The Boundless Potential of Curiosity, Caring & Doing: More Dispatches from Agastya

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Education that arises out of curiosity, caring, and doing nurtures and unleashes the gifts of children and the wisdom of teachers.

This morning, two cows wandered onto the campus followed by a trail of yellow and black butterflies. When you are surrounded by beauty, then the beauty that lives inside you starts to emerge, without effort, like meeting a long lost friend. I understood instinctually why I needed to come to Agastya in Bangalore, India, but it wasn't until I arrived here that I discovered my role. Although I am a scholar in residence, my real job here—eyes and ears open, iphone, pen and notebook in hand—is a story-catcher in residence. Because Agastya’s stories need to be told. And I anointed myself as one of its tellers.

After four decades as an educator and teacher, often feeling like a chaser of windmills, a slayer of dragons, and a firefighter — I chose to leave the comforts of my New York home to embark on this remote place called Agastya. I came here hoping to find and retrieve something public education (as we know it) has long misplaced. Not a method nor a system. Nor a proof of concept. But a world view grounded in the immense potential of learners and teachers. I wanted something more than grandiose theories. Or eloquent words in the books of those who I admire. I sought to experience an approach that understood education not as control, compliance, and performance. I wanted to experience education as a continuous unfolding of the boundless intelligence of children to understand, make sense of, and contribute to the world. I needed to be reminded that this too could happen.

I shared my first impressions of Agastya in my first dispatch of Moving Mountains with Wonder, Joy, and Curiosity. Over the course of the last month and a half, I experienced how routines can be suspended and replaced by new ones. I've not tasted meat, fish, or alcohol. I do my headstands on the cold marble floor and find enough space in my room for yoga. Home, like the movement of water, has a way of accommodating itself to wherever you find yourself. We have this inimitable ability, like water that navigates around stones and roots and trees, to be fluid and invent home wherever we are.

Most people here, including the visiting students and teachers, speak at least three languages, not including English. I have no Telugu or Kannada or Malayalam. But we understand each other. There is a sense of solicitude here that I have not experienced since I was a boy surrounded by my extended family. The first thing the staff ask me when I encounter them is, “Have you had breakfast sir?” Village kids stare at me with self-conscious giggles. I work at containing my annoyance. I am white-skinned and that is undeniable. And the visiting teachers want to take photos with me, as if I am a rock star.

So far I’ve taught two workshops on Agastya’s four principles: Curiosity, Creativity, Confidence, and Care. And I’ve written and delivered a preliminary report of my observations, wonderings, and suggestions to cluster leads and to the organization’s board.

I do not want this to be a one off. I want it to be a “from now on.” I’ve come 8,000 miles to rediscover what matters.

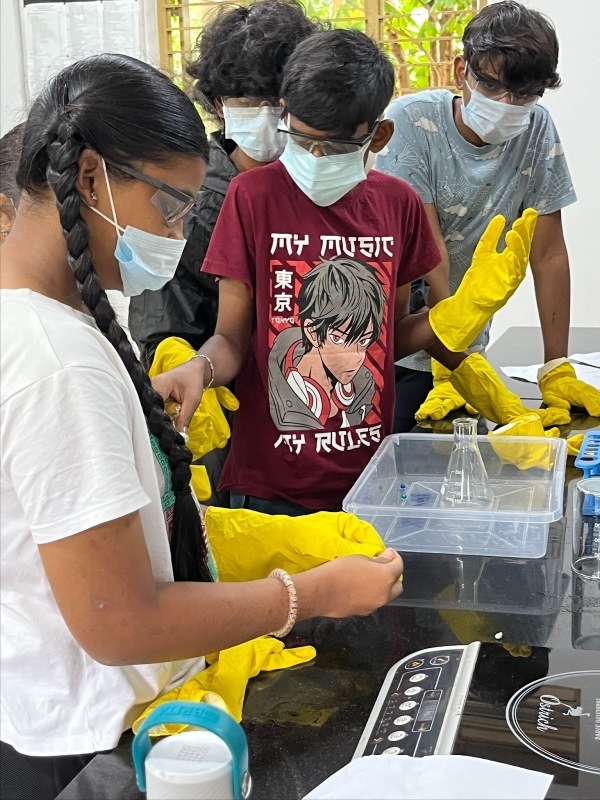

For one week I shadowed a group of teachers from the north east of India who were here to take a newly designed workshop on ecology. The local government of their state has made eco clubs mandatory. They have come here to find ways to make that meaningful for their students. And most of all, for themselves. The focus has been on how to raise ecological awareness in children through experiences and exposure to their natural habitats along with practical ways they can practice climate-based solutions. I am reminded of a Rachel Carson quote: “We need to cultivate an emotional response to the living world. [Children] should first become acquainted with the true meaning of subject matter through observing the lives of creatures in their true relation to each other and to their environment.” True to Agastya’s adherence to experiential and hands-on learning, a methodology of questioning is inserted into all aspects of their five days. The premise: If you are going to teach this way you must experience it yourself.

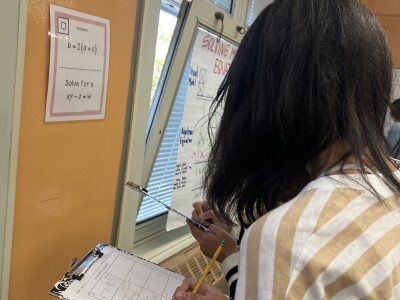

On day one after a conversation about nature and creating an idea web visualizing their thoughts, a day of fieldwork unfolds. Divided into teams of four, clipboards with worksheets in hand, their morning task is to collect evidence of biotic and abiotic elements in the immediate environment. Like children at camp for the first time, they spread out with the vigilance of biologists and an almost childlike sense of glee observing, identifying, and collecting samples of soil organisms, tree bark, diversity, flora, and fauna. Later that afternoon, each group presents their findings while sharing ways they could integrate such activities back in their schools. The instructors stress developing skills of observation and paying attention. The mantra today: If we can change perception, we can change behavior.

On another day, this group of teachers takes an early morning field trip to a nearby lake. Over the course of two hours, with worksheets, clipboards, strainers, and test tubes in hand, teachers wade into the water or stand at the shore line calling out instructions and data as they collect samples and test the pH levels, turbidity, salinity, and the existence of microorganisms. When they return to the auditorium each group shares their findings and experiences, responding to questions from the facilitators and their peers, how they could be transferring what they have learned to their schools with their children. It is all centered in making connections and not merely collecting data. Letting curiosity and questions guide learning.

Agastya’s epistemology, captured in Aah, Aha, and Ha-Ha is further solidified with this pedagogical mantra for shifting practice:

—From Saying Yes to Why

—From Looking to Observing

—From Being Passive to Learning to Explore

—From Being Textbook-Bound to Hands-On

—From Fear to Confidence

After a week observing this ecology workshop, the symmetry between word and action and mission and vision is transparent. The concepts and practices of hands-on, experiential, and project-based learning, now combined with design thinking, is not jargon or fluff at Agastya. The framework and practices support everything that happens here, from how children approach problems to the ways the arts are integrated in most inquiries.

When I ask children from government schools what makes coming here special (with the help of an interpreter), the refrain is constant: “Because sir, here we have so many models and resources. You don’t have to just read about the brain in a text book, you can use your hands and touch all the parts. You get to do learning and not just read about things. Here it is fun. We get to work with our classmates. And the teachers here are kind. There is no fear.” On the other hand, when describing their experience in government schools, they exhale like the taste of bitter medicine: “Textbooks. Tests. Copying from the board. Stern teachers who have no patience for our questions.”

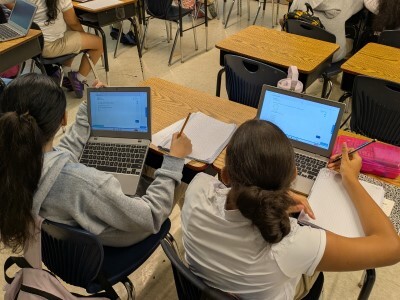

Listen to a few students from a local independent school in Bangalore share their perceptions about their experience at Agastya.

Would it be worthwhile for teachers to come here? Why?

Here, the students are the teachers.

How does learning, surrounded by the natural world, make you feel?

Something most tender and beautiful occurred at last Friday's shuddhi meeting. A young man was attending his last meeting. For financial reasons he was moving on to better support his family as an IT technician. He was with Agastya for seven years. Beginning as a student visiting from a local village. Then as a volunteer. Eventually as an ignitor in the garden (for which he interviewed three times, persisting after he was rejected his first two tries). As we go round the circle where everyone shares their plan or update for the day, he is visibly struggling. Each word followed by long pauses trying to compose himself. When he can no longer speak without crying, he excuses himself to go outside. As if by reflex,nearly half the assembled cluster leaders follow him outside in displays of empathy and care. When he is able to return, a black bag full of guavas are distributed to everyone. It is a moment of unabated solidarity suffused with the sweet fragrance of guava.

What We Can Learn from Agastya

Despite obvious differences of context and culture, Agastya is reminding me of educating without labels. Educating without fixing children. It represents what can happen when the natural gifts of all children and the wisdom and insight of teachers are nurtured, unleashed, and unfettered. What we can take from Agastya is counter to being “in the trenches” or subject to lock down drills, or “covering curriculum.” Nor is it about simply transplanting one model wholesale onto another. The profound value of Agastya emanates from an understanding of what expectations and beliefs we have in children, and the kinds of environments we create for learning to happen. It is founded on relationships of regard and caring. It draws on the natural inclination of children to learn from other children. It believes in the value of play not as “recess” but an integral part of how we learn. It respects the immense power of the imagination and storytelling. It practices an education that arises out of an ecology of curiosity, creativity, questioning, and doing. It views the continuous evolving of teachers not as training but ongoing professional and personal growth. And perhaps above all else, in the words of the Cuban poet and educator José Martí, it views teaching “as an act of infinite love.”

Questions to Ask Ourselves

I came to Agastya not seeking some kind of exotic experience. Or a picturesque vacation to memorialize in photographs. And I will leave here with questions addressed directly to the system we call public education: Can we make our schools epicenters of community, of belonging, and of well being? Can hope replace competition? Can care supersede performance? Can agency be prioritized over compliance? Can creativity (in all its guises) preempt test scores?

We don’t need to travel 8,000 miles to find out. The answers are to be found amongst us. We don’t need to be uncritically bound to a fractured system. Or wallow in structures and practices that are void of imagination. We just need to trust ourselves as discerning, critically minded, and restless educators. Those with the audacity to believe that hope and change, like an endangered species, can be restored and brought to a state of flourishment.

Read David's first dispatch: Moving Mountains with Wonder, Joy, and Curiosity: Dispatches from Agastya

All photos courtesy of the author.