Out of the Box - and Still Walled-in

Topics

Next generation learning is all about everyone in the system—from students through teachers to policymakers—taking charge of their own learning, development, and work. That doesn’t happen by forcing change through mandates and compliance. It happens by creating the environment and the equity of opportunity for everyone in the system to do their best possible work.

While EOC exams may be useful in high-performing schools with conventional subject-specific course formats, this strategy is less universally helpful and relevant for next generation school designs.

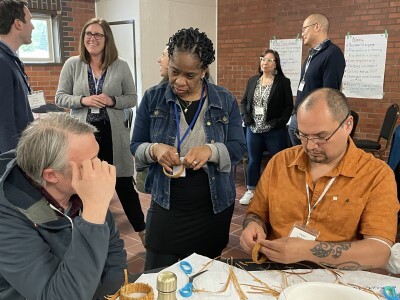

I’ve been checking in with our first cycle of Wave IV Breakthrough School Grantees as they prepare to open their doors to students this week and next. The news was good. The pace harried. Everyone is SO excited. As I listened, a few grantees shared a specific challenge on the horizon this year. “Our plan conflicts with the state accountability system,” is how one leader put it. “How so?” I asked. “Since our approach is interdisciplinary and project-based, we’re not teaching the conventional course structure for, say, biology or Algebra. Yet, our kids are supposed to take an End of Course (EOC) assessment in each of those subjects in order to graduate. The state requirements and our instructional approach are obviously misaligned. If we have to take all those assessments (in addition to our own)… it’s not going to go well. That would be a challenge.”

One school had applied for state (and through their district, federal) waivers, had proposed an alternative assessment strategy and not yet been told if it would be accepted. Ugh! I found myself feeling sympathy and frustration (and with some humility from my own days working in state policy). In my experience, policy makers at all levels act with good intentions but rarely create policies that are flexible enough to meet the wide variety of user circumstances that exists, and as a result, tend to generate barriers and unintended consequences. In this case, making EOC exams a requirement for graduation reinforces the traditional delivery model and will likely pressure many school leaders (and boards) to forgo more innovative options.

End of course exams were intended to enable students to show what they know closer to the time they learned it (instead of a one-time culminating graduation or exit exam). While EOC exams may be useful in high-performing schools with conventional subject-specific course formats, and perhaps in stimulating higher expectations in lower performing schools, this strategy is less universally helpful and relevant for next generation school designs. Next generation models often integrate content and skills across disciplines, may not organize learning around age and grade level progressions, and ask students to apply what they know holistically and collaboratively by solving problems with no “one” right answer.

“Given that you’re engaging students in such rich interdisciplinary learning, won’t they do well on these tests anyway?” I asked one of the next gen school leaders. “Not necessarily. These exams are like being tested in the technicalities of a single sport. So, no matter how athletic you are (like kids who play baseball, basketball and football), if that’s the only measure of success (now you’re being tested in golf), you’re not going to do well. You’d have to play and practice that specific sport every day to do well. Our state exams are like Jeopardy questions—full of discrete trivia.”

Next generation schools are committed to assessing student learning (see my earlier post or this one from national experts). Many use performance-based evaluative rubrics, manage online portfolios of student work and participate in national assessment programs (e.g., NWEA-MAP). Some of them are piloting the online Show Evidence tool and are breaking ground on measures of deeper learning. See my colleague’s earlier post about NGLC’s work on this.

Asking schools, teachers and kids to demonstrate what’s being learned is a reasonable expectation, and an essential component of any good learning model. Dictating one way for everyone to do it is probably not reasonable (or equitable, or smart given the preparation graduates need today and in the future). If school leaders can demonstrate a promising and thoughtful approach around performance, states should let them implement it (and thankfully, some do, although alternative proposals may still be viewed with skepticism or asked to meet a higher standard).

What assessments matter or are meaningful very much depends on how students learn, when they learn, and where they’re headed next. There are many paths to the same destination and at least as many valid measures of success. Providing some flexibility in requirements will allow—and even encourage—the diversity of learning models that students need and that we all want to see.

Next gen educators recognize that flexibility is an enabling factor for providing personalization and that our students need personalized educational strategies to be successful. In this case, schools and communities could benefit from a little more flexibility too—maybe from policymakers with a “next gen” mind set.