A Conversation about Grading and How It’s Good… for Gravel

Topics

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

In a wide ranging conversation, Carisa Corrow and Gary Chapin, of Educating for Good, dig deep into the harm done by traditional grading and ask, “Is it even possible to grade equitably?”

Carisa: On my most recent scroll through my socials, two posts happened to catch my eye. One was an invitation to join an equitable grading group, the other was a post by a well-regarded grading expert, who was talking about the next big shift to equitable grading practices. And I wondered, is equitable grading even possible?

As a practitioner, I know that right now in most of our current systems, we can do better than the hodgepodge of mathematical averages that may or may not be connected to learning goals. Like those 100 points I used to get each class if I covered my textbooks overnight in brown paper bags. (Now, I’m wondering if I can still remember how to do it?)

And as disconnected as that type of grading is, I also know it would be difficult in most communities to just pull the band-aid off and go cold turkey, no grading but narrative reporting connected to learning goals. Most will need baby steps.

Still, I wonder how much harm we will continue to do by devising and imagining these “better” grading practices, like giving a 50 rather than a 0. Will we ever achieve the actual goal?

Take police as an example. I would love to live in a world where we don't have police. No police. I mean honestly, isn’t that the actual world we all want to live in, a place where there's no need for police? Why not say the thing we want? Why are we talking about equitable grading at all? It’s an oxymoron... just like unbiased assessment… it’s impossible to achieve, so let’s just skip over the concept altogether.

Gary: This is the conundrum of our career. Equitable grading may not be possible (because grading is designed, literally, to create hierarchies), but more equitable grading is possible, certainly. Do we, as Educating for Good, help folks behave more equitably? I think we try.

It would be difficult to pull the band aid off because there are still things that schools need grades to do, and those things involve money, and they carry much importance because of that. I would be thrilled if we could have a conversation where we talk about all the things we ask of our grading system, and then figure out ethical—or, “for good”—ways of getting those things done.

More belief work needs to be happening. People aren’t holding onto grades because they think them necessary, but because they are convenient. An efficient way to do a rotten thing is still rotten.

You can see this when you hear folks say, “We want every kid to learn to high levels.” And yet, when every kid gets an A, it’s a problem.

Do we go along with the Atomic Habits (James Clear) doctrine that big change happens from a stack of small changes? There’s a lot of resistance to changing grading, a lot of friction. Are there small things we can change that will remove friction? Are there small things that will make, for example, narrative reporting or assessment as storytelling more likely to come into being?

And if there are, is that enough for us? Is it enough for Educating for Good?

Carisa: Yes, there are small things we can do, and we can't let folks get comfortable in the in-between. They need to see these more equitable shifts as a stepping stone to something drastically better. Otherwise we risk the continued inequity.

We have found this many times in our work with schools that are moving from conventional grading practices such as averages, 100-point grading scales, and letter grades to competency-based assessment practices. They are keeping two sets of records, one with the averages that so many “understand” and the other a competency score which is usually based on the averages.

I must put “understand” in quotes because conventional grading is all over the place, and while most folks can describe how averages work to give a grade, the way teachers arrive at that number is inconsistent, sometimes even within the same school.

I know we often address these inconsistencies with systems alignment including calibration exercises, which attempt to make things more equitable, AND I'm just stuck on folks getting stuck there.

To note, calibration regardless of the type of reporting—averages, competency score, or narrative—is an equity practice all schools should engage in.

Narrative reporting, student self-assessment, and storytelling already exist, even if only in a relatively few places in our vast ecosystem of educational institutions. I wonder what it would look like in five years, if we all acknowledged that grading systems exist, AND if we're going to have equity, we're going to need to abandon those systems altogether.

I’m helping to facilitate a School Change class in a high school. There are 16 students. At the beginning of their first big task, a podcast, we asked them to identify which competencies they thought they might demonstrate while doing the task. At nearly the halfway point, we had them choose which learning targets they think they demonstrated. Then they had to defend their rationale with at least one concrete example. One response, “This is really hard.” My response back, “Think of what your teachers have to do.”

Because students were asked to describe their learning based on a set of learning targets and those reflections were used in our assessment of them, we were able to achieve a more honest perspective of the learning. It is harder, it takes more time, and it's worthwhile.

It's not easy or quick, and this is where I think we, and our consultant and school change folks, need to push on schools. We should intentionally switch the word and concept of grading to assessment when we're talking about reporting student progress—a more equitable assessment process.

Gary: I love that story of your School Change class. It reminds me of the CBE grad classes I teach around assessment where we develop these amazing assessments; I convince them about the one point rubric; I try to push them toward narrative reporting and… they still have to give a traditional grade because of the system (i.e., grading policy, SIS parameters, insistence of the guidance department because of colleges). We do great work and feel great about how the kids do, but still feel thwarted.

This is why, years ago, I began to frame the change work of our teachers as civil disobedience. It wasn’t ideal—because civil disobedience implies long term success, but short term disappointment—but it was a story teachers could embrace in themselves. They knew they were doing the right thing and felt good about their methods and motives, but casting this as civil disobedience allowed them to feel—dare I say it—heroic.

This gets beyond the rightness of what we’re talking about—of course we think we’re right about grades, otherwise we’d be advocating something else—and more into our experience making change.

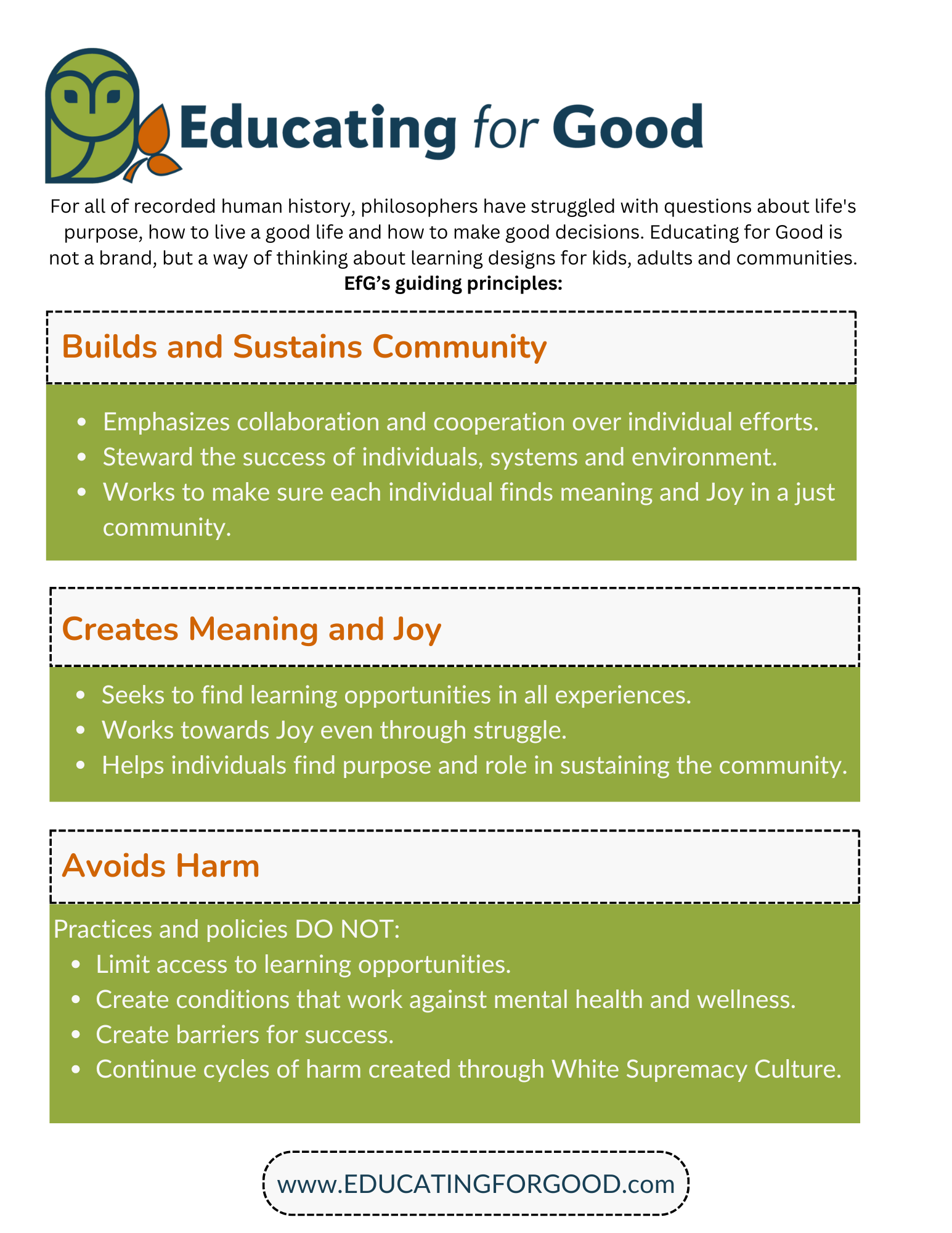

Carisa: Well, let’s not focus on what is right. Let’s focus on what is Good and how we generally have defined Educating for Good. Do grades work to Sustain the Community? Is there Joy and Meaning in grades and the grading process? Do grades Cause Harm?

I think grades could possibly be used to Sustain the Community if they weren’t used for competition. But, the reason why we even have grades in school is because of this compelling need to rank and sort humans and the things they produce. This is a pretty good summary from our friends over at Human Restoration Project.

I often use the analogy of maple syrup when talking about rubrics and grading. When we grade maple syrup, we are not deciding what is better or not better, like we do with student work. We’re actually determining how much processing it’s had. And it’s important to note that in the end, different people like different grades of syrup on their pancakes. And the same people might like different maple syrup on their pancakes than they do their ice cream or their snow. Different grades serve different purposes and tastes. To see how maple syrup is graded, check out my favorite video on the matter. By the way, the same is true for crushed rock, although I haven’t begun to understand that particular grading system.

I digress. We’d have to rethink the purpose and function of grades if they are in any way going to sustain a community for Good.

Our second “for Good” tenet is Joyful and Meaningful. Do grades fit the bill?

Gary: Excellent question. I can think of only one situation where grading is joyful, and that’s when a kid finds out that they’ve passed and, by the measure of the system (which they’ve internalized), succeeded. This feels like a pretty meager type of Joy.

While teaching, I never felt grading was joyful, though I agreed it was necessary—this was early days. But something about it left me feeling like I should take a shower. I remember spending a lot of time thinking about how I might alter the spreadsheet I used for grades (we didn’t have a grading program at the time). I thought grading was fine, if I could only get it right.

I never got it right. Grading was never fine, and I don’t think you could argue that anything about it was joyful.

But I also don’t think joy was on the list of things folks thought a grading process should bring, which is very strange because any genuine learning experience I’ve ever had, especially away from school, has been very joyful (not necessarily easy or pleasant, but, in the end, joyful).

As to whether it’s meaningful…

There are two senses in which you could use the word “meaningful.” The first is whether grades have “a meaning,” which they do, of course. They communicate information. They mean something.

The second is whether grades contribute to the meaning in our lives. Do they contribute something important to our kids and our lives that adds depth in an important way? When we say that a piece of literature is meaningful, or a piece of music, or an experience in the woods, or a class, or a learning experience—we are saying that thing made our lives more meaningful, that we connected with something which provided a revelation and cause for reflection and improvement. Possibly even peace and contentment or, let’s say it again, Joy.

As to the first form of “meaningful,” grades succeed, but only by the slightest margins. So little information is provided by grades that is useful to kids that the opportunity cost bound up in assigning, receiving, understanding, and reacting to grades means the entire prospect is a net loss.

And as to the second form of “meaningful,” the situation is even more dismal.

Even in the academic realm, where grades are supposedly most well suited, grades tend to obscure rather than illuminate. In any other area, i.e., all of the human and social areas on which the joy, happiness, and fulfillment in a kid's life depends, grades tell us nothing. And the importance we place on grades—our fetish for them—distracts us from so much that is genuinely meaningful.

There’s a book in the world of poetry, by John Ciardi, called How a Poem Means, which talks about the mechanisms poets use to make poetry that moves us, challenges us, deepens us, and humanizes us. Nothing in this book resembles the urge to quantify that schools are compelled to follow. Perhaps, rather than focusing so much on the science of learning, we need to invent a new inquiry: the poetics of learning.

Carisa: I like that, AND folks have been writing about the poetics of learning for decades, mostly in obscure philosophy journals.

The last part of our for Good philosophy is that whatever we do, we should Avoid Harm. And grading can't live up to that standard. It's kept kids out of opportunities. It's created unnatural competition and stress. It's been used to control, to discriminate, and it's distracted us from honest conversations about learning and growth.

So, grading is not for Good.

Gary: I agree. It’s good for gravel. It’s good for maple syrup. It’s not good for kids. As I indicated above—it feels like so long ago—if you’re grading you are sorting kids, not improving kids. Grading requires a curve of some sort, and it requires that some kids are at the bottom, and other kids are at the top. If you are grading, then you are behaving, inherently, as if you do NOT believe all kids can or should learn to high levels. Whatever you say you believe, you’re just shuffling the hierarchy for the next batch of kids.

Thanks to Judith Kurtz for the early read and suggestions.

Photo at top: An eighth grader presents her solutions for solving a human rights problem in the United States. Photo by Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages, CC BY-NC 4.0