Building a Culture of Engagement through Student Agency

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

This school is learning that when students understand their goals, see their progress, and have a say in how they learn, engagement grows naturally.

Our middle school in the Bronx is always striving to be a place where students can take ownership of their own learning. Often in education, words such as “engagement” and “agency” are just overused buzzwords—but at the South Bronx Early College Academy (SBECA), we believe this mindset is crucial for adolescent learning. Our school has a rich Advisory program with student-centered discussions every day. Students choose a few of the courses they take each semester and one period a day is for Individualized Learning Time (ILT). This year, we are implementing a new structure for the Math ILT periods using Teach to One Roadmaps.

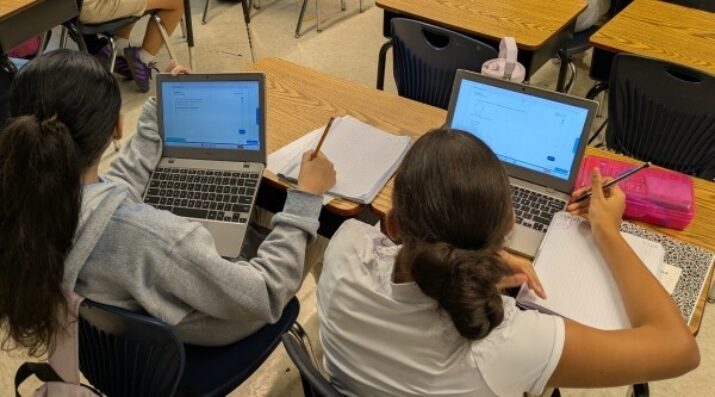

We are excited about the Teach to One Roadmaps implementation at SBECA because it aligns so smoothly with the vision of individualized learning. Unlike so many other online math programs, it is not merely “extra help” or “re-teaching.” Rather, it is truly individualized, with authentic choice for students, allowing students to monitor their own growth and holding them accountable for learning on their own. Teach to One Roadmaps allows students to move quickly or slowly, to learn individually or in groups, using videos or practice problems.

As we’ve launched this work, our teachers are focusing on a few key practices to help build the culture of ownership and agency while students work on Teach to One Roadmaps. This work is challenging and takes time for students to learn and develop more confidence and independence while using the program. We are trying to develop these skills thoughtfully, beginning with a few strategies at a time.

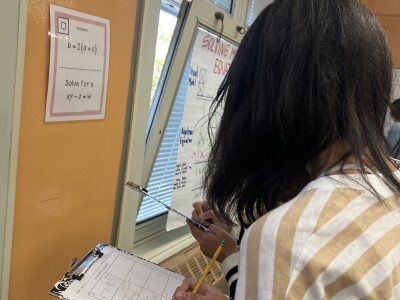

1. Where We Started: A Calm, Purposeful Environment

Middle school classrooms can be energetic—sometimes chaotic—spaces. So we began by intentionally creating a setting that feels different from the rest of the day.

We purchased simple headphones and started with quiet, independent learning so students could hear themselves think. That shift alone sent a message:

📌 This is time for focus.

📌 This is your work.

Although the headphones have helped with student behavior, the goal wasn’t silence—it was independence. Many students have never practiced learning without direct guidance, and establishing that expectation early helped build confidence and stamina. And students are feeling more confident watching the videos (sometimes more than once) until they understand.

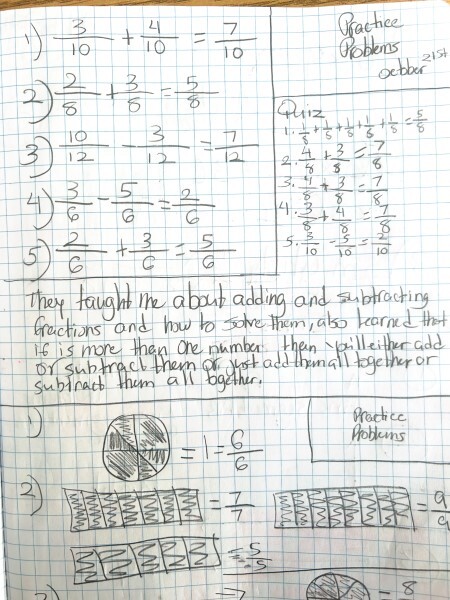

Using Notebooks to Support Deep Thinking and Problem-Solving

Early on (and in previous years), we noticed that with digital tools, it’s possible for students to move quickly without fully processing the content. We wanted to ensure the learning wasn’t just happening on screen—it was happening in their minds and (crucial for many learners) on paper.

To support that, we introduced notebooks with mandatory classroom routines. With some guidelines, teachers were encouraged to tailor the specific routines to their own classrooms. These are some of the requirements different teachers are implementing:

- Take notes on the video and explain a few things you learned about the topic

- Write three specific things you learned in the video

- Show your work for practice problems (or a specific number of the problems)

- Show all work for the five Skill Challenge problems and raise your hand to show the teacher when you complete the challenge

These notebooks now serve multiple purposes:

📌 A space for students to clarify and organize their thinking, and to “slow down” their thinking during the videos or practice

📌 Evidence of conceptual understanding (helping teachers identify gaps)

📌 A powerful tool for productive check-ins between teachers and students

As teachers circulate, they’re shifting from explaining content to asking open-ended questions such as:

- “Show me how you solved that.”

- “Explain this skill in two sentences.”

- “What resources will help you improve next time?”

Allowing space for productive struggle wasn’t easy at first—for adults or students—but these short questions build independence and help students develop the habit of thinking through challenges rather than immediately waiting for answers.

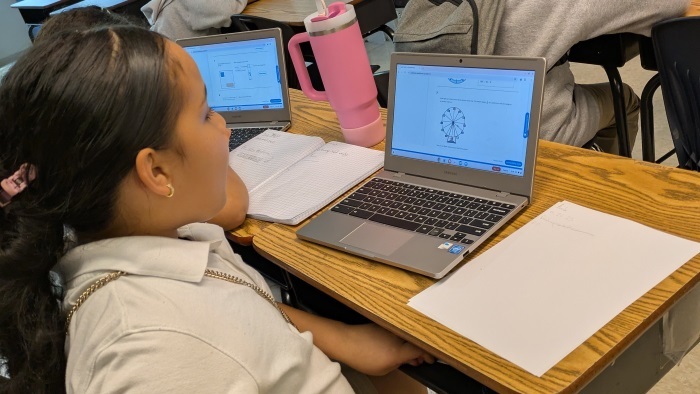

2. Where We Are Now: Empowering Students through Self-Monitoring and Goal Setting

At the beginning of the year, we focused on implementing and learning the new systems—using Teach to One Roadmaps (videos, practice problems, skill challenges), the room environment (headphones and independent learning), and deeper understanding (using notebooks). Now, in December, all teachers are conducting individualized check-ins with each student in their classes to review their data with them. Teachers show students how many skills are in their Roadmap, how many they passed in the diagnostic, how many they have completed since the diagnostic, and how many skills they completed each week.

One goal of these one-on-one check-ins is to ensure students are thinking about the year-long process of learning. Allowing students to reflect on the ways that they are using the Teach to One Roadmaps resources, and ways that they could be more successful. Teachers challenge students to think about ways to reach the goal—completing their Roadmap by spring 2026—and encourage them to ask for help when needed.

This will also provide an opportunity to remind students about their choices when using Teach to One Roadmaps. They can be thoughtful about choosing which skill to work on next, and how to best use their notes to develop deeper understanding. Using Teach to One Roadmaps at SBECA has noticeably increased motivation (compared to prior years using other platforms) because students now have ownership over their next step.

By reviewing the data with students, it also allows teachers to celebrate various types of student success. Some students lack confidence in math and were not very successful on the diagnostic—but will be celebrated for achieving two skills challenges per week while working on skills they are ready to learn. Others are sometimes bored in “easy” math classes and will be celebrated for moving onto more challenging skills ahead of their classmates. Regardless of where they began, students are encouraged to set a goal and track their progress throughout the year.

3. Still To Come: Build toward Collaboration, Gradually and Intentionally

We chose to begin with individual learning first so students could develop clarity and confidence before working with peers. That confidence doesn’t appear instantly—it’s built through routines that help students recognize their own progress and success.

For many students, confidence grew through:

- Successfully completing skills they selected for themselves

- Seeing their growth reflected in goal tracking

- Revisiting concepts independently when they struggled and trying again

- Documenting what they learned in their notebooks

- Discussing their thinking with a teacher through short, reflective check-ins

These moments—small but meaningful—have helped students internalize the idea that they can be successful learning math on their own, and that they know what strategies work best for them.

Next, with those foundations in place, we are planning to explore additional strategies:

- Peer partnerships

- Small skill-aligned groups

- Shared milestones and celebrations

This progression—from independence to collaboration—has felt natural and meaningful.

📌 First: Learning how to use Teach to One Roadmaps and creating the right environment for learning

📌 Second: Agency as an individual and developing the skills for independent learning

📌 Next: Building agency as part of a community that collaborates.

We’re just entering this next phase, and we’re excited to see how it evolves.

A Culture Built on Agency

If there’s one idea guiding this work, it’s this:

When students understand their goals, see their progress, and have a say in how they learn, engagement grows naturally.

We’re still learning and adjusting, but we’re already seeing students approach math with more confidence, curiosity, and ownership.

And this is just the beginning. As collaboration deepens and students begin working alongside peers toward shared milestones, we expect engagement—and agency—to continue evolving. I’m looking forward to sharing what happens next.

Credit, all photos: David Krulwich