Enabling Change

OK. So We Are Listening to Student Voices... Now What? Inclusive Strategy for Educational Transformation

Topics

Next generation learning is all about everyone in the system—from students through teachers to policymakers—taking charge of their own learning, development, and work. That doesn’t happen by forcing change through mandates and compliance. It happens by creating the environment and the equity of opportunity for everyone in the system to do their best possible work.

With an inclusive, emergent strategy, educators can move from listening to student voices to taking action on their ideas and recommendations in order to transform the learning experience.

“In a sense, this is an ecological project. We have over-farmed the land and undernourished our students and educators while failing to water the roots of a healthy system: student voice, multiple ways of knowing and learning, and community cultural wealth…”

–Shane Safir & Jamila Dugan, p.12, Street Data

A while back a superintendent I’ve been working with for several years and I were talking about student voice. He leaves his office once a week to visit a school for the day, to shadow students and sit and talk with a group of them after school. When he first started doing this, the students were very clear: “Why should we talk with you about our school experiences? You’re not going to do anything about what we say.” He realized they were right; he set out to change that. His district has now been working with Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan, co-authors of Street Data: A Next Generation Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation, on strategies for increasing student voice as “data” for decision-making in the district. Their results are promising.

In Kentucky, the State Department of Education along with the Center for Innovation in Education started a process a couple of years ago called United We Learn, to bring student, family, and community voices into the process of building a new accountability system from the ground up. There, and in similar work in Burlington, Vermont, they realized, they are practicing the “habits” of a new system: the habits of radical inclusion of voices traditionally left out of the conversation about the purposes, practices, and policies of public education; empathy, in listening to and taking seriously what these voices are saying; co-analysis of this new kind of “data” and co-design of initiatives responding to this input; and reciprocity, the continued dialogue with those included in the process about what everyone thinks is happening with it all as a result.

Many years ago, I worked for five years as an outside facilitator for inquiry groups in Santa Monica in a districtwide equity-focused initiative funded by the Annenberg Foundation. Every school and the district office had groups that used an inquiry approach to understanding participants’ personal experiences with equity challenges in the district. Five of the groups I facilitated were at Santa Monica High School (SaMoHi). The district wanted these groups to be voluntary and self-managed. Because of that, each was configured slightly differently. Some were just teachers, while others included counselors, administrators, support staff, and non-teaching staff members. Several early on realized that they wanted to hear from students about their experiences with inequity in the high school. Initially they thought that could be accomplished by holding focus groups or individual interviews with students. But the students who came said, “This is silly. If you really want our opinions and experiences, you should invite us to participate in the inquiry groups, not just be token contributors.” That idea was too radical for most of the teams, but a couple decided to include students as regular members. In the long run, those teams were able to explore the equity challenges at SaMoHi most deeply, and with the most powerful results.

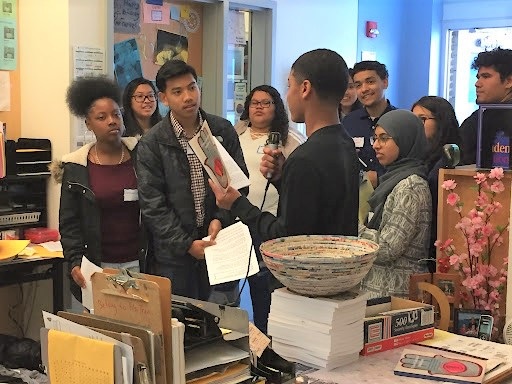

Credit: John Watkins

So, Shouldn’t We Figure Out How to Make the Best Use of That Input?

Still, it is quite a stretch for most schools and school districts to go from thinking of students as (mostly passive) recipients of academic content, with some tip of the hat to addressing issues of social-emotional learning, belonging, and engagement, to the radical inclusion of students as active participants in the critique of their own learning and the redesign of the systems, from the classroom to the school board, that structure that learning.

At the same time, it is becoming more and more part of the national conversation to talk about student voice. If you are somewhere along this journey, maybe you’ve started to try to figure out ways to engage student voice, maybe you’ve started with more traditional student experience or satisfaction surveys, maybe moved on to focus groups, or empathy interviews, or kiva panels. Maybe, if you’re a teacher, you do something like what Chris Emdin does, and have a little rotating group, or “cypher,” of students you meet with at the end of each week to hear from them how they think things are going in your classroom. But the question the superintendent I was talking with heard from his students might remain: “So, now you seem to be listening to us, but what are you going to do about it? Now what?”

In a sense, this is a question to ask about any kind of “data” we have about the work we do. How are we going to use evidence, including input from experience, to inform our practice, strategy, change, and leadership of the work? But a prior set of questions might also be: How are we going to help students feel safe and develop the confidence and skills to participate in this process of having a voice? And how are we going to prepare ourselves to accept that they have something important for us to hear, and to prepare ourselves to work with them in the kind of co-design and reciprocity that the Kentucky folks found themselves involved in? And then how will these two kinds of preparation help young people and adults feel like what young people say matters? In Santa Monica, once the teams included students, it took quite a while for students to feel safe enough to speak up, and maybe even longer for the adults not to be defensive about what the students said, or feel their job was to explain “the way things were” to students; that is, to accept that the students could be equal participants with important questions to raise and insights to share.

In Oakland, where I live and my wife teaches high school English, students are members of their high schools’ Instructional Leadership Teams, and non-voting members of the School Board. Californians for Justice (CFJ) helps develop these young people’s capacity and skill to participate effectively in the policy decision-making bodies. CFJ also helps adults learn how to understand what authentic engagement looks like, so they do not tokenize young people entering these roles. And in many Oakland classrooms, teachers help young people to develop the critical thinking, reasoning, and communications skills, articulateness of voice, and confidence to be active agents of change in their communities, with sometimes dramatic results. As they develop this capacity, their ability to reflect on and contribute to the critique and redesign of their own educational experiences increases. Shouldn’t we figure out how to make the best use of that input?

Credit: John Watkins

The Space and Conditions for Listening to Students

So that’s a start at creating the space and conditions for listening to students. Shane, in a recent blog post, reminds us that there are a few simple rules for what she calls “a pedagogy of voice:”

- Talk less, smile more

- Questions over answers

- Ritualize reflection and revision

- Make learning public

- Circle up

- Feedback over grades

The goal is to “tell the current state story” (Safir, p. 110, Listening Leader), an essential aspect for any strategy development being that it is grounded in acknowledging the way things are from a variety of perspectives. In The Listening Leader, Shane describes two kinds of listening, deep listening and strategic listening. Her choice of words is significant here. Deep listening involves demonstrating empathy and creates the connections between adults and young people that help us shift up the continuum of engagement from “inform, consult, or involve,” toward the “collaborate” or “lead together” end. Strategic listening is where we want to head if we want to answer the question the students posed to the superintendent whose story I described at the beginning of this piece.

Shane explores two aspects of deep listening in her book, deep listening stances and some ways to listen. Deep listening stances include attention to nonverbal cues, mature empathy, and affirmation. Contributing author Matt Alexander then suggests in Chapter 8 that authentic listening to students requires seven actions:

- Listen to students as intellectuals first

- Listen deeply but don't enable

- Walk in their shoes

- Tell their stories

- Ask them how you're doing

- Give them a voice in the classroom

- Organize the classroom around their ideas

Beyond deep listening and listening stances, Shane and Jamila list a variety of other kinds of “street data” that we can collect and analyze as we move from listening to strategy. Some examples are audio feedback interviews (on particular aspects of their experience), listening campaigns, equity participation tracking, ethnographies, fishbowls, home visits, shadowing a student, equity-focused classroom scans, and others. Much of this kind of data involves collecting narratives and the co-analysis with students and families of those narratives to uncover patterns in how our systems are operating. And many more traditional forms of data, that Shane refers to as “map data and satellite data,” can be useful in the context of street data. Often street data, as is the case with audio feedback interviews, can help us make sense out of the “why” behind these more traditional data sets: why is it the case that [x] shows up in the traditional data? That requires co-analysis with young people of the map and satellite data.

What might be the leader’s role in this listening? Here, by “leader,” I mean anyone who is helping lead the process, which could be a positional leader, such as a principal or district leader, or a student leader, or a teacher leader, or a family or community member; when we open up our systems to authentic engagement with student voice, leadership becomes of necessity more and more distributed. Thus, in Shane’s steps to strategic listening, she refers to the essential need to distribute leadership and build capacity. Etienne and Beverly Wenger-Trayner, in Learning to Make a Difference: Value Creation in Social Learning Spaces, describe the leader’s role as curating evidence. One way leaders do this is by having a “value-detecting mindset,” by continually listening both deeply and strategically, by looking for the micro-narratives that describe the experience of students, the experience of teachers, and the experience of family and community members.

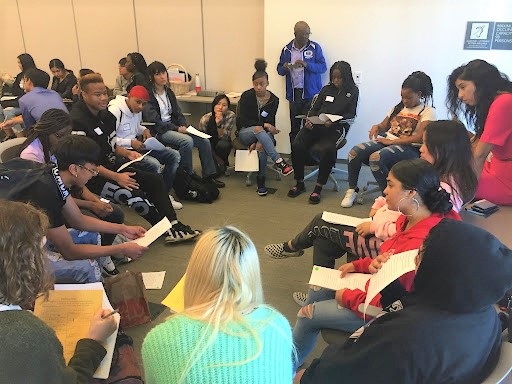

Credit: John Watkins

Shifting from Listening to Strategy

So now let’s explore how we can make the shift from listening to strategy. I want to emphasize that the kind of strategy I am talking about here is not your traditional strategic plan, where a small group of people sit in a room and develop a technical document that lays out everything you intend to do in the next five years with goals and outcomes and benchmarks and such. As Margaret Wheatley states:

“To create better health in a living system, connect it to more of itself. When a system is failing, or performing poorly, the solution will be discovered within the system if more and better connections are created. A failing system needs to start talking to itself, especially to those it didn't know were even part of itself.”

There is a realm of work in every school or district that is purely technical problem-solving, and a set of simple systems can usually suffice to address that realm. However, most of what you are going to encounter as you shift toward greater participation of young people and their communities in strategy, and actually most of the kinds of things you want to change—whether it’s equity challenges or creating powerful and engaging learning settings for students, or better professional learning experiences, hence professional culture, for teachers—will involve collaboration and sharing power with those young people and communities. That is going to require working in a much more dynamic and complex space. These are not discrete, technical problems to solve; these are complex system patterns to shift (Chris Corrigan). And greater collaboration, while it gets you better analysis and better creative input into the what and how of change, requires the skills of facilitating engagement and the negotiation of an often contended space. These complex system patterns require a different kind of leadership competency; these require a different kind of leadership system.

If it’s not simply a technical process, and it’s a much more complex and collaborative process, then it is going to involve how different people construct their understanding together of what the situation is and how to shift it to a better situation. A constructivist approach to strategy assumes that some parts of the work will be complicated but knowable: we need the expertise of a variety of folks, including the expertise of students and families as well as the expertise of teachers, coaches, and content specialists, even when they disagree with each other, to design our work. However, some parts of the work will be very complex, and mostly unknowable, before we dive in and start to see patterns emerging. Richard Elmore described this approach to strategy thusly:

“Strategy is a way of sorting out the incoming complexity and choosing what to make primary focus. Strategy is the set of actions [organizing ideas to help us decide which are the most important problems to be working on] we pursue in order to learn about the environment we are trying to transform, and to use that learning in the service of transformation.”

Let’s take apart what Richard Elmore is describing.

“Sorting out the incoming complexity and choosing what to make primary focus”

Shane refers to this action as “name an equity/deeper learning imperative.” When I was working as co-director of the Deeper Learning Dozen, we developed some thinking about the phases of strategy for transformation. The first two phases, which we frame as “aspirational” (shout out to Andy Calkins of NGLC for this idea), were develop a galvanizing common purpose and develop convictions about what you think is really important for young people. Often a district or school leadership team will sit and think about their vision of success in isolation, or with the board. If we are reorienting our strategy development to include student voices, then students should be part of the process by which these guiding statements are created. Wenger-Trayner describe leading in this process as about appreciating and drawing out narratives about context, seeing patterns and themes in the micro-narratives we’ve curated in context. So this is a process of co-analysis and eventually co-design, which requires what the people in Kentucky were doing: radical inclusion and empathy.

“Organizing ideas to help us decide which are the most important problems to be working on”

When we are working in a complex space, these may seem like very large challenges to address (both the content of this aspect of strategy, and the process of doing it in a much more inclusive way). But let’s look at Elmore’s second thought: a set of actions/ organizing ideas that help us decide which are the most important problems to be working on… that we pursue in order to learn about the environment we are trying to transform. That is, we take some action, in doing that, we learn about the environment, and that helps clarify what we should be focusing on. It’s fractal, in the sense that the little actions we take should be helping us see how the larger system operates, and it’s iterative, so we learn what we need to focus on as we try things out and learn from those trials.

This is strategy as constructivist, social learning. Shane refers to these steps in strategy as identify a few simple rules (constraints) and create a “skinny plan.” The advice that most educational strategists who approach change this way give is to take small steps, try some safe-to-fail experiments. Probe your environment, sense what’s happening, and respond. And do it again and again. This helps develop responses that align with your vision when the complexity makes so much mostly unknowable before you start trying. For more on this approach, check out the Cynefin Framework on responses to complex challenges and Zaid Hassan on strategic direction and space to iterate. The Cynefin Framework is a heuristic we use to help leaders think about what is simple, what is complicated, what is complex, and what is chaotic, so as to lead with the appropriate response to these domains of experience. And Zaid Hassan says it this way:

“A good strategy in the context of complexity would include an iterative process. The simplest form of an iterative process is trial, error, observation, and reflection. Complex social challenges are too complicated for grand strategies. Instead, what is required from [leaders at all levels] is strategic direction and the creation of space. Within that space unfold multiple actions aligned in a strategic direction.”

This is what Elmore is talking about.

Credit: Abbotsford School District

Accelerating Emergence

In the Deeper Learning Dozen (DLD), we described the orienting frame for this phase of the work as “emergent.” You may think the next thing to do strategically is to start building new systems, whether those are at the classroom level (curriculum and pedagogy, assessment), the school level (professional development plans, bell schedules, departments or grade level teams, and various other ways to organize school), or the district level (policies, mandates, supervision and organization charts, work and process flows, budgets). It turns out this approach does not often work very well because it ignores the human nature and relationships of the systems you are trying to change. Working in an emergent way, on the other hand, challenges leaders to disrupt the existing system through recognizing and encouraging the emergence of your people’s new ideas and ways of working, and cultivating and connecting a variety of change agents across the system who are doing that work, including students. How can you do that? Leaders can do that by catalyzing connections as the means to achieving large-scale change (Wheatley and Frieze): notice, then name what is emerging, connect the innovative pioneers, nourish innovative work, illuminate that work for others to see. Chris Corrigan says that leaders can see patterns and themes (the real deeper substance of how systems work, for better or for worse) emerging through co-analysis (again, with students, families, teachers, community members…), or through the little initial small tries, and then connect people and enable exchanges of ideas that create strategies to catalyze shifts in those patterns. Wenger-Trayner say leaders can develop a robust picture of what’s happening (a contextualized root cause analysis that would enable designs/constraints to catalyze shifts in those patterns) and present results in imaginative ways to make them accessible and actionable (with as well as to all constituents). For the Kentucky team, this involved radical inclusion of stakeholders in the co-analysis of all the evidence and the co-design of and co-action on the responses. Everybody then has a role to play. As Hassan says, “Within that space unfold multiple actions aligned in a strategic direction.”

The Constructed Environment: What Specifically Are We Changing?

This next phase of the work moves from the emergence of disruptive new ideas and innovations to the iterative replication of those new ideas into effective practice, structures, and systems. In the DLD we referred to the resulting practice, structures, and systems as the constructed environment. Really, we are talking about facilitating deepening connections among people while formalizing the lateral spread of their ideas and practices. As I suggested above, it turns out that in most district or school plans, leaders often want to move to the constructed environment, to classrooms or school structures and systems, straight from the aspirational aspects of strategy, before discovering and cultivating the energy and efforts of innovative pioneers or change agents.

But the evidence is clear that strategy that moves in this linear and mechanistic way is more often unsuccessful. It emphasizes the “things” of change over the people who are doing the change work. In part, to address this problem, I advocate here for a change in habits of language: as Michael Fullan said, “Change is an implementation dominant phenomenon.” And, “All change is local.” That requires the motivation and engagement of people over time; it goes back to our description of strategy as a constructivist phenomenon. Thinking in terms of “buy-in” and “ownership” is using consumer metaphors for changes that need much deeper authentic shared understanding and engagement. If we start with truly engaging students, why wouldn’t we want to truly engage the rest of the system in transformation also?

There is a question of scale, scope, complexity, and timeframe involved when we start talking about actual change. Students, rightly so, will push for us to demonstrate that we are taking them seriously by immediately “fixing” the “problems” that they identify. Sometimes there are such problems that can be fixed. We should demonstrate good faith by fixing those. But part of the challenge of working with students (as well as working with our overall strategic process effectively) is to engage in our inclusive co-analysis in ways that help everyone develop a sense of what the scale of change is, how complex it is (and therefore what kind of leadership response is needed), and over what timeframe it is possible to make the changes or implement the initiatives that our co-design process develops. But we do no one any service if we reactively try to fix something that turns out to be a symptom of a deeper and more complex challenge. Most likely, if we don’t make things worse in the short run, there will be unintended negative consequences in the long run. Sorting simple from complicated from complex should be a part of our co-analysis process, and helping students to develop the capacity to do that with us will pay off in the long run.

Curating Evidence (“A Few Clear Metrics”)

In the most general sense, we want to know what is happening and if it is making a difference for young people and adults in our system. To rephrase Shane’s quote I opened with: Are we being successful in this new “ecological project?” Are we nourishing our students and educators? Are we watering the roots of a healthy system? Part of addressing these questions is to ask, as I did above, are we developing a robust picture of what’s happening (a contextualized root cause analysis that would enable designs/constraints to catalyze shifts in those patterns)? And are we doing it with radical inclusion, empathy, co-analysis, co-design, and reciprocity, with student, family, and community voices, as the folks in Kentucky are doing? Are we looking at the “ground narratives” (Wenger-Trayner’s name for who we are now and how we came to be this way), the current state story of our schools, district, and communities? Are we looking at the “aspirational narratives,” “the differences participants care to make, [the future story,] the kinds of questions they may have for each other?” (Wenger-Trayner, Learning to Make a DIfference, p.158).

And while outcome measures are important, and even achievement test scores may have some utility, Elmore reminds us that these measures lag considerably behind measures of the improvement in the quality of practice and experience in the “instructional core,” the relationship between teachers (and we can expand “teachers” to include other adults who support student learning) and students in the presence of meaningful content. So, are we looking for the value that is being created in the development of more welcoming, more engaging, more meaningful, and more equitable learning spaces along the way to the longer term outcomes we want to see? And, are we presenting results in imaginative ways to make them accessible and actionable (with as well as to all constituents)? Both to show what we are accomplishing, and to show where we need to reflect and retool, iterate toward improved practice, systems, and policies, along our journey?

Because students are the most influenced most immediately by that quality of practice and experience, and are those most to benefit or not from that, the evidence that would count the most as “a few clear metrics” would be the co-analysis with them of their narrative accounts of that experience. Thus, the other kinds of evidence that Shane and Jamila describe in Street Data would help to flesh out that “robust picture of what’s happening.”

Credit: John Watkins

Students’ narrative accounts of their experience might include examples that are not just those gathered during school-wide or district-wide special occasions, regular kiva panels or focus groups, or even co-analysis of data gathered in student experience and satisfaction surveys. Students’ narrative accounts might already be being created within classrooms, in unit and lesson design, and in formative and summative assessments that are authentic performances or products, demonstrations of their learning, embedded in emergent new pedagogies.

Just last week, my wife, the English teacher in the Public Health Academy at Oakland High School, came home excited, delighted, and overjoyed. Two of her students had been accepted into the University of Southern California. That’s a huge achievement, with 8,198 accepted out of 69,000 applicants, or 12.5% (2022 statistics). She had written recommendation letters for them that drew on concrete examples of the work they had done, not their grades or test scores. Stored in her Google Classroom drive were two years’ worth of writing samples from regular portfolio contributions, written pieces used as notes for them to make claims, evidence, and reasoning for debates about public health and cross-cultural health issues, personal linguistic autobiographies the students had presented to graduate students in education at UC Berkeley, chapters they had written for a book about cross-cultural medicine, podcasts they had created about belonging and othering (related to social determinants of health), designs and agendas they had created for student-facilitated “lit Wednesdays” and regular restorative justice circles, reflections on their learning in relation to class-created learning goals, and much more. There was a treasure trove of evidence of learning, powerful statements in the students' own voices, demonstrating two years of growth, in very concrete ways. Curating the evidence and developing a robust picture of what’s happening for these students takes time, but it enables the crafting of an immensely more compelling narrative than if all she had had were grades and test scores. And these students’ lovely “outcomes” could not have been anticipated in an overall “strategic plan” for her curriculum.

We know what these street data can do. We know how involving students in gathering and curating these narratives and perspectives and analysis, and bringing them into the discourse for planning overall classroom, school, and district strategy, can make a huge difference in what we focus our resources on and what we are able to achieve. So the next time you are trying to listen to students and lift up student voice, and they, with a quite reasonable response, ask you why they should speak up, and what you are going to do about what they say, think about these approaches to the “what next” question. Develop strategy that is radically inclusive, empathetic, involves students in co-analysis and co-design, and creates systems of reciprocity that continue their involvement. Prioritize their involvement, not just in listening to them, but as change agents in strategy creation, emergent new practice, changes in policies and systems, and the iteration, learning, and improvement of all that over time. Get them involved in making happen what they want their school life, learning, and experience to be.

Photo at top courtesy of John Watkins.