Technology Tools

The Secret to Defeating the Status Quo in Education? Engage Faculty

Topics

Educators often take advantage of educational technologies as they make the shifts in instruction, teacher roles, and learning experiences that next gen learning requires. Technology should not lead the design of learning, but when educators use it to personalize and enrich learning, it has the potential to accelerate mastery of critical content and skills by all students.

Early engagement of faculty combined with ongoing training and resources is vital to the successful adoption of student success innovations.

“Moving a program elsewhere requires a careful retuning of the components and materials, such that all stakeholders in the new environment find it easier to follow this new model to success than to continue with current unsuccessful, but familiar, strategies."

—Project team member, Hybrid Labs at California State University, Northridge

Of the seven practices found to facilitate successful adoption of student success innovations in NGLC’s Building Blocks for College Completion grant program, the one I’m sharing with you today may seem the most obvious:

Cultivate the involvement of faculty with early engagement and ongoing training and resources.

In tech-enabled student success programs like the ones funded by NGLC, faculty are called upon to change their course pedagogy, redesign course content and activities, and learn skills to use new technology products and approaches, all with the goal of improving student learning and achievement. However, they often do not have the time or expertise to do so without support from their institution or the student success program’s provider.

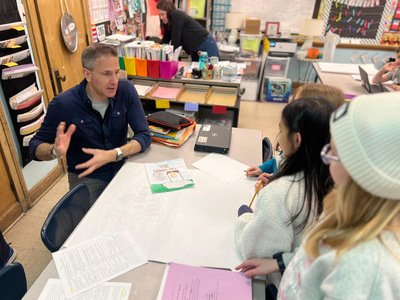

It turns out that projects with the highest significant positive effects featured active face-to-face contact between grant teams and instructors. Several gave attention to more systemic issues of change adoption, such as institutional culture and collaboration among faculty, according to SRI International, which evaluated the NGLC grants.

Grant recipients’ final grant reports suggested that their interventions would have not been successful if adoptions were formulaic; it was essential that instructors received the support they needed to decide how to best adopt and adapt the programs in their settings with their students.

Based on these results, I have three pieces of advice for you.

1. Engage faculty directly and early to encourage their participation and to reduce skepticism about the benefits of technology-enabled innovations.

In retrospect, Carnegie Learning project staff wished it had allocated more funding for travel to partner sites to hold a kick-off event for its Mathematics Fluency Data Collaborative. According to the project’s final report to NGLC, team members believed that if instructors had a closer relationship with program personnel and a more intimate knowledge of the pilot study, it would have mitigated much of the ambivalence they observed.

Conversely, from the project’s outset, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Classroom Salon (CLS) project team met with faculty to explore software, discuss pedagogy, and identify strategies on how to weave the CLS into their courses. Faculty contributed to software function and interface improvements and helped refine the CLS’s analytics tool over the summer.

2. Provide training to help faculty adopt and implement a student success innovation into their courses.

Whether the training was face-to-face or online, instructors implementing Building Blocks for College Completion innovations valued the training they received and those who participated in training were more positive about the innovation they were using and its benefits for students. (As part of its evaluation, SRI International conducted a survey of participating instructors.)

Many grantees implemented face-to-face training strategies like the SUNY Learning Network, which offered faculty workshops at their own and at their partner institutions to familiarize faculty with their offerings.

Some projects used technology-based solutions to train remote faculty, too. For example, the University of Central Florida offered a five-week MOOC to train faculty at the Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU) partner institutions about its Blended Learning Toolkit. In its first year, the MOOC drew over 200 participants from around the world. Over half came from non-AASCU institutions, creating an opportunity to expand the toolkit’s adoption to non-AASCU members.

3. Offer ongoing personal and tech-based resources to help faculty re-conceptualize their work.

Individual grantees approached this differently, perhaps according to project and cultural backdrops.

For example, the Bryn Mawr College Blending Learning STEM program team took a personal approach, identifying faculty innovators for its project and giving them the opportunities to showcase their experiences at three in-person workshops held at critical moments in time:

- One in the summer before implementation to familiarize their partners with the blended learning model

- One midway through the year to share experiences

- One at the academic year’s conclusion to present preliminary data analysis on the project’s pilot courses and to offer evidence that blended approaches work at liberal arts institutions

In addition, the Bryn Mawr team recognized that faculty reluctance could be tied to time-related startup costs, so they instituted course development stipends and assistance with an instructional technologist to build and assess courses. Bryn Mawr continues to support faculty adopting blended learning with its annual Blended Learning in the Liberal Arts conference.

Other grantees focused on technology-based tools and resources.

UCF designed its web-based Blended Learning Toolkit with an “out-of-the-box” mentality, which helped faculty members to re-conceptualize existing courses with blending learning elements. The Blending Learning Toolkit contains summaries of blended learning best practices; strategies, models, and course design principles; two OER prototype blended learning courses in composition and algebra; blended learning faculty development resources; and assessment and data collection protocols for blended learning.

OhioLink’s Scaffold to the Stars project offered faculty both technology-based and personal resources. The team indexed its Ohio Pro database of more than 460 math and statistics OER resources to specific outcomes; in addition they instituted a star rating system that translated into software rankings to help faculty with their resource selections. When the project team realized the selection of OER for their courses was still overwhelming, they hired a project librarian to help individual faculty members complete the selection process.

In the next post in this series, I look at how projects engaged students as designers and facilitators of the innovation, not just as learners.

This post is part of a series on technology-enabled innovations designed to promote student success. Read the first post and view the infographic summarizing the findings from NGLC’s first wave of grantmaking. All findings are drawn from an external evaluation conducted by SRI International as well as grant recipients' results and observations.