Professional Learning

Personalizing Adult Learning

Topics

Educators are the lead learners in schools. If they are to enable powerful, authentic, deep learning among their students, they need to live that kind of learning and professional culture themselves. When everyone is part of that experiential through-line, that’s when next generation learning thrives.

By using four key culture shift levers, one Boston high school developed a system of effective personalized adult learning.

The Bright Spot

Culture shift is a remarkably difficult task, but one which, as we move toward learner-centered education design, is absolutely necessary. Culture shift towards innovation-developing an agile organization that generates new solutions to persistent problems-is more difficult still. Chip and Dan Heath, authors of a variety of best-selling change management books including Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard, propose focusing on bright spots, places in a complex system where things are working.They suggest looking at data across the system and homing in on the places that produce unexpectedly positive outcomes under the same challenging conditions as the rest of the system.

Another Course to College (ACC),a pilot high school led by Headmaster Michele Pellam, is one of Boston Public Schools' (BPS) bright spots in shifting toward an innovative, problem-solving culture that focuses on closing opportunity and achievement gaps. The college preparatory school saw remarkable growth in some crucial data points in its school climate survey, administered to all BPS schools every fall and spring. In just half a year, from the spring of 2016 to the fall of 2016, staff agreement with the statement, "Leaders at my school seek out feedback from teachers," vaulted from 13 percent to 91 percent.

Other culture indicators showed similar leaps:

- "Teachers understand how our actions contribute to school priorities and goals"

- "My school leaders have a clear overarching vision that drives priorities, goals and decision making within the school"

- "My school leaders model the behavior they hope to see across the school community"

In addition, new BPS metrics like "I have a specific development goal or project for the coming year that excites me," and "The teachers who deserve leadership positions at my school are the most likely to get them" began very high under Michele's first semester of leadership.

Bright spot analysis urges us to start with the data and then dive ethnographically into creating context and color around that data-with the expectation of discovering levers that can be generalized to create change in other places. Through such an exploration of ACC, the BPS Office of Innovation, Michele, and some of the teacher leaders at the school have arrived at a story for the changes that happened there. The story tells of the inadvertent creation of a personalized adult learning system. We have also extracted some levers that may be used to shift culture to a problem-solving innovation mindset in other locations.

The Context

Michele Pellam came to ACC in the fall of 2015 after six years as a teacher at another BPS high school. As a new school leader and-compared to many of her staff-a relatively new teacher as well, she was highly sensitive to her role as a learner: someone who brought both strengths and as gaps to her new position and context. She actively engaged the school's faculty, many of whom had a long history at the school, in her learning as well as in a Central Office-aligned school improvement process.

ACC has a history of passionate, independent staff members, and Michele greatly respected this passion. She was also working under the vision of a new superintendent, Dr. Tommy Chang, who asked the 125 BPS schools, a third of which are autonomous, to come together in a common mission to practice equity, coherence, and innovation in order to eliminate opportunity and achievement gaps. Michele was tasked with adapting three core frameworks/tools that support this mission—Instructional Foci, Cognitively Demanding Tasks, and Culturally and Linguistically Sustaining Practices—to the deeply autonomous culture of ACC.

ACC is not unique in experiencing a tension between autonomy and coherence (or, in a more concentrated form, centralization); this story repeats itself in schools and school systems across the country at two levels: between teachers and school leaders, and between schools and central offices. Often, as the teachers below state, autonomy and coherence are experienced as opposing forces. Michele and her team's innovation was to develop a system of personalized adult learning that turned a possible dichotomy into a learning continuum.

Teacher Voices on the Tension Between Coherence and Autonomy

The tension between coherence and autonomy emerged as significant when the Office of Innovation asked teacher leaders at ACC to identify the main lever in shifting the school's culture toward collaborative problem-solving and, in cases, innovation. Teachers initially were wary of the move toward coherence, but as the climate survey numbers above show, that shifted very quickly, within a few months. Johanna Waldman, STEM Lead Teacher, writes eloquently about this shift:

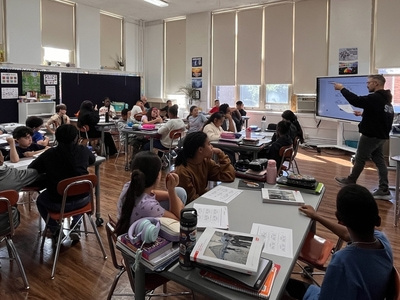

Teacher autonomy has always been an important foundation at ACC [though]...[t]he shape of this autonomy has ebbed and flowed... What I think has changed...under Michele's leadership, is the evolution of structures that provide cohesion and support, while still prioritizing and encouraging teacher-led goals, work, and projects. Though there are clear foci, based on district and school priorities, teachers are able to craft individual goals that link to those focus areas. In addition, our professional development is both more aligned to those common goals and to that sense of individual development. Rather than looking externally, we are sharing and supporting one another internally. Teachers have targeted conversations about daily practice and the pedagogy in cohorts led by cohort leaders that are colleagues. Then we also meet as a full staff and in departments to self-assess, reflect, and discuss on practices related to the common goals. We also are working on systems to share internally-both data about what and how we are doing as well as best practices.

Marina Gopie, a new English Language Arts teacher, shares her perspective on the same experiences:

At the beginning of her first year, Michele asked what we needed to be successful in the classroom. I shared with her that I felt isolated as a new teacher. When I first interviewed at ACC, I was asked why I wanted to work there. I recalled my experience as a student and expressed that it was the "spirit" of the school that drew me to it. As a student, I felt safe and supported at ACC. We were a close knit community. I wanted to feel that way as a teacher. ACC is more interconnected now because Michele has made collaboration and interdisciplinary work a priority. She celebrates everyone's accomplishments and highlights varied teachers' work during weekly staff meetings. Giving us a glimpse into classrooms that were once so separate has brought us together through curriculum and ideas. New teachers see this collaboration and it has become part of our climate at ACC.

Michele and the distributed leadership team she resourced at ACC were successful in creating a culture of coherent personalization. Coherence was seen as enabling autonomy rather than diminishing it, and coherence also created community. Professional practice goals allowed teachers to pursue their passions in ways that led to innovation.

Seamus Foy, an English Language Arts teacher with 15 years' experience, identifies the key lever in the culture shift as "having the space and support to pursue an idea." He continues,"A lot of us are testing ideas, sharing our findings, and learning from each other." Seamus's innovation is designing a school program that would take urban high school students out into nature all day every school day for an entire semester to learn through their engagement with the natural world.

At ACC, Michele took what could have been experienced as top-down central office mandates and instead deployed them to create space for both community-peer learning networks-and individual growth-passion projects-within a common vision. These networks and projects in turn led to innovation to improve the school.

In other words, in six short months, Michele enabled personalization of adult learning. The Office of Innovation, Michele, and the teachers above collaborated to develop a list of key culture shift levers that she deployed to move ACC toward personalizing adult learning.

Culture Shift Levers for School Leaders

- Develop vision conversations: what non-negotiable competencies are we moving towards and where do we commit to freedom to personalize?

- Be a learner: be willing to be vulnerable and not have all the answers

- Be an opportunity-maker who grows capacity: look at budget and find reallocation opportunities in order to resource distributive leadership; create tangible roles for teacher leadership and enable teachers to get certifications, credentials, etc. necessary to take on those roles; create space, time, and funding for teacher passions

- Be a connector: enable and celebrate peer learning

Next Steps

Michele sees herself as a learner among other learners as do ACC's teachers. According to Seamus, "half the staff [is] actively working on an innovation that contributes to improved teaching and learning at ACC." And the innovative passion project Seamus spent his professional growth time developing is being implemented in partnership with BPS's Office of Innovation as a semester-long expeditionary learning program that all ACC juniors (and some students from two neighboring high schools) will participate in beginning in January 2018. In the upcoming school year, the BPS Central Office and ACC administration, teachers, and students look forward to learning together.