Technology Tools

Edison, the Science of Sustainability, and the Value of Invalidation

Topics

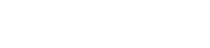

Educators often take advantage of educational technologies as they make the shifts in instruction, teacher roles, and learning experiences that next gen learning requires. Technology should not lead the design of learning, but when educators use it to personalize and enrich learning, it has the potential to accelerate mastery of critical content and skills by all students.

This blog is the fourth in a series of posts reflecting on a recent gathering of Wave II grantees.

In early December, I had the honor of spending a few days with the Next Generation Learning Challenges Wave II grantees. I joined them at their Capstone Convening in Atlanta, where project sustainability was our focal point.

I was so impressed by the smart and dedicated folks I met at the convening. Some came from startups and some from research groups at universities, but all were educators above all else. Entrepreneurship and academia both have cultures focused on success (even more than other domains), so it is noteworthy that the 19 grant-winning organizations convened had been identified 18 months prior as the most successful applicants from those already competitive domains. Moreover, in times when education dollars are often scarce and stretched, winning funding can be particularly challenging. But these grantees succeeded in winning funding for their tech-enabled learning modules, surely only the latest wins in careers (and likely entire lives) littered with successes.

And this can be a problem.

See, smart folks—really, really smart folks—aren’t used to failing, so they’re often terrified of it and just don’t know how to fail. But failing can be good for business.

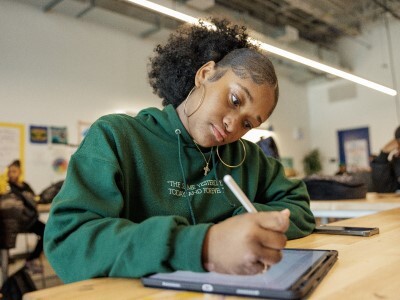

A quotation commonly attributed to the late, great inventor and entrepreneur Thomas Edison has made its way to nearly every corner of the internet:

“I have not failed. I have just found 10,000 ways that do not work.”

For the sake of this conversation, let’s just assume the attribution to Edison is correct. I’ve heard or read the quip countless times, each time a slight variation on previous incarnations. What remains consistent is the lesson it would share.

In the axiom, many would see Edison the businessman and take the epithet to promote perseverance. But remember that Edison was also a scientist, and imagine the storied inventor running his experiments as you reconsider the quip. I offer three guiding principles to keep in mind as you do so:

1. All projects consume resources.

The simple fact is that innovation of any kind requires time, energy, and money, so ignore any mental distinctions you may have made between for-profit businesses and not-for-profit organizations. Whether you intend to build a new technology, develop a new theory, or offer a new service, you’ll need the time and energy of contributors and money to cover your team during development, at the very least. Investor capital and grant funding can be great (and may be necessary at the outset), but both rely on external factors.

Particularly in mission-driven fields such as education, the only real differences between for-profit and not-for-profit entities are legal and accounting details. To develop and grow, all organizations need a reliable flow of time, energy, and money. The fewer of those variables left to external control, the greater your chances of success.

2. Put yourselves in the shoes of your funders.

Whether you’re in a startup, a pure research lab, or anything in between, someone funded your project: an investor, a foundation, a university, or maybe some combination thereof. Why? What outcome was your funder hoping to foster? Why did your investor choose to invest in you and not in someone else?

No matter the type of funding, the most likely answer is that funders believed that:

Their capital + your ability to achieve awesome things -> change the world

No investors or foundations fund organizations merely because they enjoy giving out money, and funders aren’t known to pay indefinitely for hobby projects. When folks give you money, they expect (or at least hope for) certain outcomes—outcomes which require time, energy, and money. So becoming self-sustaining isn’t simply a nice goal; it’s an ultimate necessity if your product is to have the impact you and your funders intended.

3. Think of yourself as a sustainability scientist.

There’s nothing wrong with the need to make money; no one will fault you if your organization charges someone for a product. In education, however, many innovators are (understandably) reluctant to charge teachers or students. The good news: you don’t necessarily have to. The bad news: you’ll probably need to find revenues somewhere.

The NGLC grantees, for instance, are already starting to collect valuable information about how learning occurs. What other information by-products are being produced? Other than teachers or students, who might invest in that standardized information?

Just as you might design a more traditional scientific experiment, design revenue experiments. Much like the null hypothesis, first test the question you’re most afraid of being wrong about—your riskiest assumption.

And now, let’s get back to those incredibly smart grantees I got to know a few weeks ago.

Since many of the smartest people I know aren’t used to failing, the experience can be genuinely scary. This often manifests in people testing verifiable facts or minor assumptions rather than allowing themselves to feel vulnerable by exposing their riskiest assumptions to the whims of customers or users…but customers and users are exactly whose buy-in they’ll need to succeed. I certainly saw some of that early on at the convening, but with a little prodding the grantees were quick to understand the analogy to Edison the scientist:

“I have not failed. I have just found 10,000 ways that do not work.”

While I hope the comment also encourages perseverance, I think it speaks volumes about the scientific mindset of the would-be “sustainability scientist.” In a world of constrained resources, it is incredibly valuable to know where not to invest time, energy, or money. A “failed” experiment isn’t a failure at all, but rather solid invalidation of one possible option. It is a lesson on how not to allocate resources in the future.

Invalidating a particular possibility is invaluable on the road to sustainability. Just as each of Edison’s “10,000 ways that do not work” brought him a step closer to the way that does work, every elimination in your sustainability experiments will result in better resource allocation. So don’t think of them as failures, think of them as efficiency lessons that bring you closer to sustainability.

Finally, remember that Edison was equal parts scientist and businessperson. I am convinced the two were interdependent and complementary drivers of his prolific career of world-changing innovation. I know the inspiring NGLC grantees I had the pleasure of working with—and any next gen innovator, in fact—can also achieve great outcomes with a similar combination of the scientist’s perspective and the businessperson’s persistence.