seems readily on the mark:

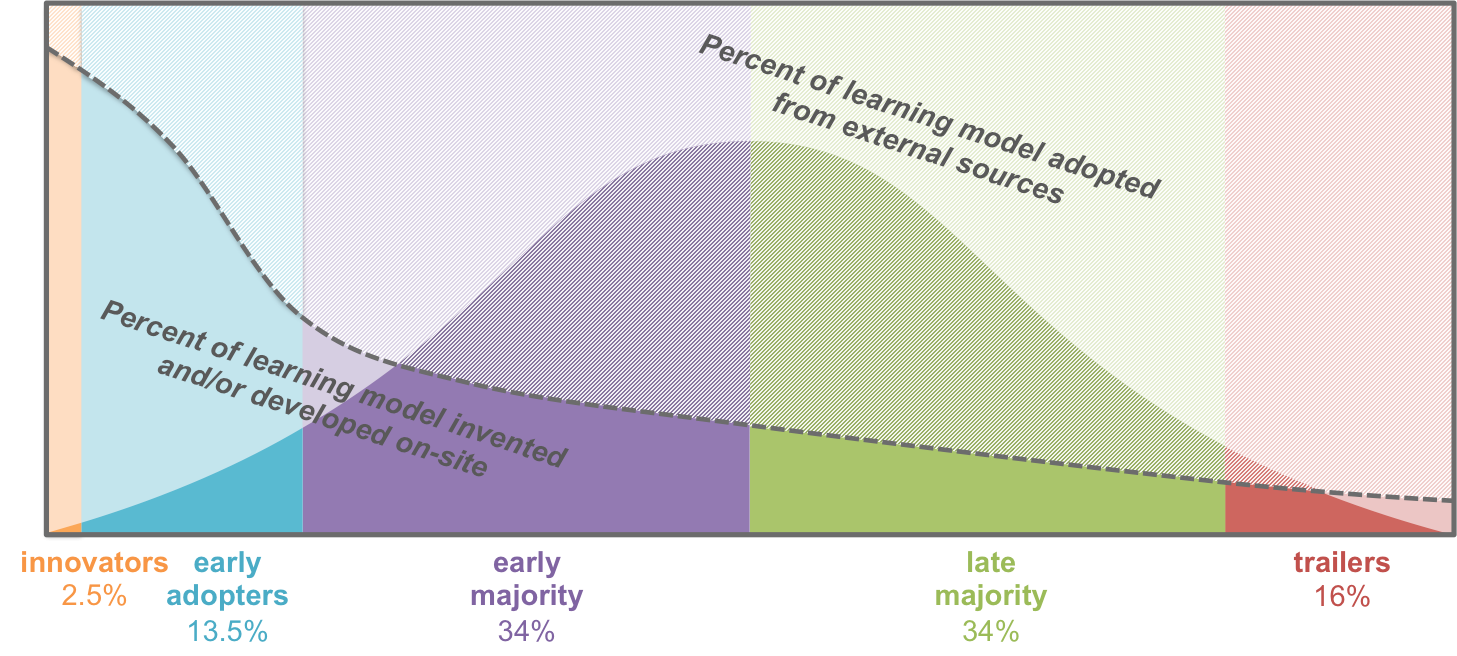

Big changes afoot, and it’s about time. The steepest challenge in moving toward this new paradigm, however, may not be the re-imagining of students’ experience of “school” and the fundamentally different learning practices that reflect the model components defined by Education Reimagined in this table. That’s already happening nationally, among the 2.5 percent in the “innovator” slice of the classic innovation adoption curve, shown below. Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC), the Hewlett Deeper Learning Network, Digital Promise, EdLeader21, and NewSchools Venture Fund (not to mention the forthcoming XQ SuperSchools) are supporting genuinely inspiring work by educators in hundreds of new-design or conversion schools nationwide.

Neither does it lie in defining the new, twenty-first-century goal-line for high school graduates that represents the North Star for these new learning designs. This has been a regular hothouse of activity for researchers, philanthropists, and non-profits for years. NGLC’s MyWays project has identified more than 20 major definitional frameworks, most with a great deal of overlap, and will be publishing our open-access distillation of those frameworks in early 2016.

No, the steepest challenge lies in assisting tens of thousands of schools occupying positions further out on the adoption curve to migrate toward the new paradigm with reasonable fidelity to its central tenets.

Here’s why:

Much of what we know about how to catalyze broad changes in American public school practice fundamentally conflicts with the very practices we now want to catalyze.

The Standards Push era triggered deep, widespread changes in school practice through the use of heavy policy artillery. State and then federal mandates, often tied to funding and backed by tests that dictated student advancement, reshaped everything from district budgets to teacher evaluation. These were the policy equivalent of what the military used to call “Shock and Awe” tactics: blunt imperatives to force immediate behavior change. On that metric, they certainly succeeded—though, like Shock and Awe, they also produced considerable collateral damage and a host of unintended consequences in terms of narrowed curricula, test-prep hysteria, and teacher (and student) disenfranchisement.

The new era, which is in part a direct response to Standards Push, rests on the conviction (well supported by research) that people—all of us, not just children—learn best under these three conditions:

- When the learning has meaning and intrinsic purpose

- When it actively engages the learner in real or authentic contexts

- When the learner—in the case of K-12 students, assisted by professionals—has some degree of ownership and control over the form and pace of the learning.

This new era for public education isn’t simply a push back at Standards Push; it reflects the pervasive current across many dimensions of modern life, generally fueled by technology, toward customization and the Personalization of Everything.

This form of learner-centered education takes root in environments in which everyone—adult and child alike—is granted appropriate degrees of responsibility, where agency, self-efficacy, and collective purpose have replaced compliance as the driving forces that shape behavior, and where the governing characteristic of working relationships is trust.

You don’t get there with Shock and Awe.

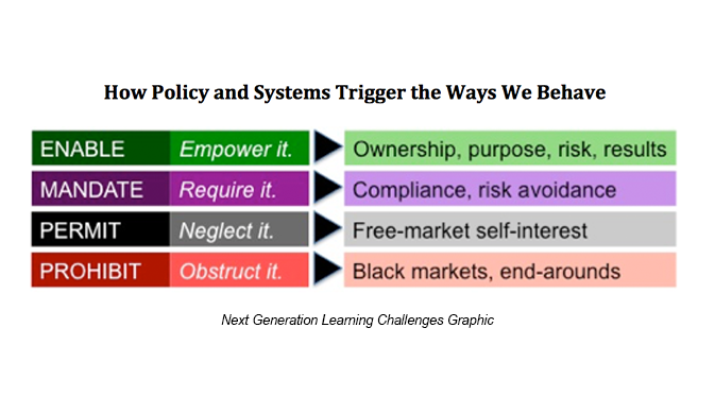

Instead of forcing behavior through compliance and extrinsic motivators, the new era will require ecosystems of policy, regulation, investment, and operating structure that enable, rather than dictate. That’s a non-intuitive blend in 21st-century America, and perhaps particularly in the world of K-12 education. Systems that… enable? What in the heck would that even look like?

Turns out that there’s an answer to that question. It looks like… New Hampshire.

Under New Hampshire’s PACE accountability system (the first statewide system granted a federal waiver from No Child Left Behind), districts and schools are now opting into using next-gen performance-based assessments, staked to much richer definitions of student success, on the basis of their readiness to do so. The state has already developed the nation’s most advanced policy environment, jettisoning industrial-age seat-time requirements on the K-12 side and the Carnegie Unit on the postsecondary side. New Hampshire educators are leading the work of redefining practice on all fronts: curriculum redesign, new roles for assessment, competency-based student progression, experiential learning. Postsecondary institutions such as Southern New Hampshire University and Keene and Granite State Colleges are reworking the ways new teachers are prepared and current teachers supported. The state’s early education community and its business/workforce councils are also an integral part of the effort.

New Hampshire is studying and incorporating a mix of ingredients from outside of the state (Common Core frameworks, Smarter Balanced assessments, NGLC’s MyWays, and more), but—true to its Live Free or Die heritage—the blending of these elements by such a rich cross-section of education and community leaders will make the Granite State’s approach entirely its own.

How Systemic Enabling Triggers Innovation

that Leads in Turn to Effective, Wider Adoption

Source: Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC)

In systems-enabling environments like the one New Hampshire is building for learner-centered education, policy empowers early-stage innovator/practitioners to lead the way in developing new, improved approaches (see adoption curve graphic, above). That work then paves the way for effective adoption more broadly by educators and communities across the state. Because learner-centered education depends on agency and ownership among all participants—adult and child alike—even the latest adopters won’t import 100% of the new learning models; they will customize or re-develop key elements to suit local contexts, build internal capacity, and “own the change.” The same dynamics could play out at the national level, where policy (NCLB waiver) allowed New Hampshire to innovate, and the revised NCLB—now renamed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)—will encourage other states to study and adapt elements of New Hampshire’s approach to suit their own contexts.

All of this is described in two timely reports, both prepared by the education group 2Revolutions in conjunction with state education leaders. To learn how New Hampshire got to where it is now, take a look at the New Hampshire Story of Transformation. To learn how it plans to fulfill its promise to become the nation’s exemplar in the seamless systemic enabling of richer, deeper learning from Kindergarten to career, take a look at Vision 2.0: New Hampshire Goes First. (NGLC funded the development of this plan and report through a grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.)

New Hampshire Goes First was released by the state DOE about six weeks ago.

- Five weeks ago, the state’s Virtual Learning Academy Charter School (VLACS) released its superlative new system for blended, experiential, competency-based learning that will serve students in every high school in the state—using the Motivis platform developed by NH-based College for America, the nation’s first accredited “direct assessment” competency-based postsecondary program. (Yes, you read that correctly: district high schools all across the state have a productive collaboration going with New Hampshire’s statewide virtual charter school.)

- Four weeks ago, at the annual conference of the Council of Chief State School Officers, hardly a plenary went by that did not reference New Hampshire as the harbinger of state systems design.

- Three weeks ago, funders and leaders from outside the state gathered at Parker Varney Elementary in Manchester, New Hampshire’s school of the year, to hear perspectives on the state’s top-down+bottom-up approach from enabled actors across the entire system: K-12 education (chief, superintendent, principal, teachers, charter, students), teacher colleges and universities, governor’s office, early childhood, business, non-profits. It was like seeing systemic enabling a phrase coined, in fact, by educator Bea McGarvey at this very meeting—come to life.

- One week ago, the US House of Representatives passed by a large bipartisan majority its redesign of No Child Left Behind, reflecting a move away from the outright federal mandates of NCLB and toward—well, we shall see, won’t we? It’s apparently all up to the states, now. The Senate passed its version earlier this week, also in bipartisan fashion, and the President signed it yesterday.

What will the new federal law enable? It’s too early to say. But every four years, the nation pays wildly outsized attention to one small New England state, with its four electoral votes. In 2016, the most earnest watchers may not be those consumed by the New Hampshire presidential primary. They’ll be those seeking to discover what the future of learning looks like, and the nature of the systems required to bring it about.

Editor's Note: This post originally appeared on Education Week on December 10, 2015. It has been updated to reflect ESSA's lightning-fast passage and the President's signing the bill into law.