Why Schools Need to Change

A Full Spectrum Narrative of a School for English Language Learners

Topics

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Creating Spaces with Intention for Maximum Impact

Student-centered evidence helps International High School at Langley Park better serve English language learners and disrupts the narrative about ELLs.

At the International HS at Langley Park (IHSLP) where I was the founding principal, we always worked to create a school culture where we valued all students for their varied and unique abilities. I inherently believe that ALL students bring something to the table, no matter how strong or not their education has been prior to attending IHSLP. Students learned valuable skills whether they went to private schools their entire lives or they got most of their education while working in the field.

At IHSLP it was never just about the end-of-year assessments because these state exams could barely tell us anything about where our students were at holistically. There were always layered issues to examining students: At what point do they test without appropriate supports provided to students not yet proficient in the English language? Were these exams culturally responsive to the context and history of the students being tested? Were our students sufficiently technologically literate to find success? Had we considered the full spectrum of evidence that deemed a student successful in our school building?

These are just some of the questions that would go into our annual planning on preparing ourselves and our students mentally to face such a challenge, especially when these exams were not aligned to the way we were engaging students in learning. IHSLP has a competency-based model with underlying frameworks of project-based learning nested in the Internationals Network design approach. IHSLP was designed to meet the needs of English language learners and focuses on receiving learners who have been in the country two years or less. From the beginning, we decided to shift our focus away from these state examinations being the end-all task. We decided to live in a space where all small successes were celebrated in a major and public way while being certain that we were being inclusive as to what we defined as being successful.

IHSLP Graduation 2021 (Courtesy of Prince George's County Public Schools)

Student-Centered Evidence

One of the ways that we asked students to become change agents and to disrupt the narrative of what was being said of them in politically-charged spaces was by understanding and taking ownership of their data. This started with the intake process where we asked students very deep questions about who they were and what they were bringing to the table. We learned so much from our students and their journeys and we learned how to best serve them by asking a few questions: Who did you live with growing up? What is your favorite subject in school? How many siblings do you have? What was school like for you in your native country? Among other pivotal questions, these simple questions helped us to personalize pathways for ALL students.

One of the most important pieces of data we asked about was language level to understand what cohort and advisory would best fit a student’s language and academic needs. Often, students and parents did not really know where students were and we were dependent on data coming from the middle schools, if they had attended, to determine those levels.

Though it was in that interview that we collected this information, students were then charged with charting their language journey via the creation of a portfolio that they would self-track in their English to Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) class. They were given multiple opportunities through a variety of units and themes to improve their portfolios and gather evidence. They would then present their portfolios at the end of the school year to community members.

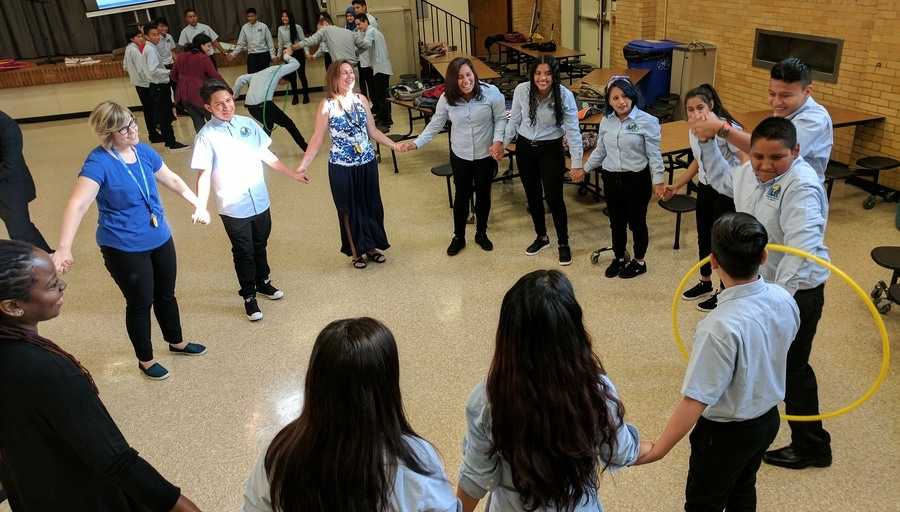

Activities like these at orientation help build the culture and enabling conditions for student-centered evidence. (Courtesy of the author)

Enabling Conditions for Student-Centered Evidence

While in ESOL class, students collected and charted their own evidence while adding a variety of pieces of that evidence into their portfolio. Just like adults set goals, we had our students set annual goals for their language growth aligned to the school’s annual goal (yes, we actually shared with students the schoolwide goals that adults were working on). This was all fueled by our “one learning model for all” motto as part of the International’s HELLO principles. By sharing these schoolwide goals, students found more investment in their “why” and shared a collective vision in which they were empowered to support the school community while working on their own language growth. In some way they saw how their footprint in the short timeframe they were with us would impact the school environment, leading to a culture of openness, honesty, and collaboration that resulted in increased language capacity and academic growth through content, critical thinking, and social-emotional skills.

Part of the journey was also making sure that, while we valued native language, we exposed students to English as much as possible. When students came to all office spaces, we spoke to them in English. After testing out Reading Plus for effectiveness in our community, we engaged students in this language program to help them improve their reading comprehension. While ESOL teachers held the language growth process, the entire school was invested in this language growth. Everyone in their capacity as advisors had a role in helping kids keep track of their language growth and giving meaningful feedback to students on how to improve. They based their feedback on professional development curated by the ESOL and ELA departments.

We also created spaces where students would contribute to the work happening in the adult spaces. For example, we asked students to volunteer to give feedback on the language competencies that were created when the school opened. Our ESOL teachers were noticing, as they tested these competencies in their classrooms, that some of the processes for assessing language were not aligning to how students were internalizing and receiving feedback on the competencies. One of our teachers was empowered to develop a process of co-revision of the language competencies and invited any student that wanted to participate as part of an after-school initiative. Through this engagement, students not only gained a sense of ownership over the language competencies, but also helped shape one of the ways that we measured success in our building.

Lastly, we knew as a school that just doing the work ourselves would not have enough impact in the way that we were engaging students in their language development. We decided to connect with and build the capacity of our feeder middle school teachers, counselors, and administration. We shared some of our strategies with them and we had them see it in action through classroom visits. These efforts led to discussions and partnerships that helped to elevate student voice at the middle school level and also helped to prepare them for a high school journey unlike any other at IHSLP. We moved from a local investment of empowering students through a lens of equity to a justice-oriented mindset. We began creating a movement to help enable other adult learners and students to disrupt the traditional and deficit-centered beliefs on what ELL’s can and cannot do.

Ultimately, we created an environment where we valued the #FullSpectrum of evidence that led to a holistic understanding of IHSLP students and their growth. We created the conditions for the students that we served and those that were being prepared to attend IHSLP by offering capacity-building opportunities that extended beyond the adults and spoke to our “one learning model for all” model. It was these convictions, among other practices, that helped us create an environment where we leveraged the student voice to improve all aspects of the school.

About the Full Spectrum of Evidence: To help young people develop into high-functioning adults, we need to work with—and value—the full spectrum of evidence that demonstrates their development. NGLC's Full Spectrum of Evidence project provides a framework, toolkit, and student-voice gallery to help schools and districts use both “system-centered” and “student-centered” forms of evidence of student growth effectively. Read the project announcement and explore the Full Spectrum toolkit.

Photo at top courtesy of International High School at Langley Park.