What Can a Long Walk in Scotland Teach Us about Education? Joy?

Topics

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

The rhythms of long walks create space for the mind to roam. What kind of experiences do we all need, to be reminded of the awe, wonder, delight, and joy that are essential aspects of being human?

Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist of creating out of void, but out of chaos.

–Mary Shelley, introduction to 1831 edition of Frankenstein

One of the most delightful things about long walks is what happens in the mind as one walks. Initially, one might be concerned with the strength it takes to hoist a pack on one’s back and walk up through glens and bogs and over rocky ridges, or the sore feet that develop from ill-fitting boots or long days on the trail. But soon enough these problems fade away as the body strengthens and careful care of the feet helps heal the pains. The rhythms of long days of walking ease the mind into a delightful shuttle between the necessities of route finding and careful foot placement in crossing bogs, and the expansive capacity of the mind to roam imaginatively among all the possibilities it can explore as the body explores the terrain.

This essay, then, is my attempt to capture some of that intriguing liminal space between my experience of walking through a spectacular Scottish landscape and the roaming of my mind in the process. Years ago, instructing for Outward Bound, I started to call these sorts of parallel roamings “experiential metaphors.” I’ve not found a better term since. So this is my experiential metaphor to share with you now, that came to me as my wife, Jessica (who teaches at Oakland High School in the Public Health Academy), and I walked the Cape Wrath Trail for 22 days and 230 miles in June of 2019.

Toast! …and Cheese and Chutney Sandwiches on White Bread!

A few winters back, before COVID and our Cape Wrath Trail adventure, my son and his family visited for a week. One morning his younger child, Amelia, then about a year and a half, was toddling across the living room floor when her mom called out to her from the kitchen, “Amelia, would you like some toast?” Immediately, and with great enthusiasm, Amelia’s whole body reacted: her arms shot up into the air, she jumped up, and she exclaimed, “TOAST!!!” as if it were the most extraordinarily wondrous thing that had ever happened in the entire universe. We all laughed, reflecting on this lovely degree of awe, wonder, delight, and just pure joy that young children all seem to have as they explore the world.

*** *** ***

It’s now day six of our Scottish walk. We left Kinloch Hourne Farm in the rain, as we had arrived the day before, though slightly drier because of the undemonstrative but attentive caring of our host and his wonderful, warm drying room. He had packed us lunches to go, something we would normally not have wanted, but it seemed appropriate that day, helping to raise our spirits in the wet weather. That morning at breakfast, another guest had told us with some dry humor that Scotland has five seasons… every day. The weather report the evening before had been for clearing. The weather report in the morning had been for showers consolidating to steady rain. The weather report for the following day was for clearing. Often, we discovered, “clearing” meant a small patch of blue sky at eleven in the morning followed by more rain.

We worked our way around the end of the loch and up through a wooded “stalkers estate” into a low pass. Spread out before us in the rain was a great expanse of moor and glen between distant, hazy, grey-green ridges. We took a wrong turn and then walked uphill awhile across open, trackless moor to regain our correct path. We crossed a slightly swollen river on thoughtfully placed stones (our guidebook often warned, “the river will be difficult to cross in spate”), and contoured on a very rough path around the shoulder of a boggy mountain, up into another, higher glen. Streams rushed down from all directions, joining the main flow, which we crossed on stones to join a newer, but muddier track. It petered out in a bowl at the head of the glen, and we then picked our way up toward the pass (“Bealach Coire Mhalagain”) through rocks, tufts of grasses, mosses, and heathers, and across small streams that had etched their way down through the peat. It was difficult, slow going. We could see the craggy Forcan Ridge rising above to our left, our touch point to guide us into the pass.

Suddenly, from behind us clouds welled up, rising to engulf us, swallowing the Forcan Ridge and our pass. We were in total whiteout. We cinched our hoods tighter as the winds rose and the air grew wetter and colder. I began to worry about hypothermia. I continued up, but Jessica called out, “You’re headed too far toward the ridge; we need to be headed more to the right, toward the little lochan that the guidebook describes!” Our guidebook had said, “In the Bealach there is a small lochan which is handy for orientation. Keep to the north side of the lochan and continue northeast to a line of large stones…” We stumbled up into the pass, but we were totally disoriented in the swirling storm and whiteout. There was no lochan to see, nor line of large stones. We were getting colder and wetter by the second. We felt a sense of urgency to do something quick before we got wetter and colder. But what? Jessica thought she could barely see some stones and a way down toward the next valley, out of the wind. So we started down. But soon we realized it was the wrong way, down toward the wrong valley, and had to climb back up into the pass. OK. We have GPS. We have maps. Now is the time for using the navigational system we know, but very carefully and deliberately. That worked. We found the row of stones (it turned out to be a massive stone fence, built who knows when by people for who knows what purpose, arcing across to the northeast under the Forcan Ridge, providing both guidance, protection, and a sort of path, away from the pass, under the ridge, and out of the storm). We followed it into increasing clarity about where we were, as clouds began to lift, and glimpses of the correct valley, to our left (and the incorrect valley, to our right), came teasingly into view.

Jessica sat on the last stones, looking out over the valley, and I walked back a few yards to relieve myself. I turned, and saw her arms shoot out into the air as she made a kind of ecstatic squeak, and yelled out, “Cheese and chutney sandwiches on white bread!” Just like Amelia had exclaimed about toast. The host at Kinloch Hourne had packed us a traditional British lunch item that reminded Jessica of her many visits to the British Isles as a child. And we were safe.

Jessica sitting at the end of the line of large stones, looking out over the valley, after the clouds began to lift.

What kind of experiences do we all need, to be reminded of the awe, wonder, delight, and joy that are essential aspects of being human? What can elicit the kind of ecstatic gratitude that Amelia and Jessica both experienced? Even if some of that awe and wonder are terrifying, as our experience in the whiteout had just been, and not quite so delightful as toast or cheese and chutney sandwiches, what is it that can awaken this intensity of engagement in the experience of this amazing thing that life in this universe is about?

Tony Mackay, in a recent podcast with Jal Mehta and Rod Allen (Free Range Humans), described this kind of learning as comprising “peak experiences, repeated practice, and real world application.” Jessica believes that peak experiences, as well as being joyful, often involve a little fear. Clearly that was the case in our Forcan Ridge crossing. I see that combination of intensity, curiosity, risk-taking, and joy in friends of mine who are truly scientists: taking in every little detail of something with curiosity and delight, and then the precision of inquiry into what it might be about, even if it involves iterations of failure on the way to success. It’s a kind of “joyful rigor,” or “playful inquiry,” that is happening.

But how often do our young people have that ecstatic wonder slowly but inexorably driven out of them by schooling as we have constructed it?

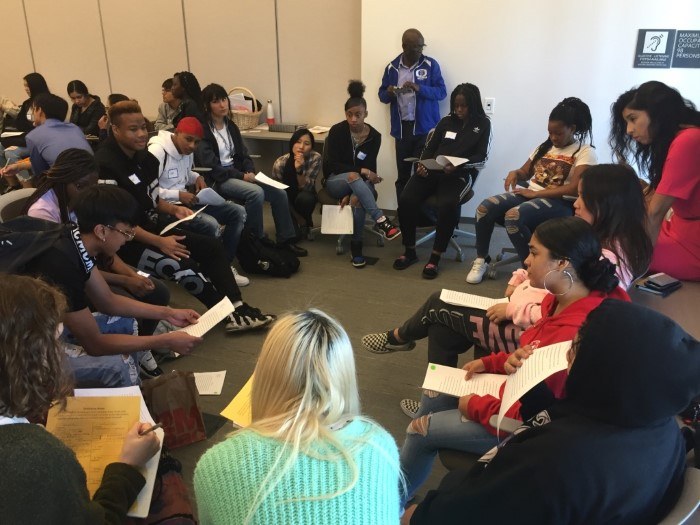

Students in Jessica's course present their linguistic autobiographies for a language, identity, and power unit to graduate students in education at the University of California, Berkeley.

What might we all be about as educators to create and sustain the kinds of learning settings where awe, wonder, delight, gratitude, creative exploration, and the joy of discovery are the norm? Peak experiences? Repeated practice? Meaningful real-world application? What is it we might have to give up that currently produces boredom and disengagement, and slowly kills the joy of learning that young people regularly, and some older people still, are able to conjure up?

Recently I had the great privilege to visit the Mill Bay Nature School in Cowichan, British Columbia, and watch young people whose natural enthusiasm and curiosity were being encouraged by how the school was designed and run. A great expanse of outside space had been given over to what initially appeared to us to be just pure childlike chaos. Some kids were experimenting with building fires and toasting marshmallows. Others were carving with knives. Still others were rolling large plastic cylinders across the field, laughing and tumbling as they rolled over and over inside the cylinders. There were playground elements made of tree trunks. There were bicycles racing around. Some of the youngsters were helping measure boards for a teacher to cut (with power tools) so the kids could build some kind of structure that they had imagined and designed. In the center of the field there was a gathering place, concentric circles of large rocks and tree trunks arranged as seats, and at the center a fire pit and a great platform on wooden wheels that could be hauled with thick ropes over the fire pit to form a sort of stage.

But as we watched with wide eyes while calculating the risks of that seeming chaos, one seven year old admonished us, describing what we were seeing as, “Not chaos! Everybody is doing their playful inquiry projects!” Another child asked if we wanted a tour of the building, which she told us had no classrooms, but spaces for each of their (ungraded) “clans:” Raven, Otter, Sea Hawk, etc. There we found the walls covered with their projects, work tables, materials everywhere, and comfortable couches for them to sit on when they wanted to read quietly or have a small gathering to discuss something (we overheard one conversation as a six or seven year old girl asked her friend, “You seem upset about something. Would you like to talk with me about it?”).

"This classroom sparks joy" was found written on the whiteboard in Jessica's classroom one morning. (Courtesy of Jessica Forbes.)

Our Forcan Ridge experience might have been an extreme example of a joyful (and scary!) “peak experience.” But surely we have the imagination and organizational capacity to create, or support our young people to create, learning spaces where awe, wonder, delight, curiosity, exploration, creativity, and joy abound. Surely we can recover that sense of delight in discovering the existential beauty of toast or cheese and chutney sandwiches on white bread!

Except as noted, all photos courtesy of the author.