Reimagining Assessment

Learner-Centered Assessment: Grading for Competency

Topics

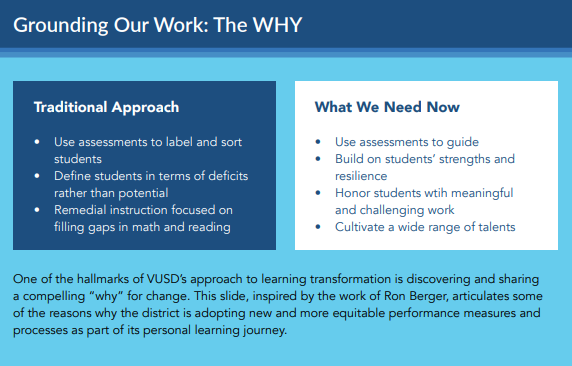

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

Redesigning grading systems to be more personalized, equitable, and standards-based is a major undertaking. These educators are working to figure it out.

“When Mr. Chodola gives us options to revise, I feel like it’s not just, ‘Oh, you got this grade, now move on to the next.’ You can actually have a chance to go over your mistakes and fix them and see improvement in your writing or an assignment that you didn’t do too well on. You get a second chance in this. And I feel like it really has improved my writing.”

–Megan Luck, Grade 12 Student, MVHS

The process of exploring what equitable, learner-centered, and personalized assessment and grading practices could look like at Mission Vista High School (MVHS) began years ago. From the first years of our district’s “Personal Learning Challenge,” innovative teachers—or “cannon-ballers” as we like to call them—had piloted new ways of assessing and grading in their own classrooms.

However, new mindsets and practices have caught on like wildfire in light of COVID. We all learned what the limitations were in terms of engaging students and also about students’ ability to show us what they knew in extremely unusual circumstances.The teaching and learning challenges posed by the pandemic lent themselves well to taking a standards-based approach to grading.

Rethinking assessment and redesigning grading systems is a major undertaking, one that will take time and collective effort. We do not claim to have this aspect of our school’s personal learning model figured out, but we are finding our individual and collective “why’s” to do this work and we are discovering how to accomplish it.

Competency as the Goal

“In math, you have to know A to get to B. You can’t be successful with this concept, this idea, if you don’t understand how to do something prior. And so a lot of times when students start to have that negative emotion about their ability in math, it’s because they got stuck at this one idea or this one thing, and now they’re stuck and everybody else has moved on. And so they just give up, right? That’s where a lot of students are in math. They’ve just given up. I want the students to be more like, ‘Okay, let’s just try this out. Let’s go for this.’”

–Stacy Eyton, Math Department Chair, MVHS

Although standards-based grading looks different based on the subject or context, all of our educators who are piloting this approach share a commitment to assigning grades that accurately communicate to what extent a student has learned essential content and skills, rather than reflecting completion of tasks or the quality of initial attempts. A standards-based approach focuses on constant feedback in the moment as well as opportunities for students to show us their learning in iterations. The final iteration—that last demonstration of learning—is going to be the mark that students earn in terms of how they have, or have not, reached these standards or these skills.

Math teachers at MVHS have led the way in adopting standards-based grading. Stacy Eyton, the chair of the department, was one of the first cannon-ballers with respect to redesigning grading, in part based on her own experiences as a student. As she explains,

“Even in math, it always took me a little bit longer to understand something. I thought about math a little bit differently, or I needed more time to explore something to truly understand it. And so I really value that we don’t reach the same destination at the same time, and we all take different routes to get to that destination.”

Stacy’s first steps in the direction of standards-based grading focused on assessments, offering learners multiple opportunities to demonstrate mastery by retaking tests. She piloted this approach with a small group of students, using two gradebooks—one traditional and one standards-based—in order to perceive the effect on their grades. “I was looking at growth over time with their assessments,” Stacy recalls, “and if they were tested on something the second week and they didn’t get it, I tested them again, maybe five weeks later. I rewarded them for showing me that they understood it. I really saw the difference it made. If they didn’t get it one day, maybe next Monday they’ll understand it, and they can have the ability to show it and prove their understanding of it.”

As a result of Stacy’s pilot, one student who had failed math multiple times was able to experience success for the first time. “Just seeing the numbers for that one student,” she says, “told me that this was why I was doing it.”

Teachers in the social science department at MVHS have also embraced a standards-based approach to grading. For example, Robert Chodola, who teaches AP U.S. History as well as the MVP capstone course, focuses on key skills and standards and prioritizes growth and improvement in his grading practices:

“Any of the assessments they do—reading, writing—they can resubmit them. I give them feedback, and they can resubmit it. I’ll regrade it and give them the score if they improve. Standards-based grading is really more accurate for deciding where students’ skills and understandings are. The validity really goes up.”

Reducing Bias and Promoting Equity

As part of work already underway across Vista Unified School District to align assessment to personalized, equitable learning, we are also applying an equity lens to grading practices. Amy Zilk, former assistant principal at MVHS, is co-chair of the Superintendent’s Council for Equity and Anti-Racism. According to Amy, the council—a group of district and school leaders, school board members, educators, parents, and students—is researching standards-based grading as part of its broad mandate to “look at all instruction, all areas and all the aspects of school through that equity lens and make sure that we’re providing students with everything they need to develop to their full academic and social potential.”

Amy says the council “talked about student motivation, what really motivates students and what doesn’t. We took a look at grading practices, and we recommended that our district start the conversations around mastery-based grading.” In partnership with national experts and informed by how districts like San Diego Unified have updated their grading policies, the council is “looking into what it would take to go to mastery-based grading—what the supports, including teacher training, would be.”

For Robert, equity is also at the forefront of reasons to adopt new approaches to grading at MVHS. One inspiration for him was the book Grading for Equity by Joe Feldman, a gift from Nicole Allard, who was the MVHS principal at the time. Although he was aware of the work colleagues like Stacy were doing to transform their grading systems, his reaction at the time was, “That’s great. Maybe someday.”

Listen as Robert Chodola gives his take on standards-based grading and changing his grading to be more equitable:

“And then we got shut down on March 13, 2020,” Robert recalls, “and I had two weeks to do nothing. And so I picked up Grading for Equity and read it in two days, and I said, well, how can I not do this now?” According to Robert, “The book takes a critical look at many practices that we use for convenience as teachers and really dismantles why we use them. Our reasons are not to the benefit of students—they’re to the benefit of us.”

Robert is particularly critical of the traditional practices like rigid deadlines and giving students zeroes for copying another’s homework, which he refers to as “an academic punishment for something that wasn’t really an academic choice. You are telling them that they are flawed and they are irredeemable just like that zero.”

Explaining what he sees as the connection between grading practices and academic integrity, Robert adds, “When work has a rigid due date, and they’re gonna get deducted or punished for it, students end up just copying each other before they come into class or literally in front of you when you are in class. And what do I do as a teacher? Absolutely nothing, because I was just collecting it for completion rather than for them really engaging with it.” Instead, he tells learners, “If you want to take the time to do the learning, then you deserve the chance to turn it in.”

“In terms of equity,” he argues, “standards-based grades are more bias resistant. Whether or not we admit it, we teachers have relationships with students that are better or less developed than others. And we are going to make subjective decisions about students that impact that letter grade in the class. And when you use a traditional percentage-based system, there’s too many ways for that grade to be misrepresented. So instead of giving Johnny a break because you know what’s going on with his grandma, why aren’t these breaks and empathy and understanding just built into your grading systems?” In this way, he says, “Everyone gets the opportunity to do something because everyone’s life is on a slightly different personal track with hardships and successes, progress and setbacks. When you give [all students] opportunities to work and turn it in, they appreciate it, and it really builds trust and respect.”

Student Agency

A key benefit of standards-based grading is that it takes the mystery out of assigning grades because learners know both what they are aiming for and where they stand relative to essential learning targets. For those educators who have adopted standards-based grading in math classes this year, Stacy says, “It is a very daunting task to totally change how you’re grading, and I think that first step for a lot of my teachers has been scary. But then, they’ve seen that, ‘Oh my gosh, this is actually easier. The students know exactly what they need to work on. Exactly what they need to improve on.’”

Moreover, learners also partner with Stacy to set their grades for the course using one-on-one conferences. She and the learners refer to a list of key skills and concepts, examine evidence of learning, and come to a consensus about a grade that represents each student’s “most consistent level of understanding.”

“Miss Eyton does this grading system where she has conferences with students towards the end of the grading period. She says, ‘Based on your work and what you’ve turned in and how you’ve been improving, what grade do you think you have earned? And describe to me why.’ And so everyone got to the conference and they not only bonded teacher-student, but you get to reflect on what grade you’re getting. Why did you actually earn that grade?”

–Liza Anits, Grade 12 Student, MVHS

For Robert, standards-based grading is also motivational. Especially when coupled with student-friendly rubrics, he says, “You give a common language that expresses truly where their skills are with clear language of what it looks like to be more successful. You can give them feedback that zeroes in on where we’re seeing these skills working out or not working out. And when you allow them to do revisions or retakes or redos, it tells them, ‘Here is where you are here, and here is how you can improve your understanding and get to the next level of performance.’”

- LEARN MORE: See this common rubric from the MVHS history department.

We have learned that co-designing assessment with the learners themselves is so important. They will need the support of educators, but students need to co-create the success criteria so that they can take agency and ownership of the learning, and they can self-monitor as they go along. I recommend inviting students to the design table for as many elements of their school experience as possible. My experience has been that students are absolutely willing to share their insight. They want to help the adults in the building improve the learning environment for all students, and they will always—always—impress us with their solutions-oriented mindset. Students want to help us, and they know how; it’s our job to listen.

Learn More about MVHS

Learner-Centered Assessment: Senior Capstones Measure What Matters - Mission Vista's senior capstone project, My Vision Personalized, exemplifies authentic, performance-based assessment aligned to students’ unique strengths, interests, and values.

Explore MVHS's approach to personalized learning in English/Language Arts, social science, photography, and math.

This article is an excerpt from the NGLC publication, Measuring What Matters: Learner-Centered Assessment.

Photo at top of Stage Tech crew for Mission Vista High School’s Rock the Hill concert, by Harmony Rangel.