Learners’ Perspectives on Formative Assessment Culture

Topics

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Four learners and their teacher emphasize the shared ownership of learning that is part of creating a culture that supports formative assessment.

Formative assessment is not so much a skill as it is a mindset that allows you to develop a skill.

–Joe Nelson, 11th grade English teacher, Will Rogers College High School, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Four hundred educators and partners from K-12 and higher education gathered in Coronado, California, earlier this month to rethink the role of assessment for learning, agency, and equity. The inaugural Assessment for Learning Conference, which drew participants from as far away as Kauai, Hawaii, and Bucharest, Romania, was organized by the Assessment for Learning Project (ALP), an initiative led by the Center for Innovation in Education (CIE), Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC), and design partner 2Revolutions.

On Wednesday afternoon of the conference, the Coronet Room, one of the larger conference rooms at the Hotel del Coronado, was packed with people, most of them adults. They filled the chairs, and more stood at the back, because this session wasn’t just about student voice and agency in learning. It was presented by five learners from Tulsa Public Schools—four high school seniors and their 11th grade English teacher—describing their experiences building and living a formative assessment culture.

WestEd, a nonprofit which partners with Tulsa Public Schools, broadly defines formative assessment as “the process by which, in the course of instruction, the teacher and students alike gather and interpret evidence of student learning and plan next steps to meet intended learning goals.”

For this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, I invited teacher Joe Nelson and learners Brian Antunez, Jack Hernandez, Hannah Hoff, and Warnett Waldon to further unpack the definition of formative assessment (FA) by describing their own experiences living a collaborative, learner-centered, formative assessment culture.

Key elements of formative assessment all four learners and their teacher emphasized during their presentation and our subsequent conversation included:

- Collaborative mindset and shared ownership of learning

- The power of peer feedback

- Co-created goals and success criteria

What Is Formative Assessment Culture?

Joe: When I first learned about formative assessment, I thought of it as a mechanical process: I’m going to do these practices, and I’m going to fix what’s broken. Now I know it’s an ecosystem. The culture is one of mutualism, where both the teacher and the learner benefit. Formative assessment is a base, but you also have to have a culture where it’s safe for teachers and students to try something new.

Jack: [In a conference session] yesterday, I illustrated a picture of me and a group of my friends going to a [traditional] class. I put my teacher in the center because he was in power. He would teach us and then he would give a test. Then I drew another picture of a formative assessment classroom. There were four of us in the group, and learning jumped from table to table because there was something I knew but another student didn’t, and she knew something I didn’t know.

Brian: Working together, we can do incredible things, like the men who walked on the moon. It wasn’t just one guy. Working together, there are benefits that are hard to describe. To make FA work, you have to have a safe space for everybody to be equal, have a voice in the class. To me, that’s the most important thing.

(From left) Joe Nelson, Warnett Waldon, Jack Hernandez, Brian Antunez, and Hannah Hoff present at the Assessment for Learning Conference (Courtesy of Joey Cobbs)

How Does Peer Feedback Support Shared Learning?

Hannah: At first, I didn’t like feedback. I didn’t want to share what I was thinking. But that changed when I worked with a particular student and I saw him listening and writing down what I was saying. It feels equal to talk to peers. When you talk to a teacher, there’s a power difference. With peers, there’s a mutuality of gaining knowledge and coming to equal standing. In a class that uses peer feedback, everyone gets more comfortable talking about what they are learning or what they don’t know.

Working with new people also opens up a different type of thought process. You get feedback from someone with different areas of knowledge that you didn’t understand before because you never talked to this person and you don’t know how their mind works. You can reach a different conclusion or maybe the same conclusion, but you get to question yourself and the answer that you came to.

Warnett: When we had assigned seating with kids we’d never spoken to before, it made me open up. When you are with a friend, you have the same thoughts. When you are with someone you don’t know, it opens up a whole new thought. For myself, I want to hear the complete truth. I want to hear about my flaws and how I can become a better person. I think they want the same, so I try to do that for them, too.

Jack: My classmates didn’t all have Mr. Nelson, so I take what I retain from Mr. Nelson and try to bring it into other classes. There’s a student [in another class] who wasn’t really taught formative assessment, so I tried to teach him what I’ve learned. I said, “Let’s go ahead and give each other feedback. Let’s talk to each other, communicate, and let’s build this bond that we don’t have yet, but we can try. As long as we try together, I feel we can get some work done.”

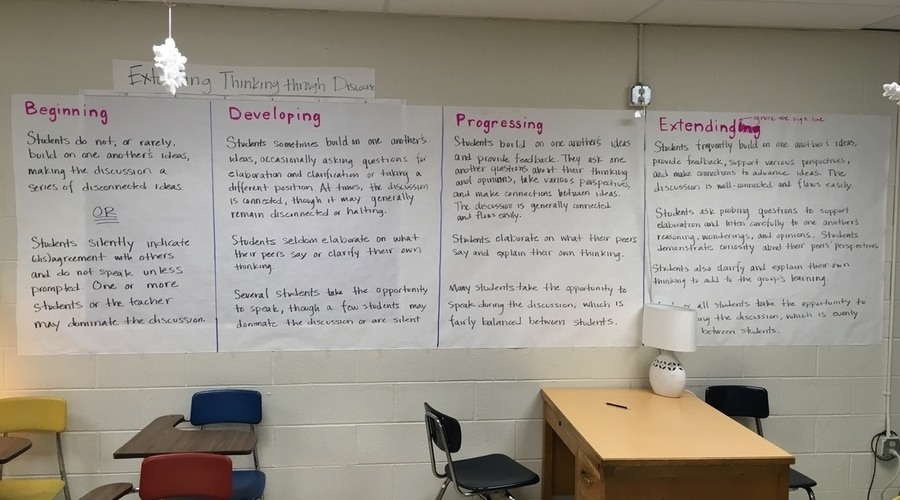

The “wallpaper” in Joe’s classroom describes the four levels of extending thinking through discourse for individuals, groups, and the whole class. (Courtesy of Tulsa Public Schools)

Joe: It’s learning through discourse—every day and all the time. I support them and give them a place and freedom to talk to each other, but they get there on their own. Formative assessment is a journey and a practice, more like yoga. You’ll never perfect it. And you have to build trust. I recently asked for peer feedback from my students on essays I had to write for the district. We can’t ask them to do anything in a classroom that we aren’t willing to do ourselves.

How Do Co-created Goals and Success Criteria Promote Student Ownership of Learning?

Joe: FA is about noticing learning as it is happening in real time and moving from measuring performance to measuring learning. I spend time at the start of the year talking about the difference between compliance and learning. Evidence is visible learning. We have a learning goal for the day, and we do have success criteria, but it’s not a checklist. I co-construct the success criteria with the students. For example, we looked at two paragraphs on the board, and I asked them, “What do you see? Which one is stronger and why?” That’s how we get to the success criteria, and the learners can see it.

Warnett: In the past, in every class it was the same thing. We’d do work and do work and then get a grade. In Mr. Nelson’s class, at first I was quiet and thought I’d just get my work done. Now I ask, “Why are we doing this?” I want to learn, and I want to know why I am doing the work. Having a learning goal and success criteria helps me. I take pictures of the learning goals to keep me on track.

Brian: It’s satisfying and pleasing to reach a goal—we know we have reached something. In Mr. Nelson’s FA classroom, we make our own goals and break the goals down to help us stay on track. You can go really high, but you have to use little steps to reach the goal.

Jack: In the past, maybe you were there for the grade or impressing your parents. Some teachers write the learning goal on the board but never point to it or talk about it. If you break a goal down step by step, you can decide, “Did I accomplish it?” and feel like you actually did something for once in class.

Hannah: Mr. Nelson would direct us to the learning goal and then, at the end of class, ask us if we had learned and accomplished the goals. When students have a voice about what they’ve learned, they get more confident about saying what they are and aren’t learning.

What Advice Do You Have for Educators about Formative Assessment?

Warnett: One thing I would ask my teachers for would be vulnerability, to show that they care about us—to be on the same level and to show they want to be successful and have their students be successful.

Brian: Be at the level of the student, because everyone is learning. You can learn new ways to teach that would be beneficial to students, so have an open mind.

Joe: Transparency is really hard, but it’s where you get the most buy-in—when you’re genuine, and you are a learner.

Hannah: I would ask for more leadership inside the classroom. Even if a classroom is not set up in an FA style, I would then ask, “Where can my voice be implemented in this lesson? Where could other students’ voices be heard? Could you make this a setting where everyone can be comfortable sharing their ideas with each other and be heard?”

Jack: I would ask my teachers if they are willing to learn more about formative assessment. It’s a unique system that honestly brings all of us together like a family. We learn together and we move together toward the learning goals.

Resources

- The Extending Thinking through Discourse Continuum, created by Student Agency in Learning (SAIL), a project of WestED, an ALP grantee, was the source for Mr. Nelson’s classroom “wallpaper” of discourse levels.

- Noticing Critical Shifts, a resource from WestEd shared in Joe and the students’ conference session, identifies several shifts that embody new roles for teachers and students as students become responsible for, and prime agents of, their own learning.

- The ALP Educator Resource Library presents resources, results, tools, practices, and stories about rethinking assessment shared by educators across the ALP network.

- This NGLC story by Tony Siddall describes key elements of WestEd’s SAAL (now SAIL) project, an inquiry into how formative assessment practices—at both the teacher and student level—can contribute to learner agency.

- MyWays Report 12, Assessment Design for Broader, Deeper Competencies, presents the evolution toward greater authenticity and multiple measures, and recommends five assessment strategies to support assessment for learning.

Photo at top courtesy of Joey Cobbs