Mo'olelo: Building a Culturally Responsive Framework for Assessment

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

This podcast shares the voices of students, educators, and others about a project that grounds assessment in the Hawaiian practice of mo'olelo (storytelling) to build a culturally responsive framework for assessment.

In the two years since we launched the Assessment for Learning Project, one of the most important things I’ve discovered is that assessment for learning is, at a fundamental level, a matter of listening. We believe that good policy is also fundamentally a matter of listening—and so we design our convenings to maximize the time that the educators, school leaders, district officials, and policy-makers are actively listening to one another. Educational equity, too, fundamentally requires listening—especially to those voices that for too long have been silenced or ignored.

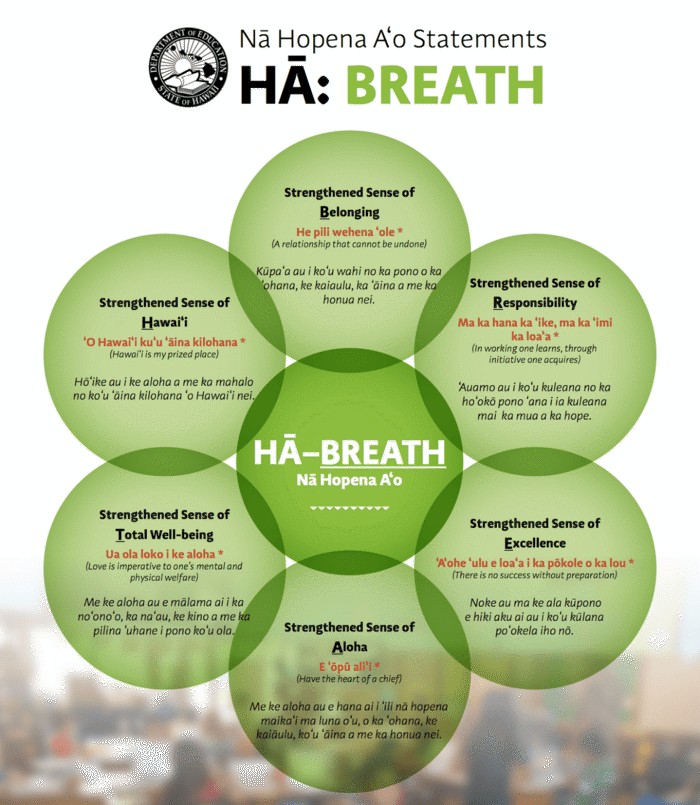

And so we’ve produced a series of podcasts to share the voices of students, educators, and others who are reimagining assessment and experiencing assessment for learning. The first podcast, fittingly, profiles a project that grounds assessment in the Hawaiian practice of mo’olelo (storytelling) to build a culturally responsive framework for assessment. This framework is known as Nā Hopena A‘o, abbreviated to HĀ. In Hawaiian, “hā” means breath or spirit, and BREATH is also the acronym for the six elements of the framework:

I encourage you to pause your reading right now and listen: Voices of Rethinking Assessment: Making Space for All Learners (under Publications).

If you’re still reading, I’ll share a few of the voices you’ll hear on the podcast. “The most important thing that students will get out of this is the ability to see themselves in a path toward success, because it gives them the space to show up from a place of strength.” I’ve heard words like these from youth workers, teachers, principals and families I’ve worked with, but until I met Kau’i Sang, I’d never heard them from a state official. Kau’i, the head of the Office of Hawaiian Education at the Hawaii DOE, helped make HĀ not just an aspiration, but a Board-approved policy of the Hawai’i public schools.

HĀ recognizes that what and how we assess in our school systems sends incredibly strong messages about what (and who) public education values. To create equitable schools and systems, we cannot only assess student outcomes—we must also assess the learning environment and build the collective capacity for all to be a part of the assessment process. As Cheryl Lupenui, another leader of the HĀ work, says, “We know that there are assessments for the learner and the content learned, but the beauty of assessment for learning is that we’re also looking at the context for learning.”

The HĀ statements were developed through a deeply inclusive process grounded in the unique culture of Hawaiʻi, but the framework is only a starting place. In what amounts to a community organizing effort on a statewide scale, the HĀ team has been helping communities hold “HĀ Community Days” that connect to a statewide HĀ Summit. These are days of local service that bring together young people, community leaders, educators, and families to lay the foundation for a shared understanding of BREATH, which become expressions of shared purpose created by a community.

Why service days, rather than focus groups? As Kau’i told me, “Ma ka hana ka ʻike. In doing, one learns.” Shared purpose emerges from shared doing, shared learning. Jessica Worchel, another member of the HĀ team, added, “If HĀ is about strengthening a sense of BREATH, then it is critical to provide experiences where all senses are engaged and pilina, or relationships, are strengthened.”

It’s easy, as I did at first, to see the HĀ work as uniquely applicable to Hawai’i. But listen to the words of Maddie, a student who has been a part of a HĀ pilot site. “Toward the beginning of this class, I didn’t feel as though I belonged, but that I was just here. I felt responsible, but not so much needed. Welcome, but not necessarily wanted.”

I’ve never met Maddie, and I don’t know what made her feel, at first, unwanted in class. But as I sit here 5,000 miles away, her words bring me closer because I often felt feelings very much like those when I was in school. As I write, my town is in the midst of a strategic planning effort, asking what does it mean to be educated? I intend to bring what I’ve learned so far from HĀ into this process, so that our community finds shared purpose to help all of our young people, our educators, our community ask the questions that Jessica asks on the podcast: “What do I belong to? What is my responsibility? What will I excel in?”

And If we really do this in my community, I hope that we’ll measure the success of my kids’ schools not only by their test scores and graduation rates, but also whether our children, our staff, our families say things like Maddie did after her experience of HĀ:

“Through this quarter working with my group on project serenity, my HĀ has exceeded my expectations, almost capping the charts. I’m a needed person in my group and I get things done, but not only am I needed in my group, I feel needed within my class.”