Next Gen Spaces for Whole Class Teaching and Learning

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

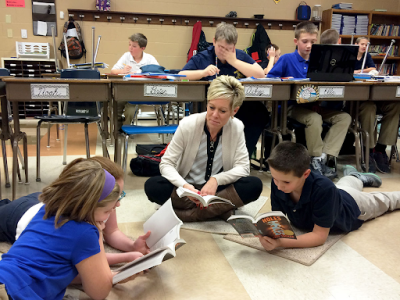

In large, flexible spaces for group learning, teachers balance the needs of individual students with the dynamics of the large group.

Innovations in teaching and learning have had little impact on modern space planning and school architecture. We know that students and teachers do better when they have variety, flexibility, and comfort in their environment. This series examines how next generation learning spaces impact the learning experience for students and their teachers. If you have the opportunity to design a new school building or renovate an existing building, or if you are interested in using space better in your school, this series can help ensure that the physical spaces in your building promote the skills students need to thrive and contribute to an ever-changing global society.

Large group learning can be highly effective when designed with strategies that encourage engagement, collaboration, and active participation. Teachers can overcome the challenges of large groups by incorporating diverse learning activities, using technology, and ensuring that the classroom environment is conducive to learning. However, for optimal success, it’s essential to balance the needs of the individual student with the dynamics of the large group.

Large group activities are either organized by student choice where learners determine the most appropriate learning space for their learning style; or they are facilitated by teachers to provide structured assemblies to encourage students to have conversations about their learning. Large group activities may include whole group collaborative learning, individual student work presentations, focused discussion and research, and break-out discussions. Consider this variety of uses when designing large group spaces by providing retractable seating to allow for open floor uses.

AI-generated image. Credit: Frolopiaton Palm on freepik

Key Strategies for Large Group Learning

Lecture-Based Instruction

A teacher delivers content to a large class, often using a combination of spoken words, visual aids (like slides), and demonstrations. This is common in subjects like history, science, and literature.

Pros: Efficient way to present information to a large audience. It can be an effective starting point for introducing new topics.

Challenges: Limited opportunity for individualized attention and interaction, and it may not engage students who prefer hands-on learning.

Interactive Activities

Class Discussions: While one teacher leads the class, students can actively participate in discussions. This method encourages critical thinking, allows students to share diverse perspectives, and fosters deeper understanding of the topic.

Polling and Q&A: Teachers can use technology or simple methods (like raising hands) to engage students in quick polls or Q&A sessions, ensuring that everyone is following along and thinking about the material.

Group Work: Even in large groups, teachers can have students break into smaller sub-groups for collaborative work, sharing their findings or ideas with the larger group afterward.

Collaborative Learning

Jigsaw Method: Students are divided into groups, each group focusing on one segment of a topic. Afterward, each group presents their findings to the rest of the class. This encourages teamwork and makes sure that everyone plays an active role in learning.

Think-Pair-Share: Students first think individually, then pair up with a partner to discuss their thoughts, and finally share with the larger group. This is an excellent way to ensure that everyone has a chance to process and contribute.

Technology Integration

Smartboards and Interactive Whiteboards: Using technology like smartboards in the classroom allows teachers to present dynamic, multimedia content to large groups. Interactive features help maintain student interest.

Audience Response Systems: Tools like clickers or online platforms allow teachers to pose questions and instantly collect feedback from large groups, keeping students engaged and gauging their understanding in real-time.

Flipped Classroom Approach

In a flipped classroom, students learn new content at home through videos, reading, or interactive online lessons. In class, they then engage in group activities, discussions, or problem-solving tasks to deepen their understanding.

Pros: It allows the teacher to spend more class time engaging with students through active learning rather than just delivering content. This method can be especially beneficial in large groups because it reduces the reliance on lecture-based teaching.

Challenges: The flipped classroom requires students to be self-motivated and disciplined about completing homework or pre-class assignments.

Differentiated Instruction

Even in large groups, teachers can differentiate the learning experience by offering various ways for students to access content, process information, and demonstrate understanding. For example, some students might prefer visual aids, while others might prefer verbal or hands-on experiences.

Techniques: Teachers can use tiered assignments, flexible grouping, or provide resources at varying levels to meet the diverse needs of the class.

Challenges: Managing differentiated instruction in a large group setting can be difficult, as it requires careful planning and organization.

Classroom Management

Strategies for Large Groups: Managing large groups requires clear expectations, routines, and engaging activities to keep students on task. Teachers may use signals, timers, or group roles to maintain structure and encourage focus.

Active Monitoring: Teachers must circulate among the students, checking in with different groups, offering support, and addressing any disruptions or issues that arise.

Peer Teaching and Mentoring

Older or more advanced students can help teach or mentor younger or less experienced peers. This method benefits both the "teacher" and the "learner" by reinforcing the material and building leadership and communication skills.

Peer teaching and mentoring promotes teamwork, boosts confidence, and allows for more personalized learning, even in large groups.

Credit: rawpixel.com on freepik

Benefits of Whole Class Learning

Cost-Effective: Large group settings allow teachers to reach more students without needing additional staff or resources.

Diverse Perspectives: In a large group, students are exposed to a variety of ideas and opinions, which can deepen their understanding and broaden their viewpoints.

Social Learning: Students can benefit from social interactions with peers, learning from one another’s experiences and ideas.

Credit: alrasyiqin on freepik

Challenges of Whole Class Learning

Limited Individual Attention: With so many students, it can be challenging for teachers to provide personalized support.

Engagement Issues: Some students might disengage if they feel lost in the crowd, or if the content doesn’t directly apply to them.

Classroom Management: In large groups, maintaining discipline and keeping students focused on the task can be difficult.

Learn More

See the whole series about next gen learning spaces.

Photo at top courtesy of Intrinsic Schools.