Next Gen Learning Requires Next Gen Change Management

Topics

Next generation learning is all about everyone in the system—from students through teachers to policymakers—taking charge of their own learning, development, and work. That doesn’t happen by forcing change through mandates and compliance. It happens by creating the environment and the equity of opportunity for everyone in the system to do their best possible work.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Mission Vista High School in Vista, CA, empowers educators to own and lead the transformation of student learning.

Change cannot be put on people. The best way to instill change is to do it with them. Create it with them.

—Lisa Bodell, CEO of futurethink

In the fall of 2018, Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC) was awarded a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York to support research into and development of a next gen approach to change management, one that leads to enduring, fundamental transformations in school design, student learning, and achievement of 21st-century outcomes. In place of top-down, compliance-driven change efforts, next gen change processes are built on the principle that adults, as well as younger learners, do best in environments that enable agency and autonomy, honor purpose and diversity, and provide opportunities to develop mastery.

To explore, unpack, and document what this kind of change looks like in the context of real learning communities, NGLC has engaged with several districts across the U.S. One of these is the Vista Unified school district in Vista, Calif.

For this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning, I spoke to two school leaders at the district's Mission Vista High School, a dual magnet high school that provides specialized programs in arts/communication and science/technology. Nicole Allard, Mission Vista's principal, and Michelle Daum, English department chair and curriculum specialist, described their school's next gen approach to transforming learning, including:

- Exploring personal, as well as shared, reasons for change;

- Setting collective and individual goals aligned to the new vision; and

- Sharing leadership to deepen and sustain change.

Understanding Our "Why?"

Listen to your staff because no one ever starts their day saying, "I want to do exactly as I have always done and I never want to get better." Merge their whys and your whys.

—Nicole Allard

Mission Vista High, founded a decade ago with 200 students, today serves a diverse community of 1,700 learners and has been recognized as a School of Distinction by Magnet Schools of America. Building on a model that was already strong, the school embarked on an initiative in 2017 to move teaching and learning from the traditional to the transformative.

Personalization of learning is occurring throughout the district, but individual schools like Mission Vista are empowered to shape that change and create a pathway to that goal as a community. The high school's staff, for example, selected project-based learning as the engine that would power learning transformation and adopted the definition of personalized learning set forth by Allison Zmuda, Greg Curtis, and Diane Ullman: "a progressively student-driven model of education that empowers students to pursue aspirations, investigate problems, design solutions, chase curiosities, and create performances."

Change is a difficult and even scary process, Nicole observes, so an essential first step in any transformation is figuring out why change is needed. At Mission Vista High, "understanding our why" is both a collaborative activity and an individual one, what Nicole refers to as the "personal why." For the last two years, considerable educator professional learning time has been devoted to sharing and articulating school, department, and individual educators' motivations to change the ways teachers teach and students learn. "We revisit our why all the time," she says. "It's not a one and done event."

For Nicole, her personal why for transforming learning was the result of "being exposed over and over to the changes in our global economy and what employers are asking from kids." Not surprisingly, when she speaks to educators about Mission Vista, she points to a broad range of critical skills and knowledge identified by the World Economic Forum, the San Diego Workforce Partnership, or the NGLC MyWays Student Success Framework.

"We have a responsibility and a duty to prepare kids for the world of work—whether that's at 18 or after college," she explains. "I realized that a traditional high school was not going to meet their needs. Teaching them content alone is not adequately preparing them to be competitive in the global marketplace." As a result, Nicole's personal why for change has been an exploration of "what does preparing for a career look like in a high school?"

According to Michelle, her personal why "clicked around wanting learning to be more personal, relevant, complex, and meaningful." The elements of personalization that excited her included the "push toward student agency, having more choice, and being part of the learning process: setting their own goals, identifying their own audience, and generating more of their own learning based on their interests and passions."

Setting "Wildly Important Goals"

Leave things open for teachers and offer multiple ways to jump in. How can you personalize learning for kids if you don't personalize learning for teachers?

—Nicole Allard

Both Nicole and Michelle describe change at Mission Vista High School as a combination of shared vision and individual educator agency. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the school's approach to goal-setting, what Michelle calls "our WIG work." Each academic year, in a collaborative process, the faculty creates a Wildly Important Goal—or WIG—that drives the professional learning, curriculum development, and classroom instruction. For example, the WIG for 2018-19 calls for all educators to offer students at least one personalized learning experience in each course by the end of the school year.

As Michelle points out, the schoolwide WIG reflects a shared commitment to change: "This is the work we want to do together. We agreed to be part of this as a staff, and it's something we all want to do."

At the same time, she notes that Nicole is committed to "having teachers start where they are" and empowering them to determine how—and how deeply—to engage with the school's WIG. Mission Vista educators use an analogy to swimming to describe the different approaches to the shared goal. "Cannon-ballers," according to Nicole, are the educators who have thrown themselves wholeheartedly into personalization this year, making significant changes throughout their curriculum. Others, whom she refers to as the "toe-dippers," are making more incremental changes, trying out personalization in individual lessons, projects, or instructional units.

All educators, however, are supported to take risks with their teaching to achieve the common goal. Continuing with the swimming analogy, Nicole says, "I tell them that it's OK to belly-flop as long as they get back up. I emphasize that this is all new and I also model failure by saying, 'I tried this, and it bombed' or 'I made a mistake.'" Whether they dip a toe or immerse themselves in personalizing learning this year, she says, "My teachers care about doing great things for kids. If it means risking and changing, they are willing to do that because their personal why is all about kids."

Another key opportunity for teachers to exercise agency is through setting their individual WIGs. At Mission Vista High, Nicole starts off the year by spending 20 or 30 minutes with every member of the faculty to discuss teachers' personal WIGs and ways she can support them—with resources, paid work time outside of school, observing other teachers, or targeted feedback on lessons, for example.

This level of personalization of professional learning requires a significant investment of time. Nicole estimates that she spends 40 hours at the start of each school year meeting with educators, with follow-up opportunities to check in throughout the year. However, she describes this work as "really powerful. You have to talk about the individual. Everyone has their own WIGs aligned to their personal why."

Nicole reports that about 90 percent of teachers' goals this year were directly tied to the schoolwide goal of personalizing learning. Choosing their own WIGs, she says, "supports personal ownership of the transformation. Teachers have the agency to decide 'what does the change mean for me?' For some, it's to transform an entire course, such as rethinking assessment or integrating new habits and skills or project-based lessons throughout the curriculum. For others, it's working on creating authentic, real-world learning or supporting learners to be self-reflective. But all are about moving toward student-centered learning."

Sharing Power to Sustain Change

The schools and districts that are transforming learning tell us that working together on a common goal, like the WIGs at Mission Vista High, is exciting and energizing, but it is not easy. The changes required to create the education students need can also involve confusion, periods of chaos, and setbacks. It therefore requires long-term will among decisionmakers and an ongoing investment in the people in the system. A core practice for sustaining change, then, is to grow ownership and nurture distributed leadership in the change process.

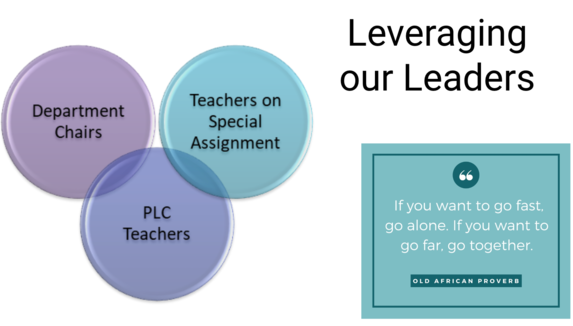

The teacher roles that help lead the change at Mission Vista High. (Courtesy of Mission Vista High School.)

In addition to receiving support for change from district leaders and Nicole, educators at Mission Vista High also learn from and with peers who have taken on leadership roles. The role of department chair, for example, is part of many traditional high school models, but according to Nicole and Michelle, department chairs can also be leaders for change.

Departments at Mission Vista establish their own WIGs, and personalizing learning is an action item on every department meeting agenda. Michelle recalls, for instance, how the department chairs worked together to map out the resources, like training and release time, that teachers would need to meet the school's shared goal, as well as "setting up a plan—or scoreboard—for how we would know we had reached our goals."

To support Mission Vista educators on their personalization journey, Michelle also maintains a folder of resources, reflections, and artifacts of practice for personalizing learning, as well as sample student work. "We share our own lessons," she explains, "and we reflect on the trends we are seeing. How are we personalizing? How are we making learning authentic and relevant, with student choice and voice?"

Leadership for personalizing learning is also provided by two other groups of teacher leaders at Mission Vista High School: Professional Learning Community (PLC) leaders and teachers on special assignment. Among other duties, these educators support change by facilitating seven to 10 professional learning experiences throughout the year. Educators can select the ones that are most relevant to their goals and growth and be taught by colleagues who are engaged in similar work.

Nicole gives credit to the teacher leaders for the faculty's high attendance and deep engagement with professional learning, noting that, "At some schools, people call in sick on professional learning days." At Mission Vista, on the other hand, distributed leadership "models to teachers what we are asking them to model for kids. If you are not giving teachers agency and choice, you are missing the boat."

As a parting thought for fellow principals who might "worry about giving teachers agency," Nicole shares her experience from this year: "I've been blown away by our teachers. Our WIG was to offer one personalized opportunity for students by June. This could have been a single lesson, but 77 percent have already done an entire project or unit or transformed a practice like grading. Give teachers choices and agency, and they will give you so much more than you would ever get if you just told them what to do."

Resources

- The Mission Vista Scoreboard for Personalized Learning, created by the school's teacher leaders, tracks the school's progress toward the Wildly Important Goal for personalizing learning in the 2018-19 school year.

- This MVHS WIG document, used at faculty PLC meetings, describes the process of creating, revising, reflecting, and celebrating progress toward the school's Wildly Important Goals.

- This list of personalized learning strategy sessions, facilitated by 15 faculty members, illustrates both the range of professional learning options educators could choose from and the school's distributed-leadership approach to change.

- A flier, created by MVHS students, communicates the mission, vision, and values that underlie the school's transformation of learning for student success in the 21st century.

- NGLC's Innodoption Project is advancing the field's understanding of what it takes to solve the challenge of enabling change. With support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, NGLC is partnering with several school districts, including Vista Unified, along with experts in K-12 education change management, to identify, synthesize, and disseminate effective change-management strategies.

- In this EducationWeek Learning Deeply blog post, Jal Mehta explores "emergence" as a third way between top-down and bottom-up approaches to education reform—a way of perceiving energy and interest in the system and then connecting people and creating opportunities for sharing and growth.

- Nicole Assisi's article about successful leadership offers 10 principles for moving your school toward a distributed approach to leadership.

Photo at top: Students in Michelle Daum's English class lead a literature circle discussion. (Courtesy of Mission Vista High School.)