Designing for Equity

Diversity, Equity, and Next Gen Learning

Topics

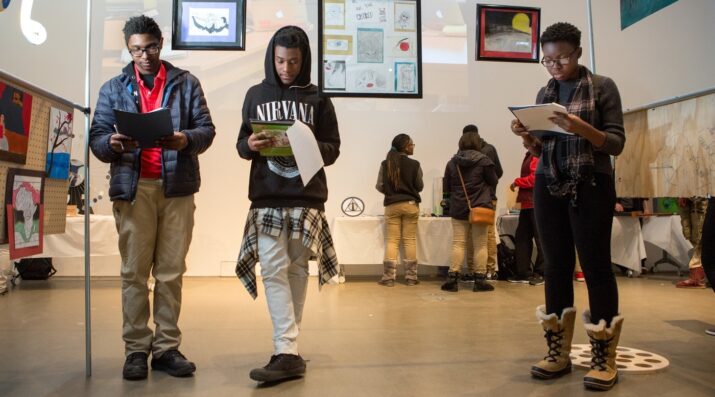

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

To realize its full potential, next gen learning needs to be happening in the places where young people face the greatest barriers to success, and where schools are just as likely to be part of the problem as the solution.

Philadelphia, where our school is located, has the dubious distinction of being on two top 10 lists you don’t want to be on: it is one of the most racially segregated cities in the nation and one of its most economically divided. And it has plenty of company: New York, Detroit, Cleveland and Milwaukee are all on both lists, and Chicago and Boston aren’t far behind. In these cities (and countless others), racially and economically segregated schools and neighborhoods are much closer to the norm than the exception. Whether we call ourselves next gen learning, or deeper learning, or student-centered, or personalized, or John Dewey with a Chromebook, we need to acknowledge this reality: to realize its full potential, next gen learning needs to be happening in the places where young people face the greatest barriers to success, and where schools are just as likely to be part of the problem as the solution.

While places like the High School for Recording Arts, WHEELS, or Youthbuild Philadelphia set a powerful example, in reality the number of ‘progressive’ schools serving highly disadvantaged communities remains vanishingly small. To change this, we need a change in both mindset and systems.

In terms of mindset, we need to let go of the idea that the academic work is the main thing, and everything else merely supports that. This sort of thinking permeates education generally; we think the reason to invest in healthcare or mental health or extracurricular programs is because they will improve grades or test scores, as if that were the only good reason to offer these supports. In next gen world, this manifests in a fixation on project based learning (PBL) or personalization as the real work, with elements like community building in a subordinate role. The problem with this way of thinking is that it relegates critical work to the margins.

At the Workshop School, we’re realizing that what matters most to students’ long-term success (especially disadvantaged students) is just as much about restorative and trauma-informed practice as it is PBL. (The reverse is also true: we have worked with schools that are very strong on youth development principles and practices, but have realized that they are at odds with traditional approaches to teaching and learning.) As educators, we need engage students in authentic learning and help them build the skills that are most needed in college and career. But we also need to be youth workers, focused on seeing students’ strengths, being attuned to the challenges they face in life, and committed to meeting them where they are and supporting them without judging.

Changing our systems needs to happen at two levels. The first involves drawing clear lines between supports at the classroom level (for which teachers are primarily responsible) and those available at the school level. Our school is very much a work in progress on this front. When a student is sent to the office to talk with a counselor or an administrator, the line between support and discipline is often blurry, as are the procedures and conditions under which that student returns to the classroom. One of our goals in the next academic year is to help all staff develop a repertoire of trauma-informed practices in order to effectively engage students who are struggling, and to further clarify and articulate how restorative processes work at the school level.

The most challenging aspect of shifting systems to support next gen learning in high poverty schools is, not surprisingly, lack of resources. Tiered intervention models like Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports (PBIS) or Response to Intervention (RTI) have been around for a long time, and all seek to delineate the links between classroom support and prevention and more intensive levels of intervention. In most under-resourced schools the challenge is that the intensive interventions that are supposed to be in place simply are not. Money is certainly a factor here, but so is the decision to invest heavily in security (metal detectors, police and other security officers) over mental health and other student supports.

The good news is that this work has begun to receive significant attention in recent years. Programs like the Deeper Learning Equity Fellowship have highlighted school and classroom-level projects aimed at improving systems and practices to support our most disadvantaged young people. And here in Philadelphia, the HIVE @Springpoint is bringing together schools and youth development organizations that typically exist in surprisingly different ecosystems to collaborate on expanding and supporting the use of trauma-informed practices.

This work needs to continue. But we also need more opportunities to connect and collaborate nationally. I am constantly on the hunt for new schools to visit, and I’ve been lucky enough to see quite a few. Nearly everywhere I’ve been, these schools have operated in relative isolation—the exception rather than the rule. We need opportunities, both physical and virtual, to wrestle with common questions and to share what’s working. As the conversation about equity continues to expand, I hope we see such spaces created in the near future.

Photo courtesy of Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action. CC BY-NC 4.0.