Designing for Equity

Who Gets to Be an Inventor? Using a Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Approach to Help All Students See Themselves as Inventors

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

All students deserve to see themselves as inventors. Project Invent updated its curriculum and programming to be culturally responsive, sustaining, and equitable in order to make that possible.

All Students Deserve to See Themselves as Inventors

At Project Invent, one thing we like to say is, “We live in a world where everything is designed. Therefore, you can play a role in designing it.” From products and technology, to laws, our cities, our treatment of different genders, and more—many things we see around us are made by design, and this insight helps students imagine how they can play a role in designing a better world.

Project Invent Curriculum Slides: 1) We live in a world where everything is designed. 2-3) But not all designs are good. 3) How can we design a better world?

However, students are not equally empowered to see themselves as inventors. They may learn how to invent and develop 21st-century skills, but may still feel that invention (and STEM in general, for that matter) is not “for them.” As a group of inventors and designers ourselves, the Project Invent staff knows that anybody from any background can be an inventor. To that end, we’ve intentionally reflected on all aspects of our programming, looking at how it can facilitate learning experiences that empower all students to feel confident in embodying the identity of an inventor.

Project Invent’s Approach to Program Evaluation

Our team evaluated our entire program—educator trainings, events, educator and student support systems, and curriculum. We currently conduct this process annually at each team retreat to ensure our programming aligns with our theory of change.

Snapshot of a mapping exercise from a Project Invent staff retreat. We consider how each offering supports Project Invent’s theory of change, and how it supports students in developing key mindsets in particular.

The program evaluation process has helped us continually iterate on our program to ensure we’re best serving our educators and students. In the past couple years, we focused on student events, introducing new offerings like the Student Kick-Off and Pitch Coaching. Our Student Kick-Off event emerged after we learned that students needed more support in building empathy. The event was then designed to focus primarily on supporting students in building empathetic, empowering, and mutually beneficial relationships with their Community Partner (our version of a “user” in the traditional design process). Our Pitch Coaching events, which give students the opportunity to practice a product pitch in preparation for Demo Day, emerged when we noticed that some teams felt more confident than others in preparing and improving upon their pitches. We believed that some of this might be due to inequitable supports across teams, particularly when comparing teams at more resourced versus less resourced schools. Pitch Coaching was implemented to help put all teams on equal footing, supporting both the Ambition and Agency student mindsets in our theory of change.

Evaluating the Project Invent Curriculum

After iterating on our student events, we knew it was time to focus on our curriculum. The Project Invent curriculum, which is an open source curriculum available to any educator, is the backbone of the Project Invent experience. While our student events and supports enrich the invention experience, our curriculum serves as the primary tool educators and students employ in their invention journey.

After launching the Project Invent curriculum in 2018, we began collecting feedback from Project Invent Educator Fellows and other educators in our network. In 2022, we conducted a formal feedback process of our curriculum with our inaugural Educator Steering Committee. This diverse group of seven current and former Project Invent Fellows is compensated to provide strategic guidance to Project Invent’s programs and strategic objectives.

In addition to these formal feedback collection processes, we also relied on our own staff’s years of experience facilitating curriculum activities in our annual Summer Institute professional development trainings. Finally, we collected countless anecdotes and student stories that helped us learn where the strongest parts of our curriculum were, and where we had opportunities to further develop.

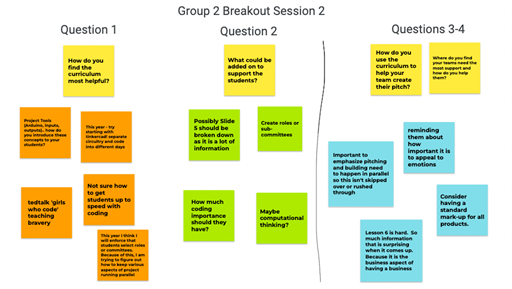

Snapshot of a curriculum feedback session with the Project Invent Educator Committee. The committee evaluated each curriculum module, as well as the curriculum as a whole.

Student Inspirations

Emma Hernandez from TEDxKids@ElCajon 2023

In her recent TEDx talk, Emma Hernandez shared that the world needs to be more inclusive for people with disabilities and shared an adaptive toothbrush prototype that she helped to create. Emma, like so many Project Invent students, sees the invention process not just as a classroom project but as a way to create change in the world around her.

- Lesson 1: We learned that our curriculum and our program meaningfully empower students to invent for community impact. This doesn’t only extend to a single project. Rather, they become inventors, recognizing that they have the agency to create change in any aspect of their communities.

- Lesson 2: Emma and many other students tend to see our program as one that helped them invent specifically for people with disabilities. We learned that we needed to diversify the examples students see in our curriculum beyond inventions for people with disabilities so that they understand that they can invent for any issue they care about.

Emma Hernandez speaking at TEDxKids@ElCajon 2023. Source: Screenshot from TEDxTalks YouTube video.

Angel Fernando Avila Ponce, Project Invent student from Denver, Colorado

Angel Fernando Avila Ponce created an invention in Project Invent as a high school junior. She is now a senior who decided to attend the University of Denver next year to major in mechanical engineering.

- Lesson 1: We learned that students’ life trajectories change because of their Project Invent experience. New pathways open up that they weren’t aware of before, or new specialty areas are discovered that they previously had never imagined.

- Lesson 2: We also learned that not all students feel empowered to see themselves as inventors. It’s essential that all students see invention pathways available for them, and we realized that the examples presented in our curriculum and programming have a direct impact. We knew there were opportunities to make our curriculum more culturally responsive to the diverse students participating in our programming.

Team Squggle: A Project Invent team from White Salmon, Washington

The students in Team Squggle have clearly developed a trusting, empowering, and mutually-beneficial relationship with Angela, their Community Partner. This relationship helped them build a toy that uniquely responds to Angela’s desires, and shows how invention can help others feel seen, heard, respected, and empowered.

- Lesson 1: The words students use to talk about our Community Partners matter, but we learned that not all students are empowered with the language that makes their Community Partner feel seen, heard, and respected. We knew that we wanted every Community Partner relationship to be like Team Squggle’s.

- Lesson 2: It’s crucial that students develop empathetic, meaningful, and powerful relationships with the Community Partners. They must recognize that their Community Partner is a member of their team, not someone they are “saving” or “rescuing.” We learned that this lesson could be more evident in our curriculum, and we wanted to include more supports to help teams build strong relationships with their Community Partners.

The members of Team Squggle sharing pivots, realizations, and Community Partner quotes in their Idea Review pitch.

Defining Our Areas of Focus for Curriculum Development

The feedback and stories we collected helped us identify key areas of focus for curriculum development:

- Cultural responsiveness to students of underrepresented backgrounds (in particular BIPOC youth) and diverse representation of Community Partner issue-areas (disability & non-disability examples, individual & societal issues)

- Guidance on building mutually beneficial & empowering relationships with Community Partners

- Stronger onramps to learning technology to improve accessibility, particularly with students less confident using technology

1. The Culturally Responsive-Sustaining STEAM Curriculum Scorecard

Although our team was very familiar with Marian Wright Edelman’s idea, “You can’t be what you can’t see,” and the importance of representation within our materials, we felt that we were in need of a more robust framework by which to evaluate our curriculum. After increasing diverse representation in our curriculum, what could we do next? How could we strive for improvement and development over time, knowing that this work is never done?

We took some time to research methodologies for creating a culturally responsive curriculum and eventually landed on a tool we liked: The Culturally Responsive and Sustaining STEAM Curricula Scorecard (CRE STEAM Scorecard). Developed by NYU’s Metro Center and released in 2021, the CRE STEAM Scorecard was designed with a belief that “students deserve to learn about STEAM subjects in ways that reflect themselves and their communities; are critical of power, identity, problems and solutions; and present a vision of STEAM that includes people of color, women, LGTBTQ people, immigrants, people with disabilities and more.” Taking this scorecard as inspiration, we got to work.

First, we reviewed all thirty statements scored by the CRE STEAM Scorecard. The statements fall into the following categories: Representation, Social Justice, Teachers’ Materials, and Materials & Resources.

Next, we focused on our timeline. We knew we wanted to relaunch our curriculum before the upcoming program year; we felt we couldn’t wait. Thus, we made the difficult decision to choose just a few statements from the CRE STEAM Scorecard that we believed could help us make the most meaningful improvement in our curriculum. We decided to “grade” our curriculum on the following statements:

Representation

- The curriculum elevates mathematicians, artists, and/or scientists with historically marginalized identities (i.e. non-binary or trans people, women, people of color, people with disabilities, working class people, multilingual people) and their discoveries.

- The curriculum has photos/pictures, names, scenarios, and text that reflect the experiences and interests of students of color in your community.

Social Justice

- The curriculum provides avenues for students to see STEAM as a way to understand and improve their world, take actions that combat inequity or promote equity, and connect learning to social, political, and/or environmental concerns.

- The curriculum presents social situations and problems not as individual problems but as embedded within a societal and/or systemic context.

Materials & Resources

- Curriculum rigor is not dependent on access to resources, materials and technology that students and schools may not have. In other words, the curriculum materials are fully accessible; all resources, materials and technology options are rigorous and interesting. (Ex. If students can engage curriculum materials with a computer or paper, the paper materials should be just as rigorous, interesting, and engaging as using the computer).

We decided to consider the fourth “Teachers’ Materials” category separately; as we were developing a new Educator’s Curriculum Handbook to be released in Summer 2023.

Finally, we worked as a team to evaluate each module of our curriculum using the statements we selected. This framework was a tremendous help for our team. It helped us identify areas of our curriculum where we’ve attempted to address each statement, consider whether or not each attempt was problematic, create a “score” for each module, set goals for our “desired” score, and then review our curriculum closely through the lens of each of our selected statements.

Some improvements you’ll notice in our curriculum because of this work:

- New “Behind the Design” profiles that feature inventors who are diverse in age, race/ethnicity, language, professional background, and invention area. Each profile features unknown histories of inventors, stories, quotes, and photos.

- A broader representation of invention areas. We added areas like music, cooking, and sports to “traditional” areas of focus like tech gadgets and healthcare. For example, in addition to learning about innovation of MRI machines in healthcare, students also watch a video about football player and inventor, Shawn Springs, and his invention to prevent concussions on the football field.

- New vocabulary slides for English Language Learners.

- Diversified types of inventions represented in our curriculum to better reflect the diverse interests of students and communities. In addition to seeing inventions related to supporting individuals with physical disabilities, we also highlight topics including mental health, environmental sustainability, and animal welfare.

“Behind the Design” example about inventor and entrepreneur, Sunita Mohanty

New video vignettes about diverse inventors, including football player and entrepreneur, Shawn Springs

Showcasing diverse invention areas. In this case, we show examples of physical disability, environmental sustainability, access to quality food, and mobility.

2. Combating Ableism in Student/Community Partner Relationships

After reviewing our curriculum with the CRE STEAM Scorecard, we focused on how we could best educate about ableism and facilitate empowering, meaningful, and mutually-beneficial relationships between students and their Community Partners. Within the invention process, ableism can look like the following:

- Disempowering Language: Often unintentional, students may use disempowering language, such as being a “victim” of one’s disability or referring to individuals experiencing poverty as people who “have nothing.”

- Objectification: On the flip side, Community Partners can be objectified for inspiration. For example, a student might refer to their Community Partner as “so brave” or “inspiring” for dealing with a challenge that the Community Partner may not see in a similar light.

- Using Unpreferred Language: Many students are unfamiliar with Person-First Language vs. Disability-First Language (ex. person who is blind vs. blind person). When working with Community Partners, it’s important to ask how someone prefers to identify. This often leads to…

- Treating Groups of People as a Monolith: Students can sometimes fall into the trap of believing their Community Partner is representative of a particular group. For example, a team working with a person experiencing homelessness might believe that person’s opinions are representative of all people experiencing homelessness.

At Project Invent, every invention team works with a Community Partner. Further, the success of their experience in the program rests on this crucial relationship between the team and their Community Partner. Teams that build strong, trusting, and mutually-beneficial relationships with their Community Partner begin to see them as part of the team. When students run into challenges, they persist because they know their invention can make a real impact for a real person. When they run into a roadblock, they ask their Community Partner for feedback and support. We’ve noticed that teams with the strongest relationships have the strongest outcomes for both the students and the Community Partner.

At Project Invent, we believe that the entire invention process is deeply enriched by this important relationship with a Community Partner. Thus, we wanted to explore opportunities to help students develop deeper empathy, listen more closely and actively, and learn how to use empowering language. While our teams work with a wide variety of Community Partners across a wide range of focus areas (ex. environment, animal welfare, etc.), a large number of our teams work with Community Partners with visible and invisible disabilities. To this end, we knew our curriculum should help students both learn about and combat ableism.

With the above intentions in mind, we set out to introduce deeper supports for building strong, empowering relationships with Community Partners, including these changes:

- New reflection activities that help students dive deeper into design in the world around them and unpack meaning using a technique called Visual Thinking Strategy. These reflection activities help students connect the designs to larger social systems of inequity, and help students learn about human-centered design and inclusive design principles.

- Increased emphasis of Community Partners as part of the invention team: Students are encouraged to continually pause in their design process to collaborate with and seek feedback from their Community Partner in order to inform future iterations of product design.

- Shifting language from finding “problems” to “areas of focus.” Increasingly, Community Partners don’t see what students are inventing for as “problems” to be “solved.” Furthermore, we knew it was important for students to view Community Partners as experts of their own experience first, and explore how their Community Partners prefer to describe their experiences. Thus, we renamed the “Need Finding” curriculum module to be titled, “Empathize + Define,” and shifted language throughout the curriculum as well.

- Additional research activities to help students come into their Community Partner interview more informed, while also leaving room with their Community Partner to “fill in the blanks” with their own experiences.

A curriculum activity that explores a redesign of the modern pill bottle, with reflection questions to help students consider how ableism impacts aspects of the world around them. Students learn about inclusive design and how designers work with clients to create a better world for all people.

To help students view their Community Partner as an essential member of their team, the curriculum pauses them throughout the design process to consult their Community Partner. We also encourage students to consult other users with an understanding that their Community Partner is not representative of all potential users of their product.

In this research activity, students begin researching potential areas of focus to build their invention around. Students engage in several research activities throughout the invention process, which supplements the collaboration they do with their Community Partner.

3. Building Onramps to Technology

Finally, we improved accessibility to technology with our curriculum relaunch. In the previous version of our curriculum, we asked all students to use Arduino as the microcontroller that would control the physical technology of their invention. As inventors and engineers, Project Invent staff members love Arduino because it is not only used in classrooms but also by professional makers and inventors. Using Arduino provides students with skills that they can easily translate into their postsecondary education or careers. While not always the most accessible, we wanted to push students to be ambitious in learning new tech skills, and we knew that learning Arduino would help students develop resilience and ambition through the process of productive struggle.

However, in the past few years, we have continued to receive feedback that learning Arduino is particularly challenging for students with limited exposure to coding and electronics. While all students are capable of learning Arduino, we began to realize that for some, learning Arduino would not be a path to developing resilience if it only resulted in frustration. Further, students were already demonstrating significant ambition by just working through the beginning stages of learning coding and electronics before even touching an Arduino.

To develop resources that were accessible to all students, we started with building stronger onramps to technology and developing scaffolds and supports to help students learn the basics of programming and electronics before jumping to more challenging platforms. Specifically, we decided to integrate instruction in Micro:bit in addition to Arduino. Micro:bit is an open source hardware that was created specifically for use in the classroom. With its user-friendly platform, block coding functionality, and accessible learning tools, we knew it was a perfect fit for providing onramps to learning that would better serve the diverse students working through our curriculum.

We also enhanced scaffolds for students to learn concepts such as developing pseudocode, identifying the inputs and outputs of an invention, planning out how to approach the coding process for an invention, and debugging written code.

During the building phase of invention, students deepen their knowledge about inclusive design, write pseudocode for their inventions, and plan their approach to building their invention. The “Eggs-Iting” example shows how students can convert an idea into a series of actionable steps during a product build.

Responding to User Feedback: Always in Beta

We have learned so much through the process of revising our curriculum. From listening deeply to feedback, to learning new frameworks for approaching curriculum design that allows all students to see themselves as part of the invention process, we have taken new tools not only into this project, but into all future processes of revising our curriculum. However, if I had to define one key lesson learned, it’s that we are “always in beta.” Our work of remaining culturally responsive is never done. Our work in encouraging allyship and mutually-beneficial community partnership is never done. Our work in continually listening to our users—our educators and students—is never done. In the spirit of invention, we will keep on responding to feedback and iterating.

In light of this, we invite you to download the curriculum, look through it, and share any feedback that you have. We already know that we’d love to find more stories of diverse student inventors to include in our curriculum, and invite you to share stories with us if you have them. Finally, if you’d like to join us in this journey or engage in a community of practice around invention education, we invite you to join our Educator Fellowship, where we support educators with year-round professional development to implement our curriculum into their unique classroom settings.

Image at top: Screenshot of Emma Hernandez presenting at TEDxKids@ElCajon, taken from TEDx Talks video.