Building Community

Making Teaching Sustainable

Topics

When educators design and create new schools, and live next gen learning themselves, they take the lead in growing next gen learning across the nation. Other educators don’t simply follow and adopt; next gen learning depends on personal and community agency—the will to own the change, fueled by the desire to learn from and with others. Networks and policy play important roles in enabling grassroots approaches to change.

Teaching will always be hard but there are steps school leaders can take to make teaching a more fulfilling and sustainable profession.

Let’s begin with the obvious: teaching is hard.

I think most folks can grasp that being intensely involved in young people’s lives requires vast energy, emotional intelligence, and patience. People who don’t teach are quick to say I could never when considering spending all day with large groups of, say, seventh graders.

That part is demanding, sure. But for most teachers I know, that’s what they signed up for. Contrary to some public portrayals, educators enjoy being around young people.

What makes teaching really hard is all of the other stuff. Seeing the proof of student growth and learning is gratifying, but grading is unimaginably time consuming. Complying with state and district mandates, being subject to an endless stream of professional development they didn’t ask for, and adapting to ever changing “reform” agendas that never seem to last all take time and energy, often with little benefit. And while teacher compensation is often discussed, an underrated challenge in the profession is its rigid, stagnant career ladder. There are few pathways to advancement for teachers who genuinely want to remain in the classroom, and the skill sets required to be an effective principal—along with the demands of a school administrator’s job—are very different from those of a teacher.

An overwhelming workload, a lack of recognition, and a stunted career trajectory: are we really surprised teachers are exiting the profession and fewer college graduates are opting into it?

As school leaders, some of these factors are outside our control. Contracts are collectively bargained and most districts do not seek school-level input on policy decisions. But there are steps we can take to make the work more fulfilling and sustainable.

Teaching will always be hard. I don’t hear any of my colleagues asking for it not to be. But it needs to be the right kind of hard.

First, we can buffer. The most obvious instances of buffering involve shielding teachers from unnecessary mandates and superfluous requirements. At the Workshop School, we are in constant dialogue with district leadership about which initiatives and requirements make sense for our model and which ones are either removed from our mission or redundant with work we are already doing. (Crosswalking work we already do with work we are being asked to do is another form of buffering.) Effective top-down buffering saves teachers time and preserves their energy for what matters.

Second, we can provide structure and support. The most gratifying part of teaching is the relationships you get to build with kids. Clear roles for staff, consistent expectations for students, and support for both provide a strong platform for relationship building. Conversely, relationship building is more difficult when teachers have to fill gaps (dean, social worker) outside of their defined role, as students try to decode different norms or expectations for each staff member.

Third, we can create psychologically safe work environments. It’s pretty common these days to hear platitudes about teachers being their “authentic selves” in the classroom. But just like the oversimplified call for “voice and choice” for students, we underestimate the level of trust and vulnerability that being your “authentic self” requires. If I am a teacher and I don’t believe my administrators respect me, am I really going to share my passions or interests? Similarly, if my relationships with students are fractured and there is a lack of trust, it is awfully hard to be personal or vulnerable.

Once we’ve done all of the above, we can tailor individual roles around teachers’ interests and strengths. This year, we launched Wednesday “passion projects” in which teachers pair up and teach a trimester-long project about something they are personally interested in. The projects are ungraded (though students can earn extra credit for being rockstars) and focus on themes like international travel, health and fitness, or the magic of plants. Students opt into the projects that interest them, allowing for new connections and relationships to form across grades.

Beyond what we do in the classroom, we can also be more creative in thinking about what teachers do outside of it. I know lots of folks who have every intention to continue teaching, but a blended role that lets them share their expertise with colleagues, contribute to the overall wellbeing of the school, or take on a new challenge can be both energizing and value-added for the organization. The role might even carry outside of the regular school day by offering teachers the chance to train or consult with other educators or organizations.

Finally, we can maximize autonomy where it’s most important. Over the years, we have experimented with a wide range of shared leadership and decision making models (and we continue to do so). One lesson I have learned from these efforts is that most teachers really don’t want to be involved in every decision. It’s time consuming and draining, and many of the decisions have little impact on their day to day work. What is most important is professional discretion and support for how they approach their work. For those in leadership roles there is often a tension here: schools need common goals, language, and systems, and part of a leader’s job is to uphold those once they are established. But that is the what of the work, not the how, which should be left to the folks who are in the classroom every day and supported in every way possible. At Workshop, we try to be as clear as possible about the skills we are trying to build and the performance expectations we have for students, and our “un-professional development” focuses heavily on staff sharing best practices and lessons learned in these areas. What we don’t do is tell teachers what a project should be about or how it should be organized. Instead, we offer any resources and support we can to make that project as amazing as possible.

Teaching will always be hard. I don’t hear any of my colleagues asking for it not to be. But it needs to be the right kind of hard. It should be creative and gratifying and dynamic. As leaders, we don’t control all of the variables that affect the quality of teachers’ professional lives, but we have enough influence that our decisions can mean the difference between sustainability and burnout, or between being a school that teachers want to join or a school they seek to leave.

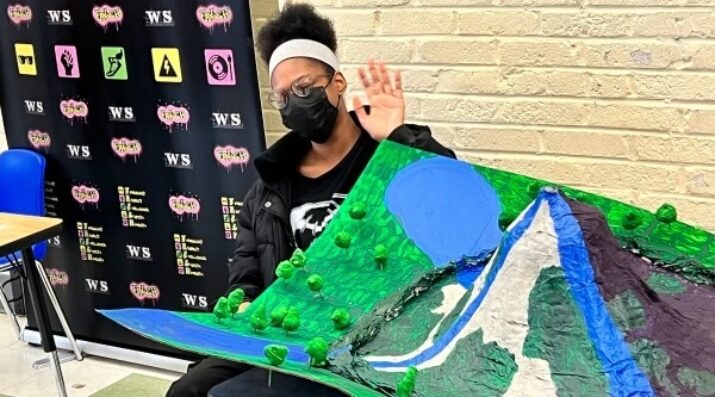

Image at top courtesy of Workshop School.