Designing for Equity

Nurturing STEM Identity and Belonging: The Role of Equitable Program Implementation in Project Invent

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

STEM curriculum and programs can foster STEM identity, belonging, and future-resilient skills among young innovators passionate about making an impact in their community.

My Journey: From Afterschool Educator to Project Invent Fellow

Not unlike many youth development professionals, I stumbled upon afterschool education by accident. During my undergraduate studies, I was looking for opportunities to meaningfully fill my time (and my resume) outside of coursework and deepen my relationship with the local community in Baltimore, Maryland. One day as I was scrolling through the student job board, I found an enticing position: “STEM Teaching Assistant.” I immediately sent in my application. As an applied math & biophysics student, this sounded fabulous for gaining more experience as I prepared for the post-college job hunt in six months. I didn’t read the description that I would be teaching fifth and sixth graders.

What followed this quick decision was a whirlwind of a semester; it was full of plastic syringe kinetic sculptures, photography field trips to graffiti parks, and precarious learnt-on-the-job classroom management. It was one of those special, fleeting moments that held a life-altering path ahead. At that time, I had no idea it would thrust me into a career of passion, adventure, challenge, and advocacy. During my time at this neighborhood afterschool program in Baltimore, I was a passerby in these students’ lives. They, however, propelled me into a world of education I didn’t know existed—work driven by bridging the gap between youth farthest from opportunity and the technology education that deserves to be accessible by all.

After graduating from college, I found myself itching to continue upward within education. This led me to Denver, Colorado, where I accepted my first full time position as a college and career pathways coordinator for the Best Buy Teen Tech Center at the Gold Crown Foundation. Hungry and energized, I entered a new professional era full of opportunities I could create for young people. I enthusiastically drank from the fire hydrant of new, incoming information about the program, all while learning and adjusting to a new home. I quickly became overwhelmed with my ideas for program improvement, bouncing from spreadsheet to spreadsheet, pouring over archived emails, and tearing apart decades-worth of documents squirreled away in filing cabinets. Then, not even one month into the job, I was approached with an incredibly powerful question: who should be our national partner for the C2C Program? My leadership team was divided between two possible options, and I, the new hire and youngest person on staff, was set to decide the fate of our program. I weighed the two options carefully, digging into each program deeply, setting up meetings with the program managers, and charting out pros and cons. I had finally settled: Project Invent.

It sounded nice, Project Invent. I had a STEM background. I knew how to make things. During undergrad, I worked with a friend to design a community solar workshop where we recycled old solar cells and hooked them up to an Arduino. On another occasion, I worked with graduate students to prototype an Ebola personal protective equipment suit. This was up my alley, and this was something I cared about. This was something I could bring to the program youth. This will get them excited about technology.

Soon after, I connected with the Project Invent team. At that time, it was all the mighty trio of Founder Connie, Program Director Kelly, and Program Manager Jillian. They greeted me with empathy and a calm excitement, which at the time, was so welcomed and needed to ground myself in preparation for the tightly packed year ahead. I found myself enthralled with the possibilities of Project Invent for the year, but bound by a strict schedule while juggling mounds of required career-readiness related curriculum. If you could see me at that time, I was a perfect mimicry of the infamous Charlie Day meme with the overlapping paper, bulletin board, and red string. Only in my case, it was with Project Invent’s signature sticky notes and sharpie scribbles.

Fast forward two incredible program years, and I was departing Gold Crown with contentment, happy tears, and see-you-laters because I never say goodbyes. My first year as a Project Invent fellow, I mentored a team of three young women, first in their families to graduate high school, to a Project Invent award at Demo Day X. We also had the support of our mentor Samantha, an industrial designer who championed the girls’ work and made an immeasurable impact on their confidence, aspirations, and ambition. The team, mentor, and I united over our shared identities, and we built strength in our small but impactful group, together. We worked in tandem to find a community partner for our invention, built a device for students to participate equitably in PE class, and pitched our hearts out. All three young women have pursued higher education, the first in computer science, the second in architecture, and the third in business. They did that. They bridged the gap.

Boost of Mind Invention Team. Left to right: Odalys, Ashley, Brianny.

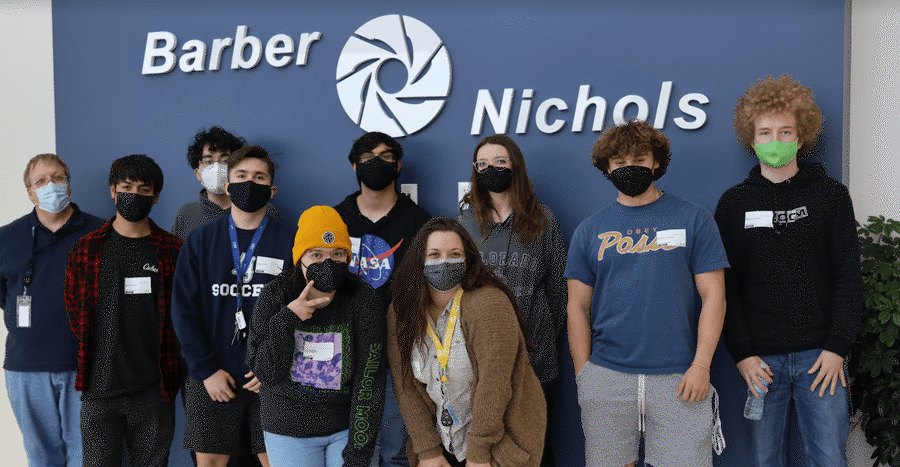

My second program year with Project Invent saw a huge increase in our team size from three young people to nine. This program year, each participant was so diverse from one another. They all came from different schools, different grade levels, different backgrounds, spoke different languages, and had different levels of experience in computer programming. Half of the team had never had any technical experience before Project Invent. Still, they all brought curiosity and enthusiasm to the project. They persevered through long nights of programming and prototyping their ambitious ideas. They made heart-felt connections with our community partner and empathized profoundly with the children’s hospital pediatric patients. It all came together in the end with their remote learning therapy invention designed to help learning therapists engage patients while conducting sessions. While they didn’t catch an award that year, they all continued onward with great success, pursuing a range of STEM careers: mechanical engineering, aerospace engineering, a machining apprenticeship, pre-veterinary medicine, and an electrician journeyman apprenticeship. They bridged the opportunity gap, too.

Readify Invention Team. Left to right: James, Chris, Angel, Mentor Val, Elijah, Facilitator Alexis, Kaiya, Marcus, and Robert.

At Project Invent, our mission is to empower all learners with future-resilient mindsets and skills to succeed individually and change the world, through invention, so they too can help young people bridge the STEM opportunity gap. Now in my role as a program manager with Project Invent, I practice being an attentive professional development provider, a mindful program coach, and an intentional support system for all educators as they take their youth inventors through our flagship program. As I write this reflection, I’m excited to be looking ahead at my two year anniversary as a member of the Project Invent team—although I have been invested in the Project Invent mission for much, much longer. I have firsthand seen the transformation that this program has on young people by being the throughline that connects their interests, talents, and skills to the real world through creative problem solving.

The opportunity gap is especially important in the context of STEM. Without a mindful approach to introducing STEM, we may alienate or marginalize students even more.

The Opportunity Gap in STEM

Conceptualizing STEM access as a gap across student identities and backgrounds is helpful in visualizing equity. At Project Invent, we often focus on the opportunity gap in education, which characterizes the lack of equitable opportunities for youth in a framework that addresses institutional and systemic racism. Compared with deficit thinking, the framework of the opportunity gap “shifts [focus] from assigning responsibility for the gap from the individual to society” (Shukla et al. 2022).

The opportunity gap is especially important in the context of STEM. As educators, we may want to dive head first into bridging this gap by providing technology and STEM access to students in our classrooms immediately. However, without a mindful approach to introducing STEM, we may alienate or marginalize students even more. While working as a Project Invent fellow, I built a project onboarding period into our course plan. During this time, my team and I built relationships with one another that solidified a feeling of safety and prioritized belonging. We played team building games, youth reflected and explored their personal and professional interests, and we cultivated a joyful learning environment together. This year, I’ve worked with fellows who cite that Project Invent is the first time students have had to build something and present their ideas to a group. Without a mindful approach to their former experiences and current starting point, students could be left feeling intimidated and shut out of STEM before they even begin this journey.

One way to mindfully introduce STEM concepts and projects to students who have been impacted by the opportunity gap is to explore the idea of STEM identity. STEM identity can be defined as “the concept of fitting in within STEM fields, specifically, the way individuals make ‘meaning of science experiences and how society structures possible meanings’” (Carlone and Johnson 2007, Hughes et al. 2013). STEM identity in students is so important because it takes an influential position in one's success in education and career trajectories (Singer et. al. 2020). How do we ensure that students experience a sense of self tied to STEM, and their participation in it? We can use belonging as an entry point, and build on their experiences and personal growth from there.

STEM identity is inextricably tied to the feeling of belonging. When students feel a sense of belonging in our spaces, our programs, and our curriculums, they are set up for success to learn, grow, and fail productively. When we construct feelings of belonging for our students, they can use belonging as a foundation for their ambition, resilience, and creative confidence to pursue STEM long-term. For me, I see belonging as going beyond inclusion. We can set up our parameters to ensure all students are included in the invention process, and then we must put in intentional work to ensure they feel like they belong.

In practice as an educator, inclusion might look like having every student build a cardboard prototype independently before building a prototype as a group. This also looks like baking in accommodations to your program for students with disabilities. This encompasses differentiation, task or material adaptations, notetaking, recording lectures/conversations, ELL support, and so much more. To bring educator practice from inclusion to belonging, this could look like taking the time to build a relationship with each student, understand their background, and work with them individually to align their interests with the invention process. It can also look like lots of team building activities, reflection time, and meeting students at their level—whatever that means for them.

Equity Strategies for STEM Identity and Belonging

When I look across educational journals, I can see that K-12 researchers are very interested in learning more about STEM identity, belonging, and increasing diversity in STEM fields. While every publication is investigating a different question, one prevalent theme is the importance of diversifying learning environments. We need more diverse representation not only among educators, but also leadership teams, mentors, and other professionals that support our classrooms. In addition, a culturally responsive curriculum that showcases diverse voices, perspectives, and images where youth can see themselves is also imperative in cultivating belonging.

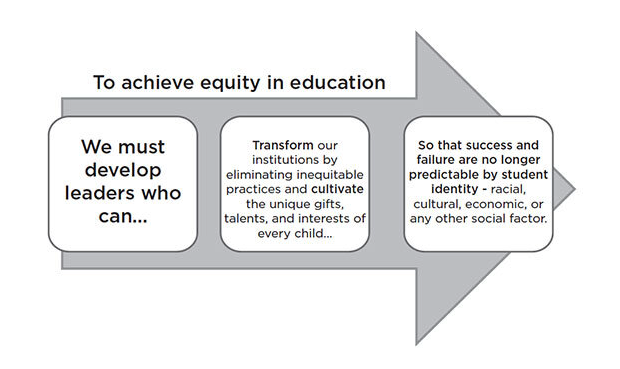

Belonging is also rooted within equity. In order for a young person to truly connect with others, they should feel that their unique gifts, talents, and interests are celebrated within our spaces. Belonging benefits when we transform our classrooms by eliminating, as much as possible, inequitable practices.

National Equity Project’s development pipeline to achieve equity in education.

The National Equity Project (NEP) defines educational equity as every child receiving what they need to develop to their full academic and social potential. NEP also provides a development pipeline to achieve equity in education (see the figure) and shares that “working towards equity in schools involves: Ensuring equally high outcomes for all participants in our educational system; Removing the predictability of success or failures that currently correlates with any social or cultural factor; Interrupting inequitable practices, examining biases, and creating inclusive multicultural school environments for adults and children; and Discovering and cultivating the unique gifts, talents and interests that every human possesses.”

In one article focusing on Black students’ experience with STEM, Liane Hypolite highlights three strategies to one day remove STEM opportunity gaps: “(1) culturally responsive, relevant, and sustaining pedagogies, (2) problem- and project-based, participatory curricula, and (3) a commitment to civic action and civic engagement.” These three points illuminate the significance of a coupled design and implementation strategy when addressing this issue. Not only do we want to focus on cultivating belonging within our programs, but we also can thoughtfully design programs around these three methodologies in order to bridge the opportunity gap. If we combine Hypolite’s findings with the NEP’s actions to eliminate inequity in schools, we have a rich blueprint for prioritizing belonging and, thus, elevating our students’ STEM identities.

Supporting Educators in Fostering STEM Identity and Belonging

At Project Invent, my current role is to first and foremost support our educator fellows. In the day to day of things, this could be answering questions via email about an upcoming deadline, or helping to identify a component needed for an Arduino invention. In the scope of an entire program or school year though, my focus of support is driven by equity through STEM identity and belonging across all of our students. In any effort to improve student outcomes, I also recognize that burnout is real and many educators are facing over-capacity in their positions. As a program manager, my support is not just focused on invention but also where I can be a capacity-builder.

As a capacity-building support professional, I’m driven by adapting our program to meet the need of every educator in our community. I love solving problems, and this role allows me to be the coach behind challenges that teachers just might not have time to think about that day. Additionally, our curriculum is open-source, meaning anyone with a computer and internet access can download our resources and bring them to their youth instantly.

As a team, Project Invent program managers strive for our program to be adaptable to as many learning environments, youth, and communities as possible. Equitable implementation of our program should incorporate intention from our organization at every step of the fellow’s engagement, from first contact to Demo Day X. It doesn’t just mean how a fellow is using Project Invent in their classroom, but also which classrooms and communities get to have access to Project Invent in the first place.

How do we reach the youth farthest from opportunity, in the most intentional and equitable way?

There is and probably always will be vast opportunities for growth and improvement in equitable program implementation, especially within STEM. As an afterschool educator, this was always top of mind and what made our community so unique. We could capture more than the regular student interested in an engineering class, and even more so could support young people in ways that school communities could not. However, afterschool does come with access issues. Students who could not get to our site, because we weren't attached to a school, essentially could not participate. Conversely, students in schools who are taking a STEM program like Project Invent across a whole school or grade level may not have the capacity for individualized attention across students.

This is a huge question as we design and execute our fellowship recruitment. By providing fully funded fellowships for Title 1 communities (not just schools), we hope to capture interested and innovative educators in areas that aren’t typically funded for STEM programs. Beyond Title 1, the Project Invent fellowship is a sliding scale for programs and fellows from there. We also price by the educator, and not by the student count, so folks can adapt the size and scope of the program to as many youth as they see feasible. While this could have some drawbacks, like creating a barrier for youth not in a certain class or club, we are actively working with schools and districts to expand opportunities for any student to engage in Project Invent through our whole school model.

Identify and Invite Underrepresented Youth

Project Invent also provides professional development on supporting underrepresented youth in invention through our Summer Institute, and we have resources for recruiting youth from diverse backgrounds that start by communicating that they belong.

Drawing from my own experience from running Project Invent as an afterschool club, unattached to a school, when I was at the Gold Crown Foundation, recruiting diverse youth to participate was hard. As a new staff member, I focused much of my effort on researching the local community and finding every school within a five mile radius. Powered by my new professional Gold Crown email and lots of caffeine, I sent loads of outreach attempts to every school on my list. When I couldn’t get an answer, I called the front desk. When I couldn’t get anyone on the phone, I drove to the school with flyers. For weeks, I was terrified that none of my outreach was connecting to the students that wanted this program. But, as the days went on, I finally heard back from administrators, liaisons, and teachers—to my surprise! I was able to go to back-to-school nights and meet young people face to face, I presented in classrooms, and I had the support of school counselors to recommend students to the program based on need and interest. For two years in a row, the trickle was slow at first, but by the time programming started we had 20+ students from over 10 schools signed up and ready to begin.

Working with fellows as a program manager now, this is definitely a unique recruiting approach. Oftentimes at the beginning of the year or during the summers, we coach our fellows on identifying students outside the bounds of typical STEM students. We highlight the importance of recruiting youth from underrepresented groups relating to culture, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and identity to the Project Invent team, especially for elective courses and afterschool clubs. This typically looks like posting Project Invent flyers around campus, tabling at club nights, or working with counselors to spotlight the opportunity to students building their course schedule.

Add Cultural and Social Relevance

When recruiting students outside of typical STEM-identified folks, how can you grab their attention, speak to their interests, and capture their buy-in for the project? Make it relevant!

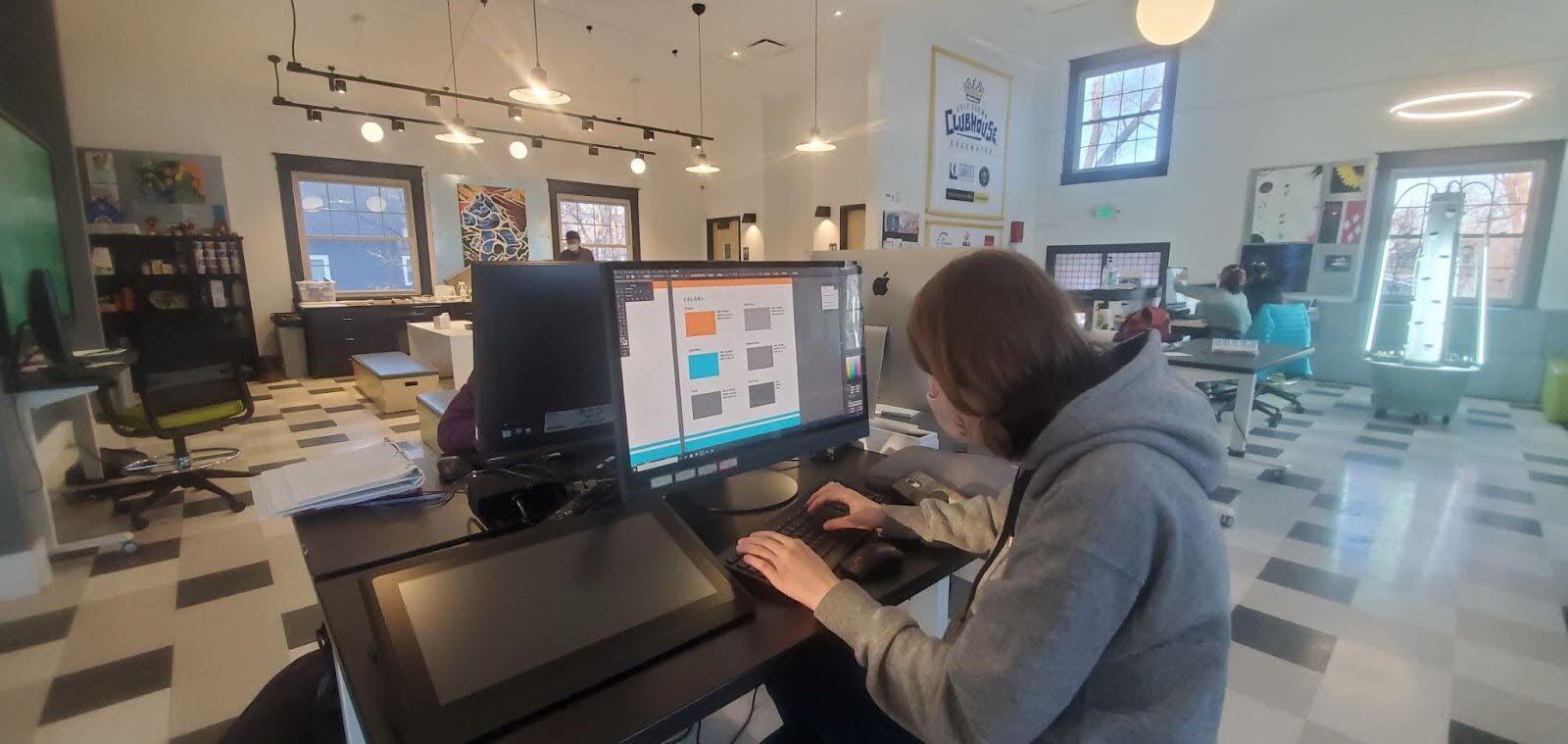

Another crucial equitable step in program implementation in Project Invent is to take time to plan the program around the unique needs of the learning community. With equity in mind, we support our fellows in implementing the program in a way that meets the needs of their youth. In my second year Project Invent team, we worked as a group to assign roles and responsibilities that aligned with students’ interests. These roles included CAD Engineer, Team Lead, Community Partner Liaison, and Software Engineer. Throughout my program manager role, I’ve seen some amazing team jobs in addition to these, such as Design Anthropologist, Business & Brand Manager, and Component Engineer.

Project Invent youth working as the graphic designer shown here building a color palette and branding guide for the team’s presentation.

We’ve also seen educators adapt Project Invent to fit into a specific course, like environmental science. In this case, our fellow found unique community partners that all had backgrounds in different areas of environmental science like geology, conservation, and astronomy. In another case, a fellow partnered with a business teacher colleague to develop a cross-curricular invention project. Cultural relevance, in addition to social relevance, is equally if not more important. Project Invent introduced a new, refreshed curriculum in Spring 2023 that includes a series called “Behind the Design” where each inventor shown in the curriculum is given a highlight. This is just a small example of incorporating cultural relevance into a STEM program. It’s important to not only share stories of STEM professionals that are representative of your students, but also learn and adapt to their unique cultural needs as an educator. The takeaway here is to take the framework of a STEM curriculum like Project invent, and remix, reuse, recycle, and redesign so it meets the accessibility, equity, and inclusion needs for your unique environment.

Make It Real

Students are more likely to continue with a project with engagement when they are connected to real people and real problems. In order to equitably bring STEM education to youth far from these opportunities, we must find ways to connect it back to our communities and the issues we face together.

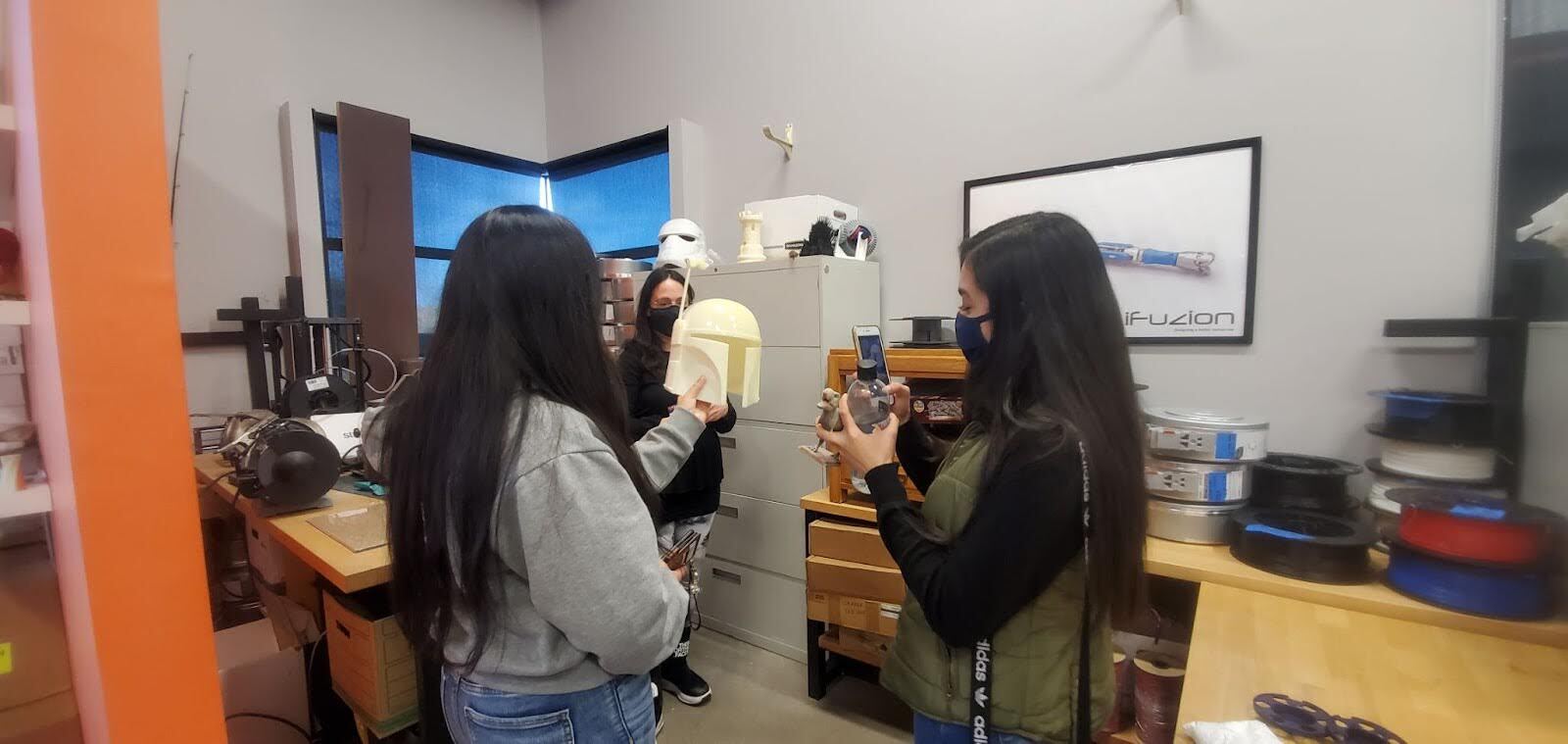

Project Invent team visiting a real-life prototyping lab in Littleton, Colorado. This is a great example of making it real for your students and showing them that the skills gained in Project Invent translate to real world experiences.

Project Invent takes this authentic connection to real problems as a cornerstone of our program. Inventors do not just invent a device, but they seek out people in their communities to design with, not for, under a liberatory design framework. Within Project Invent, there is a lot of flexibility in how to determine a community partner. For the case of equity, student participatory action in finding a community partner can be a huge motivator in capturing student interest. They may not want to participate in a STEM project for just any problem or any challenge, but they may want to participate if it's connected to their community. We see fantastic examples of this in our fellowship program every year. Students work with partners like state foresters, community gardeners, medical professionals, and experts in bike and pedestrian safety, climate change, and so much more. This is another strategy that helps attract students who may have not had exposure to opportunities in technology, but are drawn in by the prospect of supporting change in their communities.

Project Invent youth working with a forester professional Community Partner in North Carolina out in the field.

STEM Identity and Belonging Build Student Success Skills

STEM is not always everyone’s cup of tea. I get that, but I do genuinely believe that technology literacy is imperative for all young people to learn, and STEM programs generally help to accomplish that. Project Invent, for example, helps to accomplish that through the use of physical technology design. While I do not think that every young person needs to perpetually feel associated with STEM identity, they do always deserve to feel belonging. Everyone deserves a seat at the table.

And, the approach by which we accomplish STEM identity and belonging also builds youth’s future-resilient skillsets in ways that are unique. Skills built by programs like Project Invent include agency, resiliency, creative confidence, ambition, empathy, and curiosity—skills that are imperative to student success more generally. Not everyone will be a scientist, but we will all benefit from thinking like one.

As a STEM program provider, we have a long way to go with our other collaborators in order to bring true, equitable STEM access to youth across the country.

A Future of Equity in STEM

Overall, upon reflecting on the significance of STEM identity and belonging, it’s clear that initiatives like Project Invent are essential in equipping students with future-resilient mindsets and skills necessary to navigate an increasingly complex world. By leading with equity, we can ensure that all learners have access to the transformative potential of STEM education.

I would love to see a world where every young person has the agency to participate in Project Invent, every educator (out of school and in school) cares deeply about STEM access, identity, and belonging, and uses Project Invent as a tool to do more good, together.

Moving forward, there will be a continuous need for efforts to promote equity within STEM education as our world and technology rapidly evolve. It is imperative that educators and program providers alike remain committed to addressing systemic barriers and biases that hinder equitable access to STEM opportunities. Project Invent is a program that stands for leading with equity, and offers a pathway for students to uncover their passion for STEM, and make impactful contributions to their communities. By embracing a collective responsibility to promote STEM identity and belonging, we can empower the next generation of fearless, innovative problem solvers.

Sources Cited

Carlone, H. B., & Johnson, A. (2007). Understanding the science experiences of successful women of color: Science identity as an analytic lens. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(8), 1187–1218.

Hughes, R. M., Nzekwe, B., & Molyneaux, K. J. (2013). The single sex debate for girls in science: A comparison between two informal science programs on middle school students’ STEM identity formation. Research in Science Education, 43(5), 1979–2007.

Singer, A., Montgomery, G. & Schmoll, S. (2020). How to foster the formation of STEM identity: studying diversity in an authentic learning environment. IJ STEM Ed 7, 57 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00254-z

Shukla, S., Theobald, E., Abraham, J., and Price, R. (2022). Reframing Educational Outcomes: Moving beyond Achievement Gaps. CBE—Life Sciences Education Vol. 21, No. 2

Hypolite, L. I., & Rogers, K. D. (2023). Closing STEM opportunity gaps through critical approaches to teaching and learning for Black youth. Theory Into Practice, 62(4), 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/004058...

All photos courtesy of Project Invent.