New Designs for School

Project-Based Learning: Necessary but Insufficient

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Project-based learning is phenomenal. But it is not enough. Thrive has developed a way to integrate learning discrete skills without losing the magic of PBL.

The best projects share a set of qualities:

- Projects align to the content and standards of instruction.

- Projects are backwards planned, toward a specific outcome, with gradually more difficult, and more independent checkpoints leading up to a final, independent product.

- It bears repeating: Each individual student is accountable for his/her final product.

- Projects are conducted over a sustained period of time, and in their completion, students both learn and demonstrate their learning.

- They are interdisciplinary to some degree.

- Projects require students to engage in and with research.

- Projects require students to use technology beyond what’s typical in the classroom. This may mean learning how to stretch a canvas and gesso it; this may mean learning how to collect data on a polling app.

- Projects connect students to the world outside the classroom.

- Projects require (at some point along the way) for each student to lead other classmates and to follow them.

- Projects are, by their nature, infinitely differentiable and encourage student agency, voice, and choice.

- Projects have common baseline expectations but a variety of successful outcomes.

- Project presentations make students publicly accountable to strangers, and require them to “code switch” into a specific mode of presentation (professional, casual, academic, in-character).

- Projects inspire, connect, challenge, and elevate students.

- Projects result in beautiful work.

The Power of Project-Based Learning

There is nothing more powerful than a highly engaging project to help students connect to the real world, collaborate passionately, and apply new skills to unfamiliar circumstances. Our students evince this.

Two students, who tend to work only about as hard as they have to, stare at what they will later refer back to as that “hideous, hand-made, inflatable raft,” with a new appreciation for measurement and an attentiveness to aesthetics.

Another, let’s call her Vanessa, stands alone, in the center of a stage she helped build. An audience of family, friends, and students in the three grades above her rise to their feet to applaud the three-minute soliloquy she wrote, directed, and finally, performed.

We can’t say it enough: we love Project-Based Learning. We’d be hard pressed to find anyone who doesn’t find its impact on students riveting. As a direct outcome of our combined careers, there are over 1,000 young people in Southern California who know how to turn research into art and who can speak their truth in a public space. Talk about job skills in our current market of Ted Talks and Kickstarter.

This is what Project-Based Learning does. It’s phenomenal. It’s life-changing. But it is not enough.

As long-time PBL teachers, we are as much critics of projects as cheerleaders for them. Our work over the past decade has been to explore ways in which schools can address what we have noted as the shortcomings of PBL—mainly that to our chagrin, many students move through projects unaware that they are missing important content-specific details and skills—without losing the magic.

The Shortcomings of Project-Based Learning

Projects are great at building critical thinking and creativity. They put students in the center of the work as decision makers and teach them the power of productive struggle and revision. But projects don’t always lend themselves to the scholarly practices needed for math fluency or the rote training needed for grammar mastery.

Let us pause here for a minute and affirm that we believe the skills learned from PBL (even and especially when projects are imperfect) are more critical than any discrete content skill, but that doesn’t relieve our responsibility to our students’ literacy and numeracy. Educating young people is a complex process and we believe that no single learning modality is sufficient in preparing our students for the future.

Let’s zoom in on Vanessa and her classmates, each delivering their 9th grade ELA final projects to a public audience—and masterfully. We ran this project for three years and the result replicated itself: 100% participation, increased confidence, increased literacy. And each successive year, we watched with heartbreak as some of them as 10th graders failed the CAHSEE, a basic skills assessment.

These students could argue the validity of a source but not identify academic vocabulary in context. They could design, measure out, and construct a platform stage, but not solve a simple geometric proof using deductive reasoning. The discrete content skills they lacked were not emphasized in the curricular approach we were following in our PBL classrooms. But identifying vocabulary in context and conducting logical arguments are skills that make learning easier. Ultimately, these skills can be taught in short bursts of direct instruction, peer-practice, and iteration.

Simply put, we believe there is a need to teach and assess literacy and numeracy for breadth and fluency and we recognize that projects are notoriously inefficient in these areas. Think back to lists we memorized as children. We are walking encyclopedias of rote information that serves us even now in our daily lives: the alphabet, colors, days of the week, right/left, counting by 1’s, 2’s, 5’s, 10’s. We learned these skills by repetition, songs, memory games, and association.

At Thrive, and schools like Thrive, we acknowledge that critical thinking requires a vast foundation of factual building blocks, a foundation that asserts that the deepest learning occurs when a student’s knowledge base is put to use in strategic problem solving. While there’s a teacherly joy in dreaming of an eight-week project exploring the concept of “blue” or the beauty of “7,” we have to acknowledge that to study a breadth of foundational concepts at PBL pace would be a disservice to our students’ need for background information and core content.

Learning Discrete Skills in Project-Based Classrooms

So how do we do both? How do we blend PBL with our current classroom practice (or in reverse, how do you supplement PBL with the learning of discrete content)? We propose this planning process. Such a plan emphasizes a learning structure for both the acquisition of basic skills and the application of that content to a high-stakes, real-to-life project.

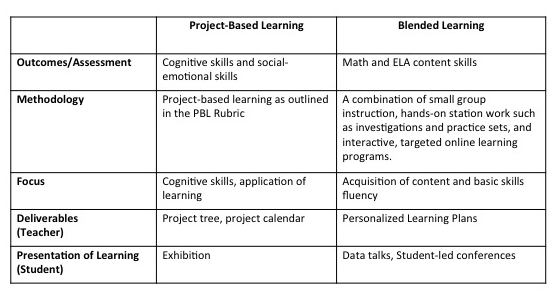

Of course, there’s a lot more to course planning and instruction than a quarterly outline. We have to decide how to deliver the content (Will we use direct instruction, online learning programs, investigations, etc.?) and we have to adjust for what really ends up happening in the classroom. This table outlines how we view the methodology of blended learning aligning with project-based learning across several dimensions to promote the learning of discrete content skills.

Good teaching, as the axiom goes, occurs when educators have a full toolkit, when they use the best of what’s available to them to ensure their students are learning. We hope the resources in this post add to your toolkit.

- Teacher-Created, Teacher-Led Professional Development on PBL (slide deck with embedded resources)

- PBL at Thrive: The Gift of Flight (video)

- PBL at Thrive: The Strength of Structures (video)

- #NGLCchat: Project-Based Learning, Thursday, September 15, 2016, 7pm ET. Join us and other PBL educators to learn together during this Twitter chat.