How Authentic School-Community Partnerships Drive Student Success

Topics

Today’s learners face a rapidly changing world that demands far different skills than were needed in the past. We also know much more about how student learning actually happens and what supports high-quality learning experiences. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Truly successful school communities actively address community challenges and expand opportunity through integrated, authentic support and strong relationships.

We all know the exciting rush of a new school year and the many preparations before the first day. Amidst this energy, a powerful way we can support our students and their families is by truly getting to know them, connecting with their unique stories, and seeing their potential. When we build these strong relationships right from the beginning and continue them throughout the year, we can proactively identify opportunities to ensure every child has the essential resources to thrive—from appropriate clothing and school supplies to a deep sense of belonging within our vibrant school community. Meeting these fundamental needs is key to unlocking a child's full ability to learn and succeed. Even seemingly small gestures, like ensuring a student starts their day with a nutritious breakfast, can make a profound difference, setting them on a positive educational journey from the very first bell.

At Distinctive Schools, our vision is to actively dismantle hurdles and uplift a child’s potential. We do this through our Community Hub model. At each of our campuses, we are reimagining schools as community centers of connection, care, and opportunity, led by our Community School Coordinators (CSC). We believe truly successful school communities can actively address community challenges and expand opportunity through integrated, authentic support rooted in strong relationship-building. It’s through these meaningful alliances and a profound understanding of our families’ needs—built on mutual trust and genuine connection—that our community hubs provide access to essential resources, uplift community voices, and offer consistent programming that wraps around students and their families year-round. This is how we ensure every student can thrive.

A successful school community thrives when it acts as a comprehensive support system. Our Community Hub Model is built on this premise, working to ensure a consistent, coherent experience across all our campuses, providing essential social-emotional and mental health support, out-of-school time opportunities, and support with basic needs. It takes more than a commitment to a comprehensive support system, though; to truly integrate with the neighborhoods we serve, it is critical to have that connector between the school and the outside community who is dedicated to building mutually beneficial and deeply authentic collaborations.

Meeting Foundational Needs through Personal Connections

Consider Jesus, our CSC at CICS West Belden. Understanding that foundational needs often precede academic success, Jesus spearheaded a large-scale Community Drive. Collecting and distributing donated resources—from Operation Warm clothing to Enchanted Backpack supplies and Colgate hygiene products—he ensures families have access to essential material needs. What truly drives this success is Jesus's commitment to genuine, personal relationship-building with community members and partners in the Belmont-Cragin neighborhood. He volunteers at partner events as a way of giving back, solidifying these personal connections, embracing an “all means all” spirit. This hands-on, relationship-driven approach means that when 40 families line up for his Community Drive opening, they are met with organized, caring support without question.

Supporting Families and Staff Alike with Partnership Support

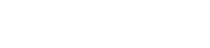

At CICS Loomis and CICS Longwood Elementary, CSC Tammy exemplifies how strong partnerships and deep knowledge of community needs can profoundly impact families and staff. Last year, Tammy secured a partnership with Enchanted Backpack, resulting in approximately $30,000 worth of donated items between the two schools. These donations included shoes, coats, school supplies, sports equipment, hygiene products, and even brand-new books. This partnership had a powerful ripple effect: teachers were relieved from out-of-pocket expenses for classroom supplies, and children's faces lit up with joy receiving new coats or toys for the holidays, removing financial barriers for both educators and families. Access to partner resources helped Tammy provide essential items to a student’s guardian who lost everything in a fire after having connected with the individual during a parent workshop.

Providing Language Opportunities to Support the Whole Community

Our commitment to holistic support also embraces adult learners. Dolores, CSC at CICS Prairie, recognized a significant need within her large Spanish-speaking community to address language access. Partnering with City Colleges of Chicago, last year she launched free ESL classes for families, with over 20 participants beginning—and many completing—the 96-hour program. Dolores’s personality and active presence in the Roseland community foster mutually beneficial ties with partner organizations. She volunteers for partner events and helps bring the Hispanic community’s perspective into broader conversations, even sitting on an advisory board for Chicago’s new red line subway extension after facilitating a focus group that included school families.

Fostering Belonging through Early Family-School Connections

Building belonging starts early and extends beyond academics by overcoming social divisions through intentional opportunities for connection. As demonstrated by Morganne, CSC at CICS Irving Park, she organizes "community playdates" and summer movie nights—events initiated by the school but typically family-led. These gatherings help new, current, and even prospective families connect with each other and the school team, building that sense of belonging before the school year even begins. This intentional outreach and programming transforms CICS Irving Park into a year-round "village"—a consistent network of resources and support, even during summer breaks. These events serve as safe, welcoming spaces where students and staff can connect outside formal classroom settings, showcasing how our administrators and teachers are also invested members of the community (with their own families attending events), fostering deeper, more genuine relationships that bridge the traditional school-community divide.

Our commitment to the Community Hub Model is a comprehensive, data-driven, and collaborative effort to elevate crucial connections. By fostering belonging, providing consistent resources, ensuring coherence across campuses, and prioritizing initiatives identified by our community, Distinctive Schools is fundamentally removing these barriers to learning. Through meaningful partnerships and dedicated relationship cultivation, we are fostering stronger school-community connections and uplifting access to high-quality, inclusive programs that support academic success, well-being, and civic engagement, truly creating a "village" where everyone can thrive. These stories represent the soul of our schools—spaces where partnerships are personal, voices are honored, and families are embraced as essential members of our learning community. As we launch a new school year, we carry forward this commitment: to meet every learner and family with open arms and meaningful support.

All photos courtesy of Distinctive Schools.