Professional Learning

A Year in the Making: The Fourth Lesson My New Year's Resolution Taught Me about Next Gen Learning

Topics

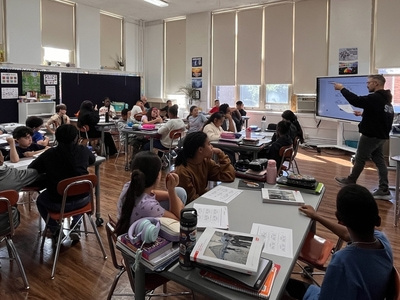

Educators are the lead learners in schools. If they are to enable powerful, authentic, deep learning among their students, they need to live that kind of learning and professional culture themselves. When everyone is part of that experiential through-line, that’s when next generation learning thrives.

When the environment and logistics don't support learning, it's hard to enjoy a learning experience. Even if it's a maker learning experience.

A few years ago, I decided to set fun New Year’s resolutions to prompt myself to make time for joyful things. It was in that spirit that I determined to take a creative class each month in 2017.

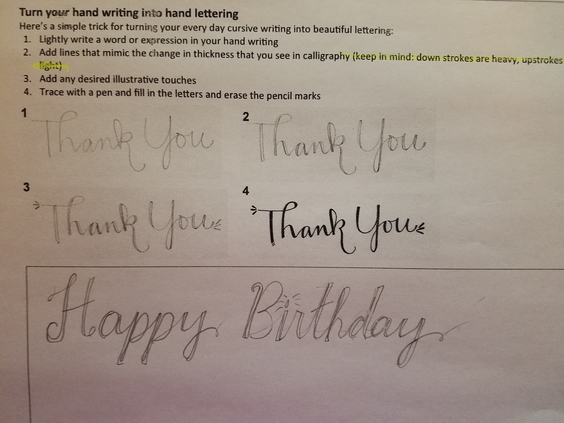

This is the fourth post in a series about my experiences implementing my resolution throughout last year. Unlike the three previous posts, this one describes my experience with a class that didn’t work out well. Reflecting on why it wasn’t as satisfying as my other courses, I came to understand how important the learning environment can be. Below, I share some insights that I gained through my creative hand lettering class, along with providing additional resources about using time and space to support learning effectively.

Lesson #4: The learning environment and logistics matter

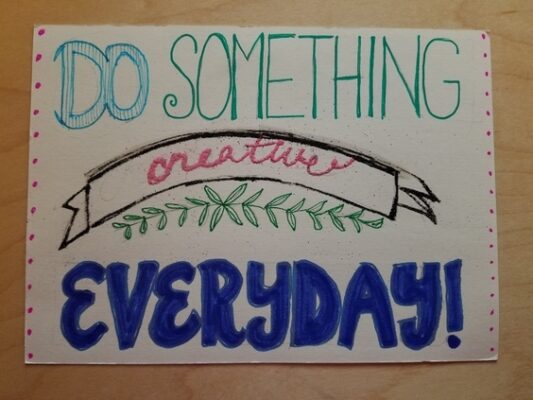

Lesson learned: June 2017, creative hand lettering

The majority of this blog series is dedicated to the lessons I learned from classes that I enjoyed. On the whole, I experienced a wide variety of high-quality making opportunities this year. Unlike the bird carving museum and mill settings I described in my previous post, there was one class I just didn’t like because the environment and logistics did not support my learning.

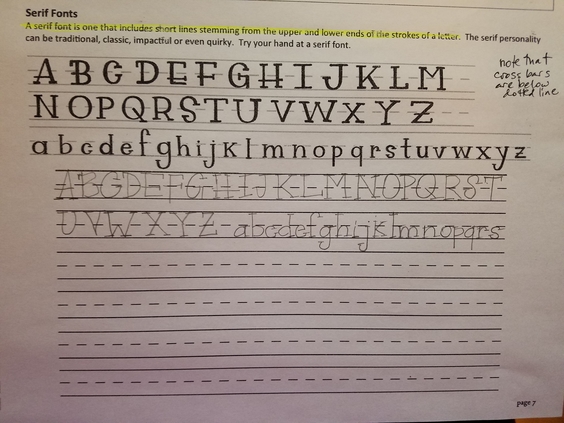

The class, on hand lettering, was held in a busy stationery store. The “classroom” was a big table in the middle of the store with metal stools gathered around it; disruptions abounded as customers shopped, cash registers beeped, and employees re-stocked shelves. When late students arrived, we had to pause the class and rearrange ourselves around the table. The fixed table area also didn’t really allow for interactions with students other than those immediately adjacent to me, and those felt stiff and formal because we were conscious of keeping our work within our allotted space. The cramped space didn’t foster experimentation even in the limited time allocated for that. During the period when we tried different materials, the teacher stood away from the table so individual students could bring questions to her, but this distance also meant that others could not hear the tips she imparted or contribute their own suggestions.

While the physical variables impeded my learning, lack of adequate time was also a factor. Although the teacher seemed well-versed in her content, the time allotted was too short for her to both instruct us in the basic procedures and allow us all to really explore the materials. During the short experimentation period, there was polite jockeying for materials and equipment as students grabbed what they needed and returned to their stools. I barely finished the small piece I was working on and felt rushed throughout our time. The instructor seemed to feel rushed as well, as if she was very focused on the content she was required to “get through” during our workshop (which I believe may be standard across other instructors and locations).

When I reflect on this class compared to others I took last year, the most noticeable difference was that we also didn’t have time to build a community with the teacher or our fellow students. Even with adult learners, a teacher’s subject-matter expertise alone is not enough to create a successful learning experience. In this case, challenges with time and space prevented cohesion within the group. Students who arrived late missed the minimal introductions period, so I didn’t have the chance to learn their names. One of the fun parts of a group class is the socializing that occurs while making, but we were so crunched for time that there was little friendly chatter. The lack of community was most obvious to me at the end of the class period, when there was no opportunity to share our work with others, and people just drifted away to shop for materials or leave the store for other activities.

Because I took so many different creative classes last year, I know that one session is not a referendum on hand lettering. However, a less experienced student might disengage from this craft altogether as a result of the learning environment. Let me be clear: I love this store and continue to enjoy shopping there for various making supplies. But a productive shopping environment and a productive learning environment are two different things.

Reflections and Insights

My transition in fall 2017 to my current role as Next Generation Learning Challenges’ (NGLC’s) Program Officer for our Mass IDEAS initiative also meant that I transitioned to a virtual work environment for the first time in my professional life. Now that I can work anywhere, I’ve been thinking a lot about where I learn best and when my K-12 learning had these characteristics.

For much of my formal education, I learned mostly at desks (and sometimes lab tables), in rows, with a teacher at the front of the room. Generally, we students had to be quiet, except when asking or answering questions, presenting, or participating in teacher-initiated group work. When I was a student, only music teachers played music in K-12 classrooms. With rare exceptions, deviations from this style of learning environment didn’t really happen for me until college; the few I can recall—writing and enacting skits in French class, labs at the beach in Oceanography—were in electives, not core courses. Core courses were serious, and serious learning was thought to require quiet voices and students in rows.

As I think about the hand lettering class, I know that the physical characteristics of that environment were problematic for me. The sound was the most obvious detractor; however, the harsh lighting, cramped work table, and uncomfortable seating also didn’t help me feel my most creative. As adults, most of us can describe the physical attributes that we like in our learning environments: classroom vs. coffee shop, music on or off, desk vs. cushy chair, alone or with others. There’s a whole productivity industry of planners, guides, and apps to help us map where and when we learn well, and track the settings, times of days, and other factors when we’re most productive at certain types of tasks. Why do we rarely ask students what environmental conditions would help them to learn best?

Often, I think, because their answers are likely to be “it depends”—on the student, the day, the task, the hour—and accommodating all of those variables is challenging. The environments most likely to support all students’ learning need to be personalized for different learning styles and flexible for current activities. What if one student wants to work standing up, and another is most focused while sitting on the floor? How can I facilitate them working together on a team project? And what if that plan works when they’re writing, but is ineffective when they’re engaged in a lab? Another student may have felt satisfied with the lettering class, for example, if she appreciated the disproportionate time on instruction that made me crave experimentation, felt comfortable in the space that restricted me, and could tune out the noise I registered as constant interruption. How do we support both that student and me in the same lettering class, plus all the other students present that day?

It requires knowing your students and advance planning—and an adaptive, elastic climate in the moment—to create a learning environment personalized for all students’ needs. Although developing these conditions takes more effort than offering one fixed way for students to learn, how can we do anything less if we want all students to be prepared for ongoing success in school, work, and life?

Want to learn more about creating environments that support a variety of different learning styles? Take a look at this article from EducationNext that describes an educator toolkit by Next Generation Learning Challenges and 2Revolutions on using space and time to improve students’ learning experiences; this post highlights six top tips from the toolkit. A recent piece about High Plains School describes in detail how one teacher developed the components of her classroom setting with input from students, one example of how Colorado’s Thompson School District is rethinking its learning spaces. Finally, this piece by Distinctive Schools in Chicago discusses the importance of providing time, space, and encouragement for adult learning, too!

Tip for crafting your own Year in the Making: Whether in a classroom, a shop, or at home, your making environment will set you up to either have a fun and productive learning experience or turn making into a chore. Do what I failed to do for the hand lettering course: ask in advance for details about the learning environment. How many people will be in the class? Where exactly will the instruction occur? How much time will we have to experiment with the materials? Is the class offered at different times of day, or different days of the week? If the answers don’t match how you learn best, seek out other options for learning the same craft virtually or in person.

Previous Posts in This Series

This post is part of a series about my experiences with creative classes during 2017. See below for my earlier posts.

- In my first post, I talked about how making provides a different type of learning than most traditional schools provide.

- In the second post, I reflected on the sense of accomplishment that comes with making.

- For my third post, I considered the many non-classroom locations that could enhance learning experiences.