Amplify, Hospice, and Create: How Schools Should Spend the Money from the American Rescue Plan Act

Topics

Next generation learning is all about everyone in the system—from students through teachers to policymakers—taking charge of their own learning, development, and work. That doesn’t happen by forcing change through mandates and compliance. It happens by creating the environment and the equity of opportunity for everyone in the system to do their best possible work.

With American Rescue Plan Act funds, schools and districts can create three years of awesome and incredible experiences for their students, at a scale that we may never see again.

The American Rescue Plan Act offers a one-time $123 billion infusion of money into the nation’s schools. How should that money be spent?

As always, it starts with purpose. What are we trying to accomplish and why? There has been a lot of talk about “getting back to normal,” but this ignores that what we call normal was not working for many students. When we have run focus groups with students, asking what they want adults to know about what they need for next year, intriguingly many of their answers are not about the pandemic, but rather long-standing issues that exist in school. They talk about learning things that matter and connect to their lives, having some agency over their learning, and being seen, known, and heard by the adults in their building. From that perspective, this money provides a significant opportunity to make some changes in schools—to create a new normal that was much better than the one we left behind.

At the same time, there are also some very pragmatic considerations that need to be attended to. These are one-time funds, which need to be spent within three years. That raises the significant question of how best to spend short-term funds to achieve a longer-term result. The old cliché that any long journey begins with a single step also still applies—even if the goal is transformation, we need to meet both students and adults where they are. So, what to do?

Take Stock and Set Direction

The first step is to take stock of local conditions. The impact of the pandemic has varied greatly across neighborhoods and communities; it is very much not a one size fits all situation. While “learning loss” has gotten all the attention, the range of different kinds of needs is great: some students need mental health support, some need chances to reconnect with friends and teachers, some have lost out on internships or out of school opportunities, and some may need more academic support. Until you have a clear sense of what the big clumps of need are in your community, it’s difficult to know how to spend the money.

A related idea is to develop some guiding principles for how to spend the money before deciding how to spend it. These principles can be developed transparently, and in concert with faculty, students, and community members. Examples of guiding principles are equity—money goes to those who need it most—or innovation—new money shouldn’t be used simply to support existing programs but should be an opportunity to develop something new. Co-developing these guiding principles ahead of time helps everyone work more collaboratively rather than simply advocating for things that support their own agenda. Such an approach will increase coherence and help avoid the temptation of buying shiny new things. It also creates an opportunity to build meaningful community involvement in educational decision-making, as opposed to the surface level consultations which are often the norm.

While exactly what to choose depends on the priorities of local communities, we would put in a plug to think expansively about the possibilities. Students have not just missed out on some content, they have essentially missed a year of their childhood. Thus we suggest that any response be broad-ranging and not myopic.

Amplify, Hospice, Create

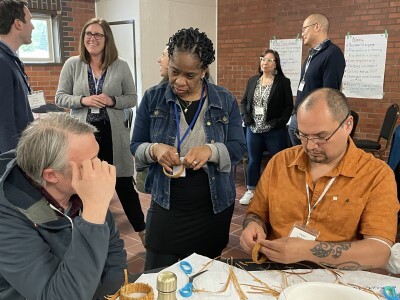

We have been running an activity with schools and districts called “amplify, hospice, and create.” The pandemic has massively disrupted school, which means that teachers, students, and schools have, out of necessity, found new ways of doing things. These range from large things, like mounting school online, to small things, like adding in an extra conversation with students and their families at the beginning of the year. Amplify, hospice, create is an exercise that allows you to think about three things to tap into the best of this year post-pandemic: what you want to keep, what you want to let go of to create space, and what new things you need. Some questions you could ask yourself are:

- What are some things that you want to amplify from this year?

- What do you want to hospice? What is no one asking to return to? What are you willing to let go of to create space for the new thing?

- What do you want to create? What new things do you want to make?

Amplify, hospice, create is a way to build upon what is naturally bubbling up out of this year and use that energy to create change. While we think of change as something that is really hard, there may also be some easy wins—it may turn out that everyone would prefer to take some meetings over Zoom.

The fact that there is money available creates opportunities to accelerate this process. School and district leaders can run this exercise with their teachers, students, and communities, and they will then be able to use some of the money to accelerate the emerging priorities. Because these ideas both are generated from the ground and grow out of what people are already experiencing as good, they are more likely to stick and be sustained.

Support More Radical Innovation in Pockets

When there is new money on the table, there is a real opportunity for genuine innovation. Much of what passes for “innovation” in education—shifting students to devices, letting students vary the pace of learning but not its content—doesn’t actually significantly change the students’ experience. Survey data consistently show that the longer students are in school the less engaged that they are, and this might be a real opportunity to change that.

The possibilities are endless. Many of them likely would involve moving away from the traditional “grammar of schooling” and creating opportunities for students to have more choice, do more relevant work, and connect more with institutions beyond the school.

One area that is ripe for rethinking is time. American teachers have among the most contact hours with students in the world—1,100 for high school teachers compared to fewer than 600 for teachers in Japan. Almost all of the world leaders make different choices than we do about time—using more time to plan and collaborate so that the hours with students can really count. We can’t do anything that is substantially different without changing how time is allocated. Tom Hatch’s new book reports that in Estonia, much of the academic learning happens in a more concentrated way in the morning, which allows students to choose a “hobby school” where they can choose to learn more about a particular interest in the afternoon. In Jason’s previous district, Jefferson County, Colorado, in the spring of 2020, Jason decided to hold one day for teachers to plan and students to catch-up on their work, which enabled a kind of teacher collaboration that is not possible during the school day.

This is also a good time to think hard about building connections with community institutions. Every community also has a unique set of capacities and strengths for addressing the needs of their students and families. These range from nonprofits, other governmental entities, higher education, businesses that support students and families, and faith-based systems. Using this money to create strong relationships with those organizations may well lead to relationships and partnerships that extend well beyond these one-time American Rescue Plan funds.

Invest in Things That Will Pay Back Over Time

Districts also should consider investing in things that will pay themselves back over time. The best investment you can make is in your own people—via coaching and other professional learning opportunities—which will increase the capacity of your school or district in future years or months. While it will be tempting to hire new people or buy new programs, those are not long-term investments. While it is not sexy, growing the skills of your people is almost always your best long-term strategy, because doing so in turn expands the capacity of your organization going forward.

Conversely, local leaders should avoid investing in anything that can feel like a “cut” if it is not renewed. This is especially true if you hire staff from the funds. When the funding ceases then those staff members will need to be let go, which will feel like a reduction rather than just a return to previous staffing levels. Every expenditure must be looked at for what happens when the funds run out. Is there a planned reduction of the activity once the funding ends, is the effort something that can be easily turned off or stopped when the funds run out, or is there a solid plan for funding the effort going forward?

Buying educational technology can be similarly problematic. Student devices are going to be part of our educational system going forward, but they also have ongoing maintenance and replacement costs which are not sustainable if they aren’t part of the regular budget. The same can be said for purchasing instructional programs or systems in which staff and students invest their time learning and using. Having to turn these systems off is an avoidable disruption.

Get Proximate

Bryan Stevenson, in his work on racial justice organizing, suggests that true change requires people to “get proximate” to the problem they are trying to address. As Stevenson writes, “You cannot be an effective problem-solver from a distance. There are details and nuances to problems that you will miss unless you are close enough to observe those details.” Stevenson’s argument echoes the Catholic Church’s principle of subsidiarity—namely that decisions should be made at the closest point to the ground that they can be.

For the American Rescue Plan money, we recommend that districts reserve a good portion of these funds to go directly to schools and classrooms. Principals, teachers, and school level staff will have the best insights into the problems their students and families face; providing flexible funds for them to solve those problems will be dollars well spent. Schools would do well to include students and families in their decisions around where dollars would do the most good as well. The closer to the ground these decisions are made the more likely they are to capture the imagination and build on the passion of students and teachers. Small amounts of “seed funding” made available for groups of students and teachers to apply for can capitalize on the passion and creativity of these groups. They will find amazing ways to stretch the dollars.

Students have missed out on so much during the pandemic in terms of quality of life and educational experiences. These funds present an opportunity for schools and districts to create three years of awesome and incredible experiences for their students and at a scale that we may never see again in our lifetimes. Schools and districts can create lasting and meaningful learning memories for students that will leave a positive imprint for a lifetime. With the support of communities and input from staff, students, and families, the experiences we create can be less about “learning loss” and more about gaining joy.

Photo at top courtesy of NGLC.

The authors: Jal Mehta, Rod Allen, and Jason Glass