Designing for Equity

Designing for Race Equity: Now Is the Time

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

School teams eager to make an equity-centered response to the impacts of the pandemic can use the five principles of the equityXdesign framework; examples and stories from schools offer inspiration and a place to start.

Racism and inequity are products of design. They can be redesigned.

—Caroline Hill of 228 Accelerator, Michelle Molitor of The Equity Lab, and Christine Ortiz of Equity Meets Design

According to Andrew Plemmons Pratt, director of school launch and incubation at CityBridge Education in Washington, D.C., the COVID-19 pandemic is forcing us all to reconsider many elements of public education. We can see now with raw and tragic clarity the savage inequities of our education systems. Our opportunity then, he argues, is to solve for those and prepare for the ongoing shocks that will follow.

The equityXdesign framework has been a guiding light at CityBridge Education, from their Breakthrough Design Fellowship in 2017-18 to their current School Design Fellowship. However, the principles and methods can also help educators craft responses to the “new normal” of closed schools and interrupted learning.

In this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, Andrew explains the equityXdesign framework and shares examples and stories from schools with whom CityBridge has worked. In this way, he hopes to provide a useful starting point for teams eager to take an equity-centered approach as they respond to the immediate, mid-range, and long-term impacts of the pandemic. The five principles that comprise the equityXdesign framework are:

- Design at the margins

- Start with yourself

- Cede power

- Make the invisible visible

- Speak the future, design the future

Design at the Margins

“Design at the margins,” the first principle, pushes educators to design with the students at the edges of a community in mind. In many schools, those at the margins are often disempowered based on their identity or poverty. Given the long history of racism in schools, CityBridge centers race in our work. The foundational belief behind this principle is that what works for those at the margins will be good for all learners.

One school that took this principle to heart is Yu Ying Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., a Chinese immersion elementary school and member of our School Design Fellowship. Although they are among the most racially diverse schools in the country, they had nagging achievement gaps between Black and Latinx learners and students who were Asian or white, starting as early as first grade for math and kindergarten for ELA.

To address these gaps and to build a more inclusive school culture, an eight-person team began a design project in 2019 to focus their attention on the most marginalized within the school. They identified students of color across four grade levels, including those who were receiving interventions already, who had experienced a family trauma, whose parents were divorced, who lived in neighborhoods far from the school, or who were English Language Learners.

The two primary methods used in their project were empathy interviews with learners and student shadowing, which involves following learners through their school day (or a portion of it) in order to understand as well as possible what their experience looks and feels like.

At Yu Ying, Executive Director Maquita Alexander set aside several hours of one day to shadow a student who was struggling but not yet failing academically and who seemed disconnected from teachers and other students. Maquita’s quiet observations confirmed that the student was neither disruptive nor engaged. Instead, the student was invisible. Her team combined these observations with findings from empathy interviews and additional faculty data, revealing that teachers knew students academically but did not “see” them outside of their school work.

Because the Yu Ying team had focused on students at the margins, they were able to articulate the challenge they wanted to tackle in their design work: “Staff need ways to offer opportunities for academically struggling students to express who they are in order to be seen for their whole selves within the school context.” The route to defining the problem was deliberate, and the path to testing and refining solutions has also been long—but that is an important facet of an equity-centered design: it favors process over urgency.

Start with Yourself

The equityXdesign principle “start with yourself” reminds us that our intersectional identities can give us superpowers as well as crippling blinders. We have to design with an awareness of how our race, gender, income, citizenship status, and other characteristics shape how we see the world.

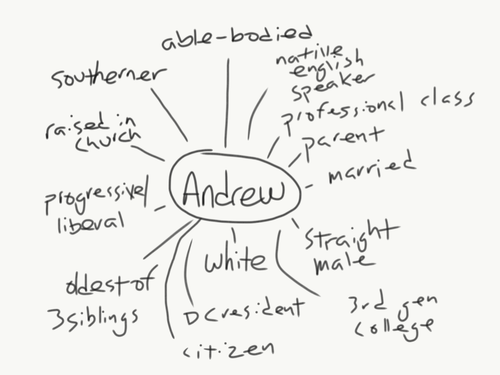

During the 2017-18 school year, we began our work with each educator cohort in the Breakthrough Design Fellowship with an identity mapping exercise, modeled on a National School Reform Faculty protocol called “The Paseo.”

A concept map created by Andrew depicting key identifiers of his identity

Each participant worked independently to map key identifiers of their identity around their name. Then they partnered up in “constructivist listening dyads.” In constructivist listening, each partner gives full attention while the other processes their ideas aloud. The point is not to generate conversation, or to offer advice or analysis, but for each person to have equal time to share openly and honestly.

Prompts begin with identity exploration, like, “With which descriptors do you most strongly identify? Why?” or “With which descriptors do others identify you most strongly? How do you feel about that?”

Then the prompts bend toward how we, as adults, have been shaped by these identity markers in our work as educators, such as, “Talk about a time when your perceptions of a person’s identity caused you to do something that held them back,” or “Talk about a time when your perceptions of a person’s identity caused you to do something that moved them forward.”

This sort of reflection on who you are and how the “skin you're in” shapes your relationships with others is particularly important for the empathy work described above. Otherwise, your biases may lead you to lower your expectations of the students or families you’re talking to. Some aspects of your identity may also prevent others from trusting you.

Cede Power

The “cede power” design principle urges educators, who usually hold the power, to share it with students and families as they design learning.

One way CityBridge has done this is with a “spectrum activity,” in which students, from elementary grades through high school, vote with their feet when describing their experience of school. Responding to prompts like, “In my school, my voice matters,” and “What I am learning in school matters,” students move from one part of the room where a sign reads “Agree” to the other side of the room where a sign reads “Disagree.” Learners are empowered to move to a place on the spectrum that expresses their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement. In this way, the activity is intended to break precedent: instead of giving students little voice in the design of their learning experience, we center them as co-designers.

Another activity that addresses ceding power is a fishbowl experience. During the Breakthrough Design Fellowship, we designed and facilitated a fishbowl conversation for a group of older students who attended “opportunity schools” (also known as alternative schools). The learners sat in a circle and responded to a series of prompts that enabled them to talk candidly with one another about their experience in school while teachers and school leaders sat on the outside of the circle. Students became the center of focus, while the adults who teach them had to just listen.

Afterwards, teachers and other adults responded to their own reflection prompts around assumptions they’ve made about their students, the problems they face, and the sources of their challenges. Participants were also invited to share ways their mindsets had changed as a result of the fishbowl activity.

One teacher reflected: “I used to think students wanted space to talk with each other. Now I think that students want space to talk to teachers, too.” Another teacher said: “I used to think students didn’t give much thought to how a school functions, but now I think they may care more than the adults.”

One of the students wrote: “I used to think that my voice didn’t matter, but now I think that my opinions are heard.”

Maquita and her team at Yu Ying have grounded their work in the idea that student voices matter as well. “If the answer comes from them,” she says, “that’s success” in the design process.

Make the Invisible Visible

“Make the invisible visible” means bringing power dynamics, such as who has decision-making authority, to the table and naming the dynamics instead of pretending those hidden rules are not there.

In the most traditional formulation of design thinking, designers are the ones with the power. In an education context, the designers (educators) ask users (students) about their experience. Then the designers disappear with that information, build a solution, and return to give that solution to the users. This approach, where designers consult with stakeholders, is “user-centered design,” as depicted in the diagram below.

Spectrum of design power dynamics, from the equityXdesign Collaborative

Just naming that relationship begins to make power dynamics visible. Some circumstances may call for a process where educators do little more than consult students. But in other situations, the more deliberate and equitable pathway is to move along the spectrum to “co-design,” where stakeholders become part of the design team. Turning the dial all the way to “user-created design” means handing the design tools over to students and entrusting them with power usually reserved for adults. There is also an obvious point of overlap between principles: making invisible lines of power visible can lead logically to a ceding of that power.

In CityBridge’s School Design Fellowship program, we also use a set of observation tools focused on student identity development and affirmation. These tools, informed by research from the science of learning and development, can help make visible the ways that schools either affirm and support students in their personal identities or alienate and minimize who they are in the world.

In particular, we draw upon Transcend’s comprehensive “Designing for Learning Primer” on learning science and a simple set of cards that summarize research findings from psychology and cognitive science, with insights about how identity intersects with learning. We’ve found that schools that honor this research help students develop self-understanding, build a sense of belonging, and navigate identity and stereotype threats.

For example, when we took Design Fellows to visit schools in Chicago in October 2019, school leaders reflected on these connections between identity and learning before stepping off the bus and into the schools. They selected identity-connected principles to guide their observations in hallways and classrooms, such as: “What about the school culture and environment helped or hindered students in building a sense of belonging?” and “How did adults support students in navigating threats to their identity?”

After visiting Barbara A. Sizemore Academy, an African-centric charter school in the Englewood neighborhood of Chicago, one Fellow wrote: “This was one of the most inspiring school visits I have ever been on. Most inspiring was the students’ ability to describe how the culture of the school has transformed their personal identities and lives.”

Reflecting on mindset shifts over the course of the visits, another Fellow shared: “I used to think that a strong SEL (social emotional learning) model only needed to address emotions and behavior. Now I think a strong SEL model must include some basic work around identity.” The identity insights served as a magnifying glass for elements that fostered inclusion and exclusion.

To be clear, these are two very different ways of thinking about “making the invisible visible.” Bringing students into the design process requires very different moves from doing school observations that focus on identity development and affirmation. But each method supports equitable design by pushing educators to shift their perspectives and examine assumptions about power and belonging that might otherwise go unquestioned.

Speak the Future, Design the Future

Finally, the “speak the future, design the future” principle acknowledges that the language we use to talk about education sets the limits of our imagination, so more equitable schools require critiquing and changing the way we talk and write about learning.

In their 1997 book chapter, “Changing the Discourse in Schools,” Eugene Eubanks, Ralph Parish, and Dianne Smith open their argument with a definition of “hegemonic discourse,” the way that white reformers with power over schools talk and write:

[T]he current dominant discourse in schools (how people talk about, think about, and plan the work of schools and the questions that get asked regarding reform or change) is a hegemonic cultural discourse. The consequence of this discourse is to maintain existing schooling practices and results. We call this hegemonic discourse, Discourse I.

They contend that Discourse I (DI) maintains things as they are in schools. In contrast stands Discourse II (DII), which is about liberation and transformation. For example, consider the difference between “dropout,” which falls under DI, and “pushout,” which is DII. The term “dropout” blames students for failing at school and leaving. “Pushout,” however, shifts the problem to adults and the school structures that alienate students, make it difficult for them to succeed, and ultimately drive them away from a school system that was never designed for them. Whereas the DI term makes power invisible, the DII term unmasks that power and forces us to question a system that oppresses students.

This table, from the Bay Area Coalition for Equitable Schools, illustrates examples of Discourse I and Discourse II. It is based on "Changing the Discourse in Schools" by Eugene Eubanks, Ralph Parish, and Dianne Smith in Race, Ethnicity, and Multiculturalism: Policy and Practice.

When CityBridge School Design Fellows visit schools, we use this discourse framework to talk about what we see and what sort of language we hear from school leaders. We also use it to check the language and ideas that educators generate during the design process.

For example, at a gathering of Fellows in January 2020, I used the lens of DI and DII to facilitate an “equity pause” during a brainstorming session. Equipped with Sharpies and sticky notes, on their feet to keep energy up, and with a time limit to add urgency, teams first generated as many ideas as they could for testable solutions to challenges facing their schools.

The Yu Ying team, for instance, brainstormed how their school might offer opportunities to academically struggling students to express themselves outside of academics in order to be fully seen and valued. They captured lots of ideas on Post-Its, from art contests to new clubs to classroom jobs.

The equity pause then challenged teams to sort the whirlwind of sticky-note ideas along a spectrum of DI to DII. This was an opportunity to organize and filter their thinking for a more transformational approach. For the Yu Ying team, the ideas at the end of the spectrum labeled “Discourse II” included having students design assemblies and workshop opportunities and documenting student work with student photographers. This group of ideas focused on shifting power and point of view to the Yu Ying students, and the team’s resulting prototype encompassed a student-designed, written, produced, and documented play focused on elements of social-emotional learning. Pausing to check the language we use to describe new ideas helped them shape a vision of what could be different for those students at the margin.

Bringing It All Together

The equityXdesign framework is not a checklist but instead helps educators to show up in the design process in a way that centers equity questions—and still harnesses the creative power of design thinking.

As you embark on your own school design projects, I hope that some of these methods can serve as inspiration and practical guidance for how to go about doing equitable school innovation. Please let us know how they work for you.

Resources

- This Shadow a Student workbook from shadowastudent.org and an adapted version from Transcend provide tools and instructions for shadowing learners.

- Transcend has created a planning and facilitation tool for empathy interviews with learners and other stakeholders. Empathy Techniques for Educational Equity, from David Clifford and the Stanford d.school, focuses more specifically on interviews with an equity lens. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Panorama Education now offers free access to the questions from their Student Well-Being and Distance Learning surveys to help educators understand how students and their families are experiencing the current moment.

- To support you to facilitate your own activities and conversations with learners as co-designers, CityBridge shares the slides and prompts they used with the School Design Fellowship for the high school fishbowl and the student spectrum protocol and elementary/middle school fishbowl conversations.

- Caroline Hill, founder of 228 Accelerator, delivered this keynote address at the 2017 iNACOL Symposium about how her intersectional identity has shaped her as an equity designer. In this interview with the Aspen Institute, she describes her work with students, policymakers, and law enforcement to tackle truancy in Washington, D.C., schools.

- The Paseo or Circles of Identity protocol from the National School Reform Faculty, describes one way to facilitate an identity-mapping activity.

- The Harvard Project Implicit tests (IAT), a series of brief online assessments, aims at surfacing unconscious ideas we can all carry that might give us preferences, such as for lighter or darker skin, for men or women, or for disabled or able-bodied people.

- This tool from CityBridge’s School Design Fellowship School Visit Workbook was designed to support school visits for Washington, D.C., school leaders to Chicago in October 2019.

- Transcend’s Designing for Learning Primer, along with the set of cards and other tools, can be accessed for free (with sign-up).

- In “Changing the Discourse in Schools” by Eugene Eubanks, Ralph Parish, Dianne Smith, in Race, ethnicity & multiculturalism: Policy & practice, the authors address Discourse I and Discourse II, asserting that the most serious question facing substantive school reform is how to create Discourse II in school cultures.

Acknowledgements: Many of these methods were created by our former colleague at CityBridge, Caroline Hill, who is the founder of 228 Accelerator. The equityXdesign framework is the brainchild of Caroline Hill, Michelle Molitor from The Equity Lab, and Christine Ortiz from Equity Meets Design. Our partnership with School Retool helped us to learn many great design tools. Finally, Transcend Education builds and shares an enormous volume of methods for school R&D.

Photo at top courtesy of CityBridge Education.