New Designs for School

MyWays #2: Learning Design as Rich as Your Definition of Student Success

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Answering Next Gen Learning's Three Big Questions - Part 2

Editor's Note: Visit myways.nextgenlearning.org for the most up-to-date information and tools for the MyWays project.

Today’s MyWays blog post provides tools for you to use in connection with the second of these three Big Questions facing anyone contemplating a transition toward next gen learning:

- How well are we defining and articulating what success looks like for students attending our school?

- How well does our design for learning and the organization of our school directly supportstudents' attainment of our richer, deeper definition of success?

- How do we gauge students' progress in developing those competencies? And: How can we measure and articulate our school’s overall performance, beyond proficiency in ELA and math?

For tools to answer the first question, see part 1 of the series; a third blog, to be posted later this week, will focus on the last question.

For schools reflecting principles of next generation learning—personalized, student-centered, competency-based, blended, experiential, designed around deeper learning goals—developing and activating strong, clear answers to these questions is an imperative. With the assistance of the primary MyWays researchers and authors, Dave Lash and Dr. Grace Belfiore, NGLC has been incubating a project for the past 18 months intended to help our grantees and all educators entering this space to do exactly that.

Whether you are already engaged in designing or implementing next gen learning, or considering it (in part enabled by the new Every Student Succeeds Act), we hope you will use the MyWays tools as “critical-friend” analytical lenses to examine the depth and clarity of your answers to the three Big Questions of Next Gen Learning. This second blog introduces the research and framework we have produced to help you and your colleagues address the second question.

Exercise 2: Learning Design as Rich as Your Definition of Student Success

Strong consensus on the competency goal-line is the essential first step. (That was Exercise 1.) Now for the hard part: does your learning design and school organizational design actively, directly, and fully support that definition of success?

Try opening this exercise by asking your staff to write down the most valuable and enduring learning experience each of them can recall from their high school years. Then do a lightning-round of their personal stories. This is how Larry Rosenstock, founder of High Tech High, launches workshops for schools and organizations plotting to move toward HTH’s deeply embedded (and off-the-charts successful) model of project-based learning. In more than 200 such sessions, he reports, the vast majority cite learning experiences—either in school or outside of it—that were engaging, experiential, multi-modal, authentic, and that gave them opportunities to shoulder genuine responsibility/ownership and to “go deep” in developing a special expertise. Like the MyWays framework on defining success, High Tech High’s learning model simply reflects what most everyone already knows from personal experience, and what great educators have always sought to generate.

We may know it, at a deeply personal level—but it’s not how most schools operate. Even NGLC’s breakthrough model innovators and grantees tell us that they fight a constant battle to preserve the boldness of their original school design and the degree to which it reflected the richness of their definition of student success.

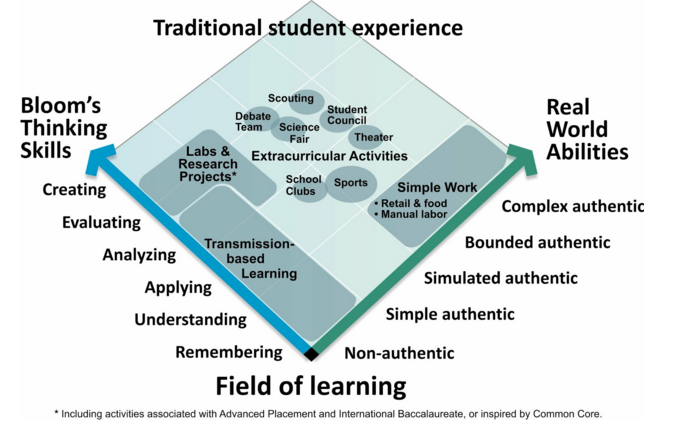

Take a look at the graphic below. Virtually all of us experienced “school” within the confines of the left side of the infield, shown in the traditional school experience mapped on this MyWays field of learning graphic. Transmission-based learning, the central modality in schools over the past century, has focused mainly at the lower end of Bloom’s taxonomy of thinking skills, and primarily in artificial, inauthentic contexts for learning.

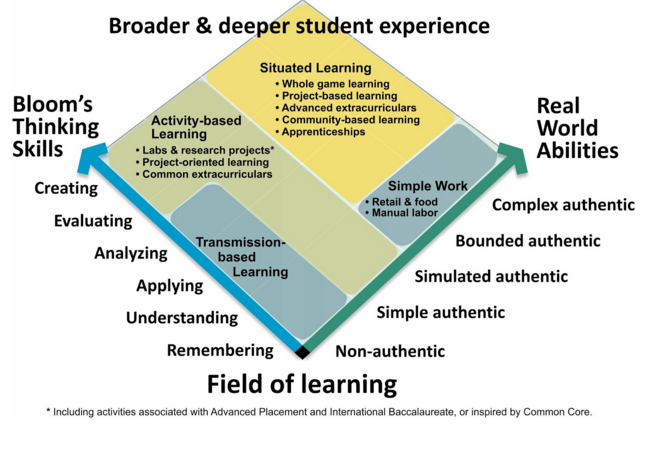

What kind of learning design would enable students to experience learning across the entire ballfield? It might look like the “next gen” ballfield shown below, with a full range of modalities that use situated and active forms of learning to make the experience meaningful, relevant, and engaging for students and, in so doing, locate more of it toward the upper end of Bloom’s taxonomy.

The Basis for the Learning Design Exercises

What characteristics should learning designs incorporate to stimulate a rich set of experiences for students across the entire field of learning? Our suggestions are gathered around what we’ve learned from NGLC’s national grantees, including some that are four years into developing next gen learning models, and around a learning-design framework developed by David Perkins at Harvard University’s Project Zero and published in his book, Making Learning Whole. Perkins’ ideas rebut the natural tendency we all have, once we embrace the full set of 21st-century competencies, to convert them straightaway into separate assessments, curricula, and class schedules. After all, if we’ve learned anything from two decades of standards-based accountability, it’s the real-world truth in the maxim what gets measured gets taught.

In Perkins’ view and ours, it is the assessment-driven molecularization of learning—as a guiding principle of pedagogy—that robs learning of meaning, reduces it to short-term memorization tasks of little value, and leaves students utterly disengaged. The grave risk in the increasing consensus around richer, deeper definitions of success is that we will apply our standard suite of strategies—traditional on-demand assessments, enshrined by accountability—and generate a whole new round of unintended consequences in the form of pedagogy aimed primarily at delivering “proficiency” on those exams. We teach only up to the limits of what we can assess, and only in ways that can be isolated for scoring and comparing.

Learners, though, are no more likely to develop skills in Self-Direction, Perseverance, Positive Mindsets, and Collaboration by studying them as distinct disciplines than they would be to learn how to take great pictures by reading a book. There is some value in the studying, but the muscle-building in these competencies really requires practice and reflection. Quoting from one of the forthcoming MyWays reports:

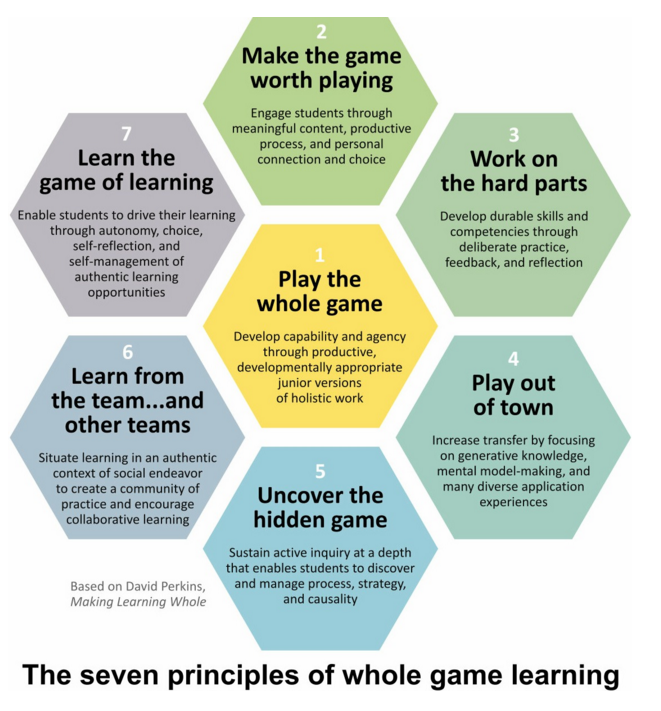

Perkins uses the learning of baseball to underscore that learning anything important takes more than learning the individual elements, or learning “about” the game; instead, learning baseball and other complex skills requires being fully engaged in how all the elements interrelate, how to judge what works and what doesn’t, and how to improve through doing. As Perkins put it, “the natural engaged purposefulness of such occasions is what learning by wholes aims to capture.” Because “whole games” (playing baseball, conducting scientific inquiry, making an animated film, or running a business) are complex, Perkins introduces the concept of a “junior version”—an accessible experience that is scaffolded in developmentally appropriate ways, while still keeping the essence of “the game”—like Little League is to the game of baseball, robotics competitions are to the work of engineers and tech innovators, or running student organizations are to running a business. Junior versions, we believe, can play a major role in the design of learning that can address the breadth and depth of the MyWays competencies. In a growing number of schools across the country, they already are.

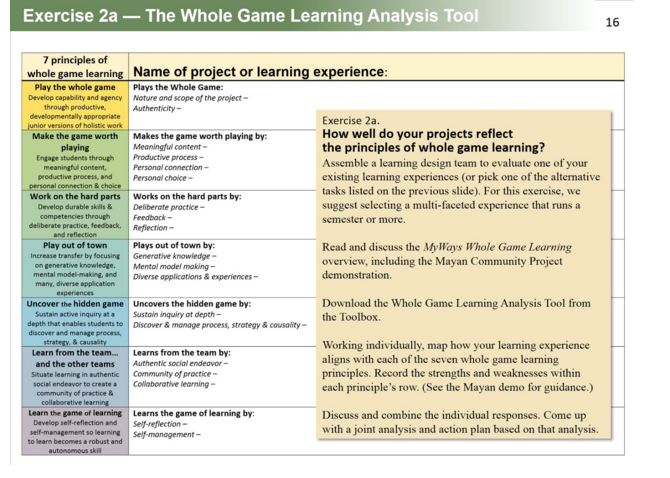

Perkins organizes whole game learning into seven principles, as seen in this MyWays graphic:

This lens is the most complete and intuitive one we’ve found that can help educators distinguish between project-oriented learning and project-based learning. The former employs activity to spur engagement. (Think: dioramas.) It has value but normally does not reflect the rich set of learning dimensions Perkins describes. The richest, most enduring versions of the latter are deliberately designed, whether their developers use Perkins’ language or not, to encompass some or all of his seven features of whole game learning. Perkins’ principles, along with a typically well-constructed lesson plan from High Tech High, lie at the heart of the staff exercises we provide to you here.

The Tools for the Learning Design Exercises

In the MyWays Beta Toolbox, you will find the MyWays Three-Big-Questions Exercise Set. Exercise 2 includes three tools designed for your use in engaging with staff, board, and others around how your school’s learning design directly helps students make progress towards your complete definition of student success—the second Big Question. Those exercises are presented in the slide deck; in addition, there are tools provided as separate docs and a Whole Game Learning overview.

Exercise 2a: How well does your learning design reflect the principles of whole game learning? Use the worksheet shown below, and available in the Toolbox, to have your staff conduct an analysis of one or more of your best curriculum units. In using the seven principles of whole game learning as a friendly critical lens, you should be able to spark a rich, generative discussion. Try it with your staff’s favorite PBL lesson plan and, to extend the discussion further, with one of your best traditional lesson plans. The seven principles are unpacked and described in the Whole Game Learning overview.

Exercise 2b: How well do your projects harness the benefits of “junior versions”? A separate worksheet in the Toolbox enables you and your staff to explore the degree to which, in the PBL experience you chose for Exercise 2a (or another substantial PBL experience) your students are able to engage appropriately with what Perkins calls “junior versions” of real-world activities—meaning, a setting that offers genuine authenticity, relevance, a broad range of challenge, and an appreciation for the whole as a sum of its parts. Calibrating this fit includes both knowing your students well, understanding human development, and continually tuning the learning design. How well do your projects do this? (See the Whole Game Learning overview for more on junior versions.)

Exercise 2c: How well do your projects map to the MyWays competencies? The third tool within this set of Learning Design exercises enables you and your colleagues to plot the competencies your current projects help students develop within the MyWays framework. You may discover that they support the development of more skills than you had imagined, and—as important—your discussion may generate good ideas to extend the project’s value to previously unaddressed skills.

Additional materials in the slide deck and the Whole Game Learning overview provide a portrait, viewed through the MyWays lens, of a typically well-constructed lesson plan from High Tech High. It is a middle school–oriented, interdisciplinary project spurring individual and group research on the Mayan culture and Mayan areas of present-day Guatemala. Among other dimensions, the project supports students’ application of knowledge to collaborative writing and illustration of a children’s alphabet book on the Mayan culture, and consequent publication, marketing, and sales of copies of the book to fund schooling for seven Guatemalan students from impoverished families.

My next blog post, the final one in the series, focuses on the third of the Three Big Questions: How do we gauge students' progress in developing those competencies? And: How can we measure and articulate our school’s overall performance, beyond proficiency in ELA and math?