Learning to Teach by Listening to Students

Topics

Educators are the lead learners in schools. If they are to enable powerful, authentic, deep learning among their students, they need to live that kind of learning and professional culture themselves. When everyone is part of that experiential through-line, that’s when next generation learning thrives.

In this excerpt from the recently released book, Sparks Into Fire, author Young Whan Choi relates a story of how one student's question—“Why didn’t you push me harder?”—shaped his growth as a teacher.

Note: This article is an excerpt from the author’s book, Sparks Into Fire: Revitalizing Teacher Practice Through Collective Learning, available from Teachers College Press.

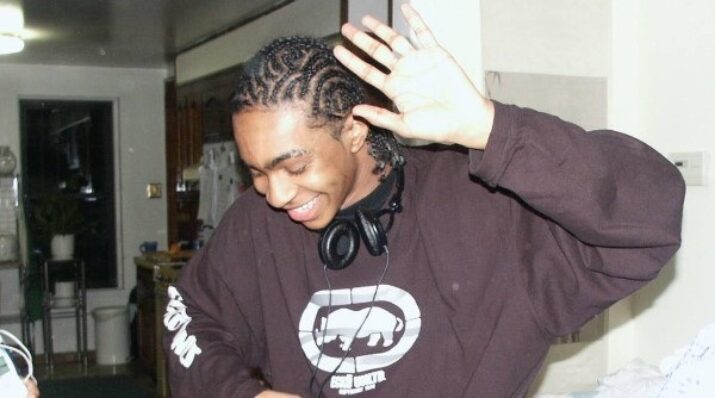

Teachers aren’t supposed to play favorites, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have favorites. At the Met Center, Domingo, or DJ as he was known to us, was one of my favorite students. I met him when he was thirteen, “all bones” as he would say, and full of angst. He would pour his thoughts and feelings, mostly rage and frustration at the injustice of the world, into pages and pages of his journal, which I collected along with those written by all of my students. I related to DJ’s cynical view of the United States’s racial “progress,” and we both loved the lyricism and critical consciousness expressed in the album Mos Def and Talib Kweli are Black Star.

I took his views seriously, feeding him books and music and exposing him to the creators and intellects whom I hoped would both nurture and challenge his budding interest in spoken word poetry and hip hop. I brought DJ and his classmates to a reading at Brown University by Staceyann Chin, a Jamaican spoken word poet. DJ later connected with the Rites and Reasons Theater, which is part of the Africana Studies Department at Brown. And when our class went on a college visit to New York City, we naturally had to make a late-night stop for an open mic at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe—the mecca for spoken word. By the time of graduation, DJ was writing phenomenal poetry and rhymes and learning self-acceptance.

Students are constantly giving their teachers feedback; we simply need to tune our radars to their wise counsel.

The design of the Met nurtured intimate relationships. Small cohorts of advisees (not students) stayed together with one advisor for four years; they were liberated from grades, receiving narrative feedback instead; and they called adults by first name, abandoning the hierarchy and formality of “Mr.,” “Ms.,” or “Mx.” Discarding traditional roles and structures was also profoundly confusing—we had to create our own boundaries and rules of propriety. After four years of spending most of our waking, weekday hours together, we were less like academic peers with a teacher and more like a family—audience and actors in a drama full of intimate, emotional conflict and connection. In a typical school, the rituals of senior year—class trips, prom, and graduation—are powerful markers of one of life’s chapters coming to a close; at the Met, all that feeling was amplified by the fact that we were all the main characters in each other’s stories. In a journal gifted to me, many advisees wrote about me as a “father figure” or like a “dad”; perhaps only I saw irony in the fact that I was just ten years older and still figuring out so much.

And about that journal. There was a tradition at the Met where seniors would publicly appreciate their advisor. Students and families gathered, heartfelt words were expressed, and advisors would receive a gift. I didn’t have any expectations until another class of seniors bought their advisor… a shiny new bike. My students gave me... a cheap journal. I opened it and noticed that only some of my advisees had filled it out. I felt let down and wondered what this incomplete gift said about my efforts at teaching responsibility.

Nearly 20 years later, that journal offers a priceless look into the past—like a polished gem refracting waves of light. I gazed into it for a glimpse of my former relationship with DJ. In elegant cursive, he had written:

... what I value the most about our friendship is the conversations we’ve had. I will never forget jus’ chillin’ wit’ you in front of my crib talkin’.... My friend, if there is anything you need to speak to me about, I will be here for you, I promise.

PS: Catch me before you leave as we can have a conversation as friends evenly, not just advisor to student.

Your friend forever,

Domingo

I called DJ occasionally while he was in college. Most of what we talked about is lost in the recesses of my mind, but there is one thing—a question tinged with sadness. He asked, “Why didn’t you push me harder?” Each of those seven words, coming from DJ, dropped like a brick, smashing the rose-tinted glasses through which I had viewed my four years as his teacher; my carefully constructed identity as a great teacher lay in shards. I don’t recall anything else we said to each other on that call. I do remember feeling overwhelming guilt that I had failed to prepare him for the challenges of college followed by a playlist of excuses and defenses: I was young; when I did push, DJ often resisted; what else could I have done? When I took a sober look in the mirror, his words stared back unrelentingly. Why hadn’t I pushed him harder?

That conversation with DJ was one of those moments in my life—like learning about Chinese railroad workers, becoming a father, and learning to speak Korean so I could hear my mom tell stories and jokes in her native tongue—that I look back on and see that who I was before and after was different. It didn’t happen overnight, but over time, his question burrowed deeper into my consciousness and shaped whom I would grow into as a teacher.

I cared deeply and my students felt that.... I challenged myself to learn more about how to teach students in addition to building relationships with them.

The more nuanced response to his question was that while I did push him, I lacked the wisdom of discretion—knowing when and how to offer the right challenge at the right moment. I cared deeply and my students felt that. But for all my formal education, I didn’t know how to teach. I thought that if I simply put in long hours, my students would benefit. I was learning the hard way that I needed to hone my instructional skills and develop a disposition for professional inquiry. When I later started teaching at MetWest, I challenged myself to learn more about how to teach students in addition to building relationships with them. As I learned more about how to teach, I was able to push students to think, read, and write in the ways that DJ was prodding me to do.

DJ’s question was like an asteroid crashing into the surface of my consciousness, leaving a visible and profound impact. But, it shouldn’t take an asteroid strike to awaken us to what our students have to teach us. Students are constantly giving their teachers feedback; we simply need to tune our radars to their wise counsel. We need to find ways to bring students’ voices into the soundscape of our professional learning.

Join the Author’s Visit with the National Writing Project on December 6, 2022, 4:00-5:00 p.m. PST. This webinar is free but registration with “Write Now Teacher Studio” is required. Register here.

Reprinted by permission of the Publisher. From Young Whan Choi, Sparks Into Fire: Revitalizing Teacher Practice Through Collective Learning, New York: Teachers College Press. Copyright © 2022 by Teachers College, Columbia University. All rights reserved.

Photo at top courtesy of the author.