A Case Study in Community Engagement: Grappling with Challenges to Standards-Based Grades

Topics

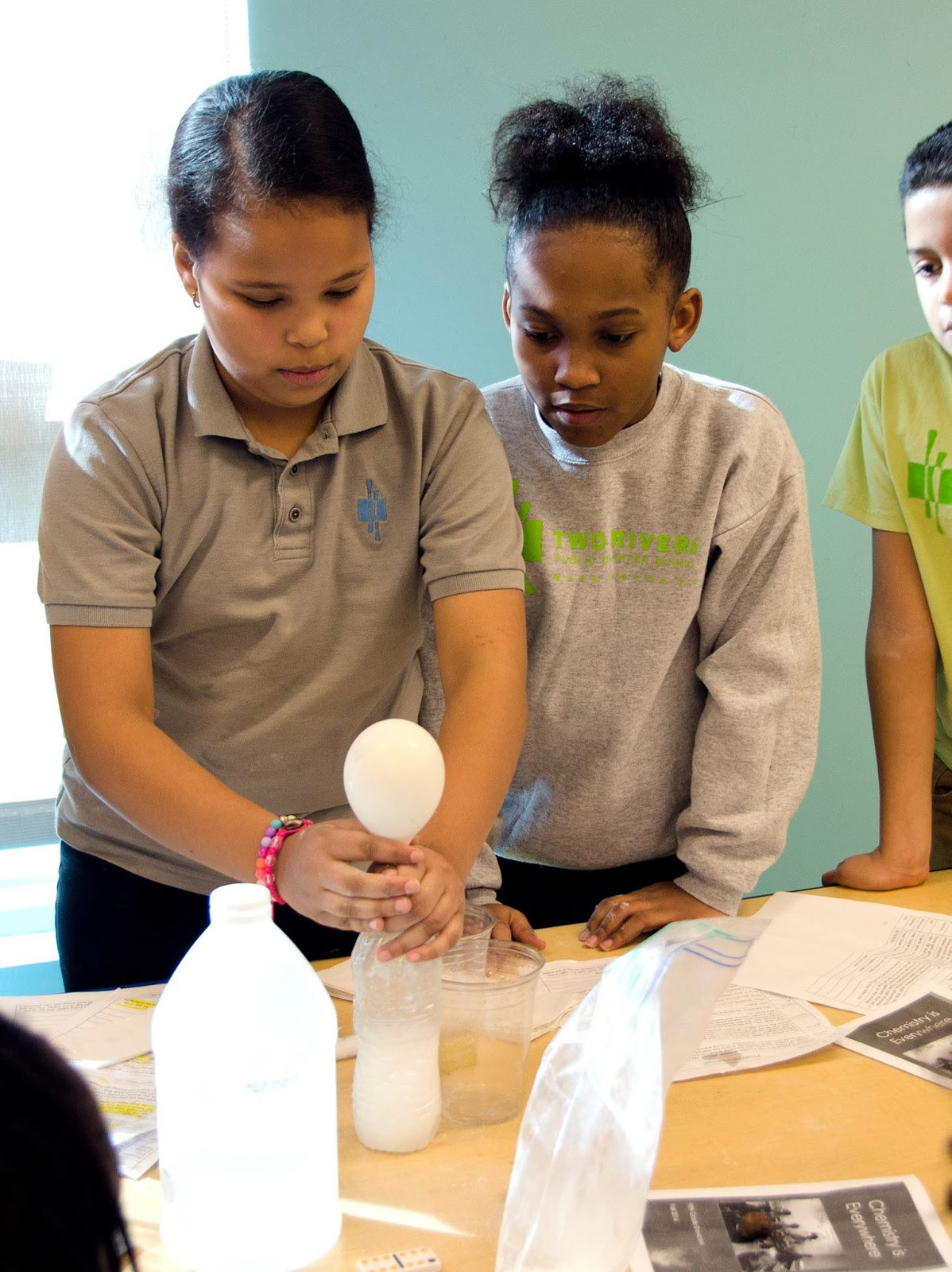

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

Community engagement means listening deeply, learning, and responding. What happens when students, families, or staff question practices central to your learning design?

As one of the founders and instructional leaders of Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., I have recently been grappling with some questions around our values. Specifically, how do we respond when our aspirations for community engagement challenge our practices that are aimed at providing student agency?

On the one hand as a parent-founded school and as an aspiring anti-racist organization we are committed to community engagement. We want to empower the voices of all of our community members, but particularly those members of our community who have traditionally been marginalized whether because of race, economic status, gender, educational attainment, or any other identity.

On the other hand, we want to provide our students agency so that they can be leaders of their own learning. With that in mind, we are committed to challenging the traditional paradigm around grading in schools. Traditionally grades have been designed primarily as a sorting mechanism and are predicated on accurate completion of assignments which may or may not have any relationship to actual student learning. Consequently, we have sought to design a system of grading that empowers students, families, and teachers by aligning grades to standards. Our standards-based grading system assigns grades based on how well students have demonstrated mastery of the skills, knowledge, and understandings embedded in standards. Thus, these grades give all stakeholders a deeper understanding of both what we are aiming toward in students’ learning and where each student is in relation to those targets.

On the surface, both of these aims, community engagement and standards-based grades, don't seem to be in conflict. In fact, both are designed explicitly to provide greater agency to students and families. However, in practice, community engagement means listening deeply and learning from our community. What happens when members of our community question our grading practices?

As I reflect on this question, I am struck by teasing apart the difference between intent and impact. We may intend for our standards-based grading system to provide greater agency to students. But if families, students, and staff members are more confused by the system, then the impact is doing more harm than good. This is not to suggest that we should return to a system of traditional grades that we clearly have seen not working. Instead it challenges us to make our grading system better.

I believe that engaging our community around how to make our standards-based grading system stronger is an integral part of our community engagement. Listening deeply to the concerns of our families, staff, and students and talking through our commitments to the practice are part of how we need to engage.

Our Case for Standards-Based Grading

Since we opened in 2004, Two Rivers Public Charter School has been committed to using a form of standards-based grades. Over the years, some of the technical elements of how we generate standards-based grades have shifted, a result of deepening understanding of the context in which our students are learning and the adoption of the Common Core State Standards. However, our commitment has remained steady.

We believe that the traditional system of grading is broken for several reasons, including:

- Traditional grading systems assign grades by assignment, and don’t tell students much about what they are learning or give any nuance to how they might improve on what they are learning.

- Traditional grades also roll all of that learning into a single letter or number to suggest where a student is in terms of a broad subject area. However, they don’t separate out knowledge, skills, understanding, and effort.

- Traditional grades compartmentalize learning into specific grade bands and thus imply that learning is limited or bounded when a student cannot surpass an A or a 4.0.

The standards-based grading system at Two Rivers is specifically designed to mitigate against these flaws of traditional grading.

- Students are assigned grades based on a standard and thus a given assignment could have one or more grades assigned to it depending on how many standards are associated with the assignment.

- In a given subject area students are given multiple grades across several standards thus giving them a much more nuanced picture of their progress.

- We grade on a five-point scale where “3” connotes mastery of the standard. The additional points on the scale allow for students to surpass the grade-level standard and understand that learning continues beyond a given grade level or course.

- We separate effort or scholarly habit grades from academic grades so that a student’s effort is not equated with their level of skill or understanding in a subject area.

Again the intent is to give students, teachers, and families the detailed information they need about how students are doing.

The Source of the Challenges around Our Standards-Based Grades

Two Rivers is a prekindergarten to eighth grade public charter school. When we are challenged around our grading system, it rarely, if ever, comes from parents or staff members in our early childhood or elementary programs. Our grading system is typically challenged when students reach middle school and grades begin to translate into a transcript for high school admissions and high school credits.

The concerns of staff, students, and families in middle school around our grading are very real because the stakes are very real. If students aren’t able to translate their grades into something that others understand they may not be admitted into an application-only D.C. public high school or a private school. The truth of the matter is that the vast majority of public and private high schools around us use traditional grading systems and have little understanding of standards-based grades.

The concerns of staff, students, and families in middle school around our grading are very real because the stakes are very real.

Community Engagement

Which brings me to community engagement. The Great Schools Partnership defines equitable community engagement as an ongoing, two-way process of building relationships, working collaboratively to support all students, and sharing power.

One of the most common comments that we receive related to our system is that it is confusing. Some students, families, and newer staff members are unsure how students earned the grades that they received. What’s more, when translating these grades into a transcript for high schools, our stakeholders have been unsure how we generate those scores. If our grading system is confusing, we haven’t done our job. If our intent for grades is to provide agency to students, then grades should be clear and easily understood by all members of our community.

To help stakeholders better understand student grades, we do need to do a better job of relating the what, why, and how of our grading system. That communication needs to happen on a regular basis in both formal and informal ways. Regular formal presentations, student-led conferences, newsletters, and progress reports—these are all opportunities to share information about our grading system and how it empowers students in knowing what they are learning. In addition, we should regularly be asking for feedback: Do you understand these grades? Why do you think standards-based grading is used at Two Rivers? How clear are our formal systems of communication? What do we need to do better?

In addition to these formal avenues, we also need to continue to cultivate informal systems of communication like when teachers talk with students about their grades in class, talk with colleagues at the coffee maker about grades, and talk with parents between conference times about student progress. Empowering teachers to have these conversations is part of the community engagement around this system.

In addition, we need to continue to engage with the high schools into which our students matriculate. Just like families, students, and staff at Two Rivers, our colleagues at area secondary schools need to understand how our students have performed in the past and whether or not they should receive high school credit for particular classes. To aid in this process, we have developed a system that translates our standards-based grades into a traditional 4.0 scale. The sole purpose of this translation is to make our students’ performance in individual classes comparable to peers at other middle schools that use more traditional systems of grading. In addition, we maintain connections with the admissions offices at high schools to better understand what they are looking for in student admissions, and also ensure our students aren’t disadvantaged because of our grading system.

Ultimately, the goals of communication with students, families, staff, and area high schools should not be just to prop up a system that isn’t actually serving our students well. Instead the goals should be what Great Schools Partnership describes so clearly: ongoing, two-way relationship building, working collaboratively to support all students, and sharing power. This requires that we better understand parent and staff concerns about a non-traditional grading system. Ultimately, it means considering how our grades do and don’t provide students with agency. Through parent and student feedback, we need to get better at understanding what they need and how we can provide it, not how to best defend our specific system of grading.

Working with Students and Families to Improve Standards-Based Grading

It would be easy to assume that because there is pressure to change our grading system, we should pivot back to a traditional system of grading in our middle school. However, listening to our community and the voices of those who don’t fully understand or agree with our system does not mean abandoning a practice that is designed to empower students and families. Because traditional grading systems are embedded in the culture of schools and schooling in the United States, there will inevitably be challenges to a structure that bucks those traditions. In addition, because we are steeped in the cultures of traditional schools and power structures, the new system that we design can be just as alienating.

Ultimately we need to keep focused on providing agency to students and families as our North Star—through authentic community engagement that will improve our standards-based grading system. We need to work together. If we are able to design a system that students and families can utilize effectively to make informed decisions about their educational choices, our grading system is working. If students are better able to advocate for themselves around their learning, our grading system is working. If students see that our grading system doesn’t hinder their acceptance to highly competitive high schools, our grading system is working. In as much as these goals aren’t being met, understanding the concerns of our students, our families, and our staff is the only way that we can make the system better.

Photos courtesy of Two Rivers Public Charter School.