Technology Tools

Can We Ensure Success for At-Risk Students?

Topics

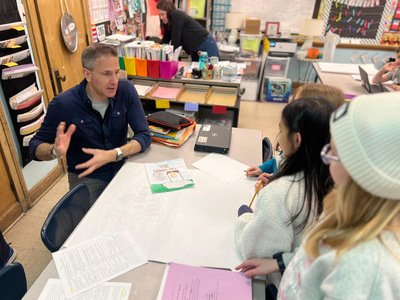

Educators often take advantage of educational technologies as they make the shifts in instruction, teacher roles, and learning experiences that next gen learning requires. Technology should not lead the design of learning, but when educators use it to personalize and enrich learning, it has the potential to accelerate mastery of critical content and skills by all students.

‘Rich kids graduate; poor and working-class kids don’t.’ Find out how a 30-minute learning module is helping one university to close the graduation gap.

At $75 million, the federal government’s First in the World grant competition (see my coverage of it from last week) to improve college completion rates is HUGE, but we don’t always have to go big to see big changes. Even small, low-cost efforts can help many students get to graduation.

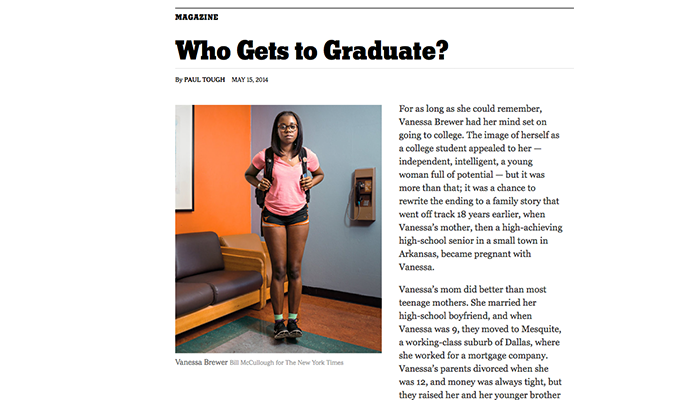

Paul Tough tells an emotionally and intellectually compelling story about one of those small efforts with big gains in his recent piece in the New York Times Magazine, Who Gets to Graduate?

First, Tough offers a humanizing perspective of the income-based achievement gap in college completion:

To put it in blunt terms: Rich kids graduate; poor and working-class kids don’t. Or to put it more statistically: About a quarter of college freshmen born into the bottom half of the income distribution will manage to collect a bachelor’s degree by age 24, while almost 90 percent of freshmen born into families in the top income quartile will go on to finish their degree.

Other writers might stop there and simply lament the state of inequality in college degrees. But Tough just continues to dig deeper. He debunks ability as the reason why rich students get to the end goal and poor students don’t. He underscores the effect of college “fit” (recognizing that, in fact, students do better at more selective colleges) and acknowledges the impact of what it’s like to be the first in your family to attend college.

One Institution’s Solution

In a truly nuanced profile, and using efforts at the University of Texas at Austin as an example, Tough details how paying attention to students’ mindsets—their doubts, misconceptions, fears, and resilience—can actually help more students graduate. UT Austin is using predictive analytics to first identify the students at highest risk of not completing college, and then providing those students with highly structured, intensive programs that recognize their scholarly abilities—their potential for success.

Tough then goes on to describe how UT Austin is also using targeted messaging to address ALL students’ doubts—doubts about belonging in college and doubts about their academic ability—especially after they experience a setback like a poor grade on an exam. Provided as part of an online pre-orientation for incoming first year students, UT Austin’s 30-minute module had pretty profound results in reducing the gap in advantaged versus disadvantaged students at least by one measure—the percent of students completing 12 credits in their first semester at the university—essentially cutting the gap in half. Not bad for 30 minutes.

What else could we accomplish in 30 minutes that could completely change a student’s trajectory?