Designing for Equity

Accountability, Equity and Personalization

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

San Diego State’s Joe Johnson explains how communities might embrace accountability in ways that help them work toward deeper, richer outcomes for all children.

Equity is a driving force behind NGLC’s investments in next gen schools and Regional Funds partners. It’s implicit in our shared goal of preparing every student for college, career, and a lifetime of learning. Lately, we’ve been discussing it more explicitly, and we’re finding a willingness to talk, reflect, and wrestle with diverse and shared understandings about equity matters—maybe even more willingness than we first thought.

As I wrote about in an earlier blog post, Margaret Angell, one of the NGLC Regional Funds partners at CityBridge Foundation in D.C., said about equity recently, “It’s not a part of the work. It is the work.” She meant it’s not an add on, something we attend to when the occasion arises, or when the annual performance data is released. It’s an everyday effort. Part of regular, ongoing conversations. So, how do you know when you’re effectively engaged in doing the work? What’s your vision of success? And, how do you maintain focus on the vision, the conversation, and the work?

To get additional perspective on the issue, I called a friend, former boss, and true expert on the topic, Dr. Joe Johnson, Executive Director of the National Center for Urban School Transformation (NCUST) and Dean of Urban Education at San Diego State University. He said, “There’s a thread that winds through your regional sites. It’s prominent nationally when it comes to equity. It’s how people “feel” about the results that different demographic groups of students are experiencing, and I don’t mean simply on standardized tests, but results across a wide range of issues.”

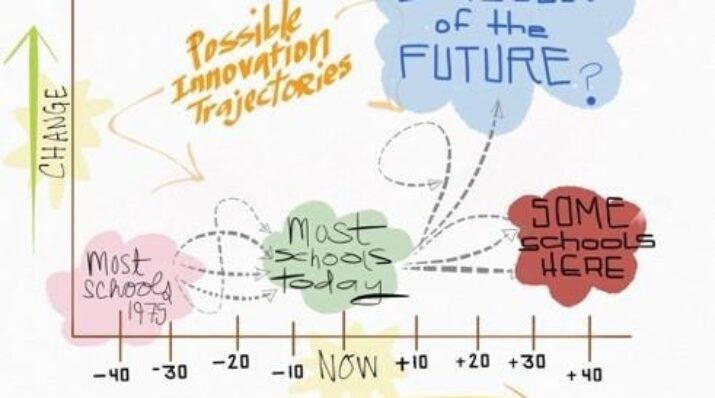

Since the reauthorization of ESEA, and amid unrealized results, I think some people are wondering, “Now what?” How do we move beyond No Child Left Behind, narrowly focused accountability measures, and draconian responses? If there is still a reason for accountability, then accountability for what? What should it look like now?

My hope is that communities find that a real (sense of) accountability doesn’t come in a federal or state mandate. My hope is that communities embrace a sense of accountability in ways that help them work toward deeper, richer outcomes for all children.

To illustrate these hopes, Dr. Johnson shared this story:

I recently visited two high-performing schools. Both serving very low income kids and communities. Both had good results and faced impressive challenges. The palpable difference I observed in the second school was inspiring. Those teachers were intensely reflective.... about everything they did… they were not willing to take any of their practices for granted as routine… they were so focused on college and getting their kids to a place of having a choice of colleges to attend. It was all happening in this nexus, the data room, which, get this... they called the “war room.” I wasn’t sure I liked that name.

I recently visited two high-performing schools. Both serving very low income kids and communities. Both had good results and faced impressive challenges. The palpable difference I observed in the second school was inspiring. Those teachers were intensely reflective.... about everything they did… they were not willing to take any of their practices for granted as routine… they were so focused on college and getting their kids to a place of having a choice of colleges to attend. It was all happening in this nexus, the data room, which, get this... they called the “war room.” I wasn’t sure I liked that name.

I’ve seen these data rooms before. They’re often required by some district policy. They display static data, maybe where kids scores are compared to the state average on end of course (EOC) assessments. It’s posted on a wall like you might hang art in a museum. The room is often locked (laughs). It’s something to show district administrators and visitors that yes, we care about results.

In the war room of the second school (which was not locked and actually buzzed with teacher interaction), I saw data about how students were performing on the EOC exam, how they were doing on the assessment used to access college credit early, and progress toward SAT performance (recall the goal of attending a college of the student’s choice). There were notes on every student. Notes about what kids needed to learn and master; what kinds of support and what kinds of issues existed at home; who needed to be engaged with a parent to support the kid through the current difficulty. The war room was a place of detailed planning for each student’s success.

I just had to ask, what is with that name? The principal said, “We are in battle for each child and we can’t let ourselves be comfortable with their results…. What we do or don’t do will make all the difference in the lives of these kids.” Woah! That’s the spirit with which they engage in the work. Despite the fact they were achieving results that surpassed other schools, and effectively serving low-income and ESL students—they were still in a battle for each and every child. Every decision was filtered through this lens: how they work together, their decisions about how they use technology, and how they promote extracurricular connections.

It was a palpable sense of ownership and accountability. You have to be invested enough to have feelings. The conversations in that school demonstrated how well these kids are personally known and cared for…. The principal would ask: Who has been to see the parent? How is that issue influencing the student’s behavior? What do you think we need to do? (The conversation co-created a picture and a call to action)...So, what’s our plan for doing that?

This is what it looks like when you take responsibility to not just look at scores and grades and standards but to focus on kids, and lives, and the challenges that they encounter. It was very powerfully personal. This is what each community needs to decide for themselves.

The policy is just a tool. Good leaders can use it to mobilize and catalyze change but without it, good leaders will find a way to do that anyway. How do we nurture and support a positive transformational culture that will influence real substantive change across a wide array of variables for all kids? That’s still our challenge. A real sense of accountability needs to emerge in these local conversations. That’s how it’s always been and likely will continue to be.