An Educator’s Guide to Learner Profiles for Students

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

As more and more educators work to replace factory-model schools with personalized, student-centered learning experiences, knowing our students has taken on new meaning.

In this edition of the NGLC Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, we consider a more profound kind of knowing our students, and its role in personalizing teaching and learning, by answering these questions:

- What is a learner profile? What does it include?

- How can this information support deep, authentic, and more personalized learning?

- How do I create learning profiles of students?

- What resources do we, as educators, have at our disposal?

- How can the use of learning profiles increase student achievement?

Deepening Personalized Learning

“If we really believe that teaching is about the student, then it sure would help to actually get to know the students in deeper ways.”

This statement by Emily Puetz, the learning architect at ReSchool Colorado, sounds a lot like common sense, but it is not as common as one might think.

In the past our data about students has been narrowly defined. At the start of a school year, educators in diverse school settings are examining student test scores and other achievement data to understand where students are relative to grade-level content standards. Valuable conversations about fragile or missing skills are taking place, informing decisions about student placement and interventions needed to support academic success.

Educators in next generation schools, however, are guided by broader definitions of success and a set of forward-thinking competencies—the knowledge, skills, and habits students will need not only to survive but to thrive as adults. Competencies that engage and develop learners into innovative problem-solvers and risk-takers who explore diverse points of view for ethical decision-making and positive impact, and other competencies as described in the NGLC MyWays Student Success Framework. Unfortunately, in most schools, data on dimensions other than academic achievement do not pop into a teacher’s data dashboard or arrive in a digestible report from the district.

This is where the learner profile, sometimes called a learning profile, comes in. According to Education Reimagined, a personalized learning approach also considers “such factors as the learner’s own passions, strengths, needs, family, culture, and community.” As a first step toward charting a student’s personalized pathway, the learner profile encourages a fuller understanding of who each child is. For example, Emily rattles off a list of just some of the information ReSchool’s Learner Advocates might collect about the children they serve: learning styles, what they are curious about, what motivates them, social-emotional needs, challenges, even the ideal noise level of the learning environment. Profiles can also include character and leadership traits like gratitude, optimism, and self control or student work products, like a “personal best” portfolio.

In his TED Talk “The Myth of Average,” Todd Rose advocates for a more flexible learning environment, one that rejects the notion of the “average student” and honors young people’s individuality—what he calls their “jagged profiles” of strengths and interests, as well as weaknesses. Personalized, student-centered learning aspires to do just that.

What is a Learner Profile?

From elementary school to high school, a learner profile is a way for students to describe themselves both as a person and as a learner. Learner profiles provide a space to gather information beyond student test scores and achievement data to create a full picture of a student. With learner profiles, students are invited to share a well-rounded picture of the gifts they bring to the classroom and explain what they need from their school, teacher, and others to help them be successful in their learning.

When I talked to next gen educators, they told me what was most important about learner profiles: that students get a chance to express themselves and know that people in their school are listening and truly want to know them. As Emily at ReSchool Colorado shared, the tools themselves are useful, but the conversations about “this is me and this is what I love” that happen in tandem are what matter most.

The specific information that is collected in a learner profile varies across schools, and even across grades and classrooms. Learner profiles may include any of the following information about a student:

- Background information on their family, culture, and community

- Academic strengths, knowledge, skills, and samples of their work

- Leadership and character traits

- Other gifts and unique potential

- Learning style and motivation

- Passions and interests as well as what they don’t like

- Goals and dreams

- Academic, social, and emotional needs

- Challenges and what they struggle with in school

- Their best environment for learning

Key Learning Profile Attributes

Creating learner profiles and engaging in conversations about them can help learners better understand themselves. It can help parents, teachers, and other educators better understand their students.

And with the following attributes, a learner profile can help students, families, and schools work together to deepen personalization, change instructional practices, and help students reach their own success goals:

- Created and owned by the learner

- Describe gifts as well as needs, challenges as well as opportunities, both likes and dislikes, and everything in between

- A hub for communication between learners, families, and educators

- Dynamic, changing as the learner grows

- Avoids pigeon-holing a learner that could limit them from discovering new interests, growing academically, or personal development of new skills and strengths

- Celebrates the diversity of learners’ identities, such as English language learners, recognizing how their background can help them succeed.

Learner Profile Templates for Teachers from CICS West Belden

At Chicago International Charter School (CICS) West Belden, learner profiles are designed to go beyond academic performance and help students explore who they are, how they learn best, and what motivates them. These profiles give teachers valuable insights to personalize instruction and build stronger connections with each student, supporting both academic growth and essential life skills.

To support this work, CICS West Belden offers printable learner profile templates and a student profile template for teachers designed for:

These learner profile posters and templates help teachers gather meaningful insights into each student’s:

Academic strengths and areas for growth

Passions, interests, and dislikes

Learning styles, strategies, and environment preferences

Social-emotional needs and character traits

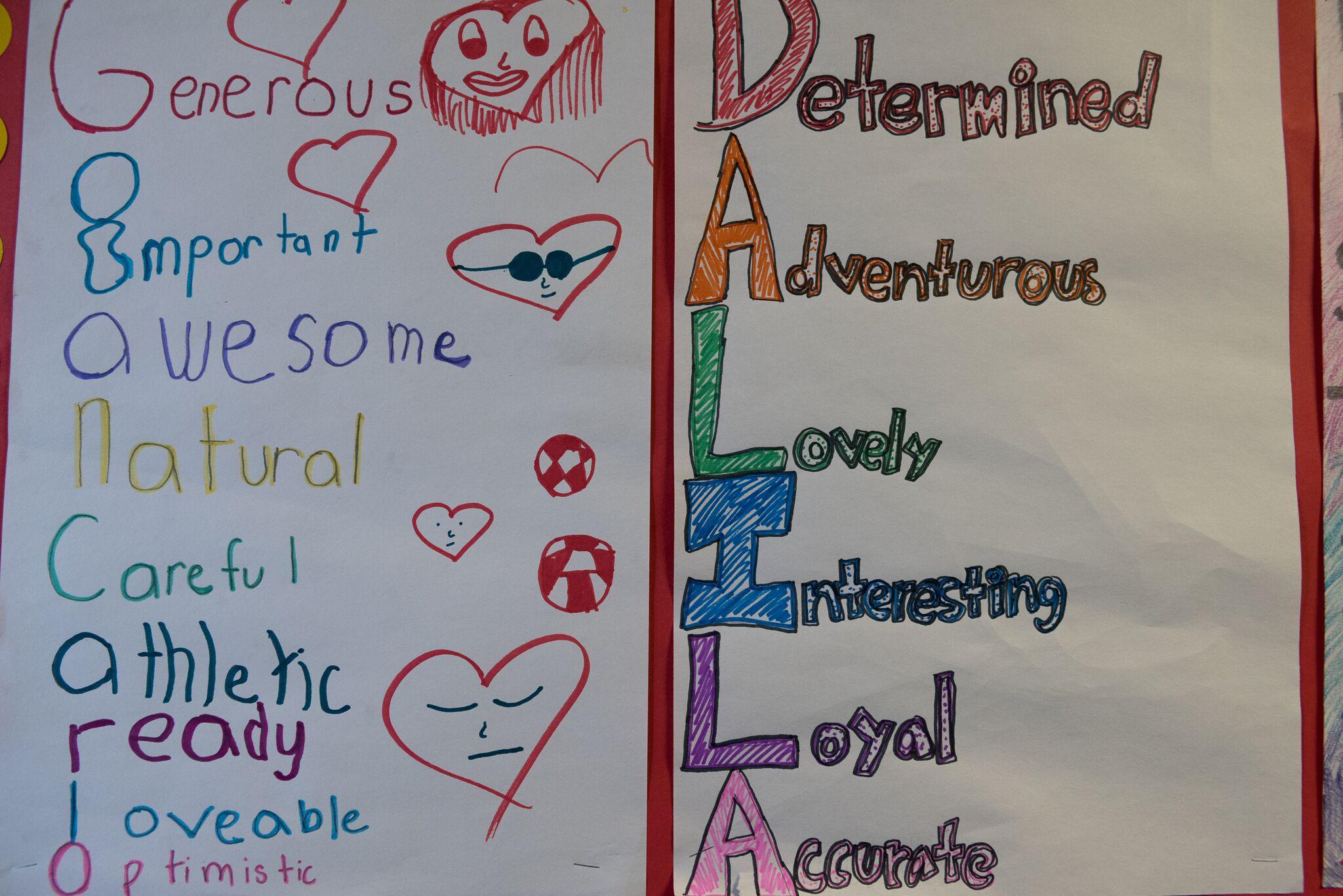

The poster project (see example above) also invites students to explore and express their character, encouraging self-reflection and helping build a stronger classroom community.

Whether you’re launching the school year, planning lessons, or guiding goal-setting, these student learner profiles provide a practical way to understand and support individual student learning. They can also be used in professional development sessions as models for implementing personalized pedagogy.

While originally created for elementary grades, the ideas behind these templates can be adapted for middle school learners as well, with appropriate modifications to match students' skills and developmental needs.

Creating Learner Profiles

Learner profiles may exist as Google or Word documents, presentation slides, posters, portfolios, performances like spoken word poetry, videos, or other multimedia creations. Teachers sometimes use one of these formats for all students, and sometimes students choose what format they want to use.

To support students’ self-knowledge and ownership of their learning, the members of the NGLC community I spoke to include the students and their parents in conversations about strengths, interests, and learning goals. Interviews, data conversations, and student-led conferences all provide a forum for building—and building on—a fuller and more nuanced profile of each learner. Surveys, inventories, and guided prompts are also useful ways to gather information from students.

Schools often use tools that they create themselves, but they also adapt tools from other schools or purchase tools to help them collect and present information for learner profiles. As engagement with next generation learning grows, so do the number of tools and techniques educators, students, and parents have available to co-create a robust learner profile.

Many tools are relatively low-tech and free. Options for older students include free online tools like Learning Heroes Character Strength Finder and Thrively’s survey of strengths, interests, and aspirations, both of which are used by ReSchool to match high school students with out-of-school experiences aligned to their goals and passions.

Other schools support adults to know their learners and learners to know themselves with human-centered, low-tech practices that feature observing, listening, and mentoring like Responsive Classroom’s Morning Meetings, Summit Public School’s one-on-one mentoring program, and, for older students, story-telling and listening circles derived from the Ways of Council.

Using Learner Profiles in Personalized Learning

Administering interest inventories and collecting other types of student information are not new practices. For decades educators have used tools like this to help build strong relationships with their students and even to support differentiation. What’s different about the learner profile is the ways it is used to set a personalized, student-centered pathway toward student-selected goals. In a personalized learning environment, educators offer choices, and students, over time, make more of the decisions about what, how, or even where they will learn.

Barbara Bray and Kathleen McClaskey, co-founders of Personalize Learning, LLC, make this connection between the learner profile and student choice very explicit in their article, “Personalize Your Learning Environment.” Drawing upon Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, they urge educators to provide options for how students access, engage with, and express their learning. Through making choices and exercising agency, students can acquire the skills and executive function they will need to direct their learning, careers, and lives as adults.

In addition to empowering students to make choices about their learning environment, learner profiles are a key first step for student goal-setting and designing a personalized learning plan (PLP) to achieve them. As Emily observes, “There are a lot of tools out there, but it matters less what the learner profile is and more about how it is used—it should be the starting place from which we build and match learners to learning experiences.” In Vermont, which has engaged with personalized learning for over 15 years, all students co-create a PLP (with parents, educators, and advisors) no later than grade seven. Their student-facing framework explains the dynamic process of creating a learner profile, setting goals for college and career, and establishing a plan to reach them, as well as opportunities to reflect and revise.

This evolution from learner profile to student-owned pathway is key at Building 21 (B21), a competency-based model with high schools in Philadelphia and Allentown, Pennsylvania. At B21, students are referred to as designers, and much of the learning along their pathway occurs in project-based studios and intensives tailored to their interests and career goals. Tom Gaffey, chief instructional technologist for B21, stresses that theirs is a work in progress, but he invites us to “imagine a time where designers are picking their studios every 10 weeks by what they are most passionate about, what competencies they need, and what’s currently available.” To offer this degree of student choice and agency, B21 challenges many of the traditional notions of what school is and can be in order “to create a model that breaks down time-based, grade-based, place-based structures so personalized learning can thrive.”

Using Learner Profiles to Change Instructional Practices

All of the educators I interviewed spoke to the dynamic nature of the learner profile. Next gen educator Sherre Vernon recommends that educators “be open to surprises about students’ strengths and how much these can change.” Emily, too, cautions against pigeonholing students based on their profiles. “It’s not ‘this is who I am, full stop.’ Each experience informs, sparks, or uncovers new interests.” Even though it will change, doing the work of creating a learner profile is worthwhile, she argues, because it is “an opportunity for students to express who they are and to work in their sweet spots from the start.”

The parting advice from our educators is this: just as learner profiles evolve over time to support personalization at the student level, so should their schools and the entire learning ecosystem. If students are to move from self-awareness to exercising agency, the learning environment needs to transform to provide opportunities for self-direction and real choices, not trivial variations along the lines of “canned peas or frozen peas?”

To Kendra Rickerby, founder of Revivify Learning Systems and Vermont’s former co-lead to the New England Secondary School Consortium, this means prioritizing systems thinking as a prerequisite to changing instructional practice. It also means making a serious commitment to supporting students to take responsibility for their learning. Products like learner profiles and pathways serve as useful hubs for communication between educators, students, and parents, she says, but “if the shift to personalization is just creating more work for adults, then the way you are implementing personalized learning needs to be rethought.”

For Rui Bao, head of data and new schools for Caliber Schools, technology can foster an environment that is personalized but not overly burdensome for educators. At Caliber, she says, “we are constantly looking to strike the right balance for teachers: providing enough automation so that creating the learner profiles and pathways doesn't overwhelm them, but still allowing space for personalized, qualitative insight.”

Based on his experiences at B21, Tom calls attention to a school’s system of structures and policies, comparing it to a planet’s gravitational pull. “Your policies can impose limitations and be like Jupiter,” where educators are so burdened with limits that they cannot move freely enough to personalize learning. A better alternative, he argues, one that realizes the unique potential of each student, is to remove structural constraints and “be like the moon, where you—educators and students alike—can jump as high as you want.”

Additional Resources

Here are some other learner profile tools and resources referenced by the educators who participated in this story:

- Transforming Education Mindsets, Essential Skills, and Habits Resources: This collection of tools, research, and webinars provide information about MESH assessment and development based on their work with an extensive network of partners.

- Learner Profile Tools: This table lists the tools ReSchool Colorado’s Learner Advocates can choose from to begin matching learners to experiences based on their knowledge of individual learners, their interests, and their family context. Organized by age range, the table describes the tool, how long it takes to administer, and provides recommendations for optimal use.

- Vermont Agency of Education blank template and filled-out version: These tools illustrate how adults and students can use a learner profile to co-create goals and personalized learning pathways.

- Indigo Assessment: Available for both middle and high school students, this assessment provides learners, parents, and educators with a unified report with information in four domains: 21st Century Skills (strengths), Motivators (passions), Behaviors (personality and communication), and Value to a Team.

- The Learning Genome Project’s Learning Style Preference Cards: These cards can be used to facilitate one-on-one conversations between children and adults about who they are and how they best learn.

- CliftonStrengths: Based on positive psychology and originally designed for adults, StrengthsFinder can be used at the high school level to identify strengths and talents in 34 areas or “themes;” these themes serve as a foundation for strengths-based learning and development.

- HIGH5: This strengths test is designed for adults but free to complete and discover an individual's top five strengths: “what you are great at, what you are energized by, and what gives you a sense of meaning.” A student strengths report is available for a fee and strengths focus on academic superpowers, working in groups, and future pathway recommendations.

Related Posts

- Learner Profiles and the Progression of Personalized Learning - Follow the journey of CICS Irving Park teacher Claire Kreller as she used learner profiles in her second grade classroom from 2014 through 2020, with advice and resources.

- Student Goal Setting - No real personalized learning model can flourish without student goal setting as a foundational activity. Here’s why.

- Leadership Habits, Genius Hour, and Learner Profiles in Colorado - Schools across Colorado are shifting to more personalized learning by starting with Steven Covey’s Habits of Success, the IB Learner Profile, and Google’s Genius Hour.

Photo at top by Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages, CC BY-NC 4.0. This article was first published in October 2017 and updated once before in May 2023.