Building Community

Healing and Re-Humanizing Our Education System

Topics

When educators design and create new schools, and live next gen learning themselves, they take the lead in growing next gen learning across the nation. Other educators don’t simply follow and adopt; next gen learning depends on personal and community agency—the will to own the change, fueled by the desire to learn from and with others. Networks and policy play important roles in enabling grassroots approaches to change.

How might we heal our way to a deeper kind of learning and definition of success for each and every student and adult in our educational system?

“The work of coming back together and remembering is often easier said than done. It will be inevitably difficult when hierarchy and separation is convention. In our outcome and results driven world, it is easy to keep our eye on tomorrow without attending to what is happening today. To that end, refocusing our sight on ourselves, how we move in the world, and the relationships we build and nurture is the keystone of equity centered improvement, design, and innovation.”

–Caroline Hill, “How to Walk Through Fire”

Four years ago, at the first convening of the Deeper Learning Dozen, at Harvard, after a brief welcome to the assembled school district leadership teams from my co-director and colleague, Jal Mehta, I found myself saying, with a sentence stem we had learned from the National Equity Project, “If you really knew us, you would know that… We are about healing, healing from the toxic effects of a dehumanizing bureaucratic system of education that we have all of us, students and adults alike, inherited and lived in for far too long.”

I was thinking about Max Weber’s statement from the late 19th century: “Bureaucracy develops the more perfectly, the more it is 'dehumanized,’ the more completely it succeeds in eliminating from business love, hatred, and all purely personal, irrational, and emotional elements which escape calculation.” I realized how damaging such a dehumanized system has been to us all in education. So I also quoted from adrienne maree brown that morning:

“If love were the central practice of a new generation of organizers and spiritual leaders… we would see that there is no such thing as a blank canvas, an empty land or a new idea—but everywhere there is complex, ancient, fertile ground full of potential. We would organize with the perspective that there is wisdom and experience and amazing story in the communities we love… we would want to listen, support, and grow… we would understand that the strength of our movement is the strength of our relationships, which could only be measured in their depth. Scaling up would mean going deeper, being more vulnerable and more empathetic.” (emphasis added)

Since then, we’ve struggled through two plus years of COVID. We awakened to the deep need for racial justice, and we started to reckon with the devastating effects of colonialism on the peoples who were here before European settlers (as well as on all of us whose minds, hearts, and spirits have been colonized). Healing and re-humanizing our education system has become even more urgent.

The Deeper Learning Dozen community of practice met again in person for the first time in over two and a half years just a few weeks ago. We prioritized coming back together, reconnecting, and relationships before our adult learning “curriculum.” We were graciously hosted by the Semá:th people, in their Longhouse, on their unceded ancestral lands along the Fraser River, in what is called in colonial terms, Abbotsford, British Columbia, and is home to one of our school district members. The Longhouse Keeper and several elders and knowledge keepers led the opening ceremony, welcoming us with song, drumming, and storytelling, and appointing witnesses, whom they asked to pay attention because they would be called on to reflect on what was happening.

Courtesy of the author.

We asked our members to bring a meaningful personal artifact to share with others. After sharing the stories of those artifacts in pairs and quads, they built a sculpture out of them in the center of the Longhouse. This storytelling was one way for our DLD community to move from welcoming people’s individual identities to creating a collective “we” that can more powerfully act in the ways brown describes. The activity both confounded and delighted those who had not before had the experience—either in their own organizations or in an educational gathering—of valuing personal storytelling and the power of connection over a mechanistic approach to technical problem-solving. As Josh Schachter of CommunityShare says, “Some people say the shortest distance between two people is a story.”

We next sent people on walks together in reconfiguring random pairs and asked them to share various aspects of their professional identities and the equity and deeper learning work they had been doing. We challenged them to be together as learners, not performers, and to genuinely and authentically engage in the conversations that were possible at this time with these people, conversations that matter.

This is not “soft” work; this is the hardest work there is, because it is healing work. It is the work brown describes that helps us see in ourselves the “complex, ancient, fertile ground full of potential,” and that each of us already brings “wisdom and experience and amazing story [from and to] the communities we love.” We deliberately designed these activities so everyone present could experience how we might all live and work together if we took healing seriously. How might we heal our way to a deeper kind of learning and definition of success for each and every student and adult in our educational system?

This is not “soft” work; this is the hardest work there is, because it is healing work.

But OK, we can do this in a convening, a place bounded in space and time, whose intended purpose is clearly set out in our values and principles, and that our community of practice members have come to expect from us as designers and holders of space specifically for these kinds of experiences. But how do we heal our education systems?

I look to Margaret Wheatley for one answer. She says it most succinctly:

“To create better health in a living system, connect it to more of itself. When a system is failing, or performing poorly, the solution will be discovered within the system if more and better connections are created. A failing system needs to start talking to itself, especially to those it didn't know were even part of itself.”

On Wednesday of our week together, we spread out across the school district to witness how Abbotsford is healing by creating better connections within itself. Some of us listened to a kiva panel of middle school students answer some really challenging questions about their experience of school. These were not the usual suspects we invite into the conversation when outsiders visit our schools; they were the kids most usually left out of the conversation, whether because of being Indigenous, or because of ethnicity or race, sexual orientation or gender identity, or coming from poverty or extremely challenging living situations. And they were astoundingly genuine, honest, frank, articulate, and confident in what they shared. Their message was loud and clear: “Prioritize relationships and belonging over academics… Prioritize relationships and belonging over academics… Prioritize relationships and belonging over academics…” They all identified at least one adult in their schools with whom they felt connected and with whom they could discuss anything. Yet they felt that beyond those individual relationships, there was much healing to do in other classrooms and the broader environment of school.

Reflecting on what we had heard from the young people, Carla Danielsson, an assistant superintendent in the Abbotsford School District, said, “Health, well-being, and belonging are fundamentally pedagogical issues. It’s not about putting posters on the walls.” That is, the teacher must create a safe and welcoming learning space particularly for our most marginalized and vulnerable youth in order to make the risk of engaging in challenging academic work accessible and possible. And that takes skill and deliberate planning, observation and reflection, and replanning. It’s ongoing work. The dynamic of young people interacting in a welcoming, rich, and demanding learning space is ever-changing and ever-developing.

“Health, well-being, and belonging are fundamentally pedagogical issues. It’s not about putting posters on the walls.”

–Carla Danielsson

Responding to that complexity is deep pedagogical work. But it is not just the work of teachers.

I asked my wife, who teaches English in a public high school where we live and is always a great source for what students and her colleagues are thinking and feeling, what healing meant to her. She thought for a moment, and said, “You know, our kids missed a whole year and more of being in a school building and classroom environment, and this year I can tell you they are feeling disappointed and heartbroken to come back and see that nothing has changed. Somehow, they thought, this would be an opportunity for us to learn how to make school better for them, and it seems instead that we have come back to pretty much the same old and unhealthy routines and systems.” Of course, many teachers worked extremely hard this year to rebuild a healthy culture in their classrooms, and to incorporate some of what they learned from a year away from normal school routines into their renewed practice, but overall not much seems to be different. She added, “We need time to rest, we need to pause… We need to reimagine systemically. The profession overall needs to be more widely respected, and for that to happen, we need to attract and retain better teachers, but that isn’t going to happen without adequate compensation and sustainable work lives. We need way more cross-pollination. We are so siloed. We need more opportunity to learn what’s working well in other places. These take time and money. We need more time for kids and teachers to be out of the building, and interacting with other adults in apprentice-like situations. These all take more flexibility in the way we structure and schedule school.”

So, to reiterate, healing our education systems is not just teachers’ work. Again citing Schachter, “In a healthy [robust] learning ecosystem, everyone is a steward.” To meet the challenge that students have put before us, school districts need to create the spaces where adults can collectively learn, develop, and share their developing expertise in this approach to pedagogy with each other. If we want our young people to experience the kind of connection and deeper learning they are clearly asking for, then adults need to experience that kind of connection and deeper learning together also. Systems must support that work. But this is not the way our districts have been organized, nor the culture we have created in them. The healing systems we need must be brave spaces. These take courage to create and courage to engage in.

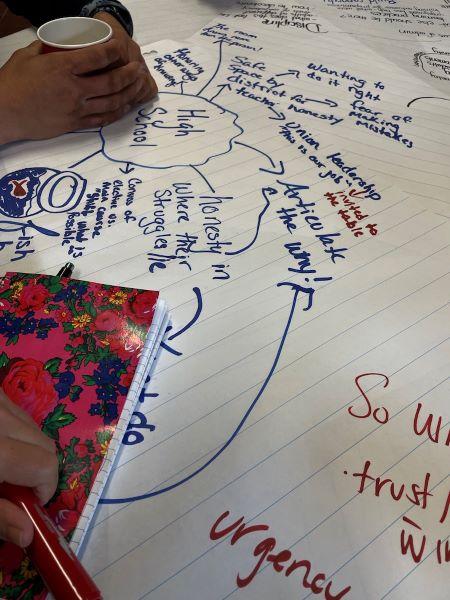

Courtesy of the author.

Many people who could help us create the adult and youth learning spaces we need are already among us, as Wheatley says. We just need to listen thoughtfully. Some of the expertise that already exists includes:

- Restorative justice practices, circles, mindfulness practices, trauma-informed practices, and practices that embed social emotional learning skills in academic work all help.

- The folks at Engaging Schools have inverted the tiered systems of support interventions model to foreground classroom practices that generate a positive classroom culture as well as respond to immediate needs of students.

- The Community Schools model broadens the engagement of the community in raising young people to be healthy adults in a healthy community, which teachers cannot do alone.

- Some districts have worked to redesign systems and structures to flatten their hierarchies, move folks back to directly supporting school leaders and teachers, and shift cultural patterns to provide support and remove barriers instead of monitor for accountability and control for compliance.

And beyond all these examples, there is what we can increasingly learn from other worldviews—ways of being, ways of seeing, ways of knowing, ways of acting, and value systems—that we have traditionally silenced and erased. These worldviews have powerful messages to offer an educational system’s approach to learning and organization that for too long has been dominated by colonialist, White western, mostly male, views, attitudes, and structures. Just as our members experienced in Abbotsford, Indigenous scholars and knowledge keepers across the world are offering their traditional ways for us to learn from. Are we paying attention?

One new member of our community of practice reflected that telling stories about your identity and what matters to you, and hearing the stories of others, is not something we normally do in our traditional bureaucratic systems. The dehumanized spaces, the fragmentation, balkanization and siloing, the constricted and purely technical information flows, the command and control power structures, the mechanistic ways we batch-process students and so also batch-process adults—these all interact to mitigate against connection and relationships and meaningful interactions around equitable deep learning. We don’t need an education bureaucracy that is toxic and dehumanizing. If we recognize what we have been doing, we can see the pain and suffering it causes and act to change it.

****

We have all been called to be witnesses, but we have not been paying attention. We have not been good stewards of the learning ecosystem for our young people. Nor have we been good stewards of the social and political ecosystem, nor the natural ecosystem of the earth. We have polluted and poisoned the waters, and they have made us sick (another story the Semá:th Longhouse Keeper told us). Our young people, whom we should have been stewarding into their development as whole people—bodies, minds, and spirits—ready to take their place in the lineage of stewards, tell us that they are disappointed and heartbroken.

The Semá:th ceremony we participated in during our Deeper Learning Dozen convening was not just about welcoming. The ceremony was pedagogy, a pedagogy of relationships before problem-solving, a pedagogy of passing along the knowledge of our awesome responsibilities as stewards of our learning ecosystem, and the ceremony was a pedagogy of healing and belonging. The ceremony reminded us that “everywhere there is complex, ancient, fertile ground full of potential.” The ceremony reminded us “that there is wisdom and experience and amazing story in the communities we love.” The Semá:th stories, often told as metaphor, reminded us of who we are, asked us to reconnect with our ancestors, with ourselves, with the land, and with our purpose. They reminded us to bring our whole selves into the work, body, mind, and spirit, and they called us to pay attention, and to do the work. Let’s do the work.

Photo at top courtesy of Pixabay.