How to Address Racial Bias in Standardized Testing

Topics

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

COVID-19 has disrupted springtime testing; now is the time to ask why we use standardized tests, considering the racial bias in them.

As a high school student, I associated spring with sitting in a crowded classroom filling out bubbles on a test. In a normal year at this time, high school students would face a barrage of exams including the SBAC, AP testing, the SAT, and the ACT. But like the economy, healthcare, and our social fabric, COVID-19 has disrupted the education system, including the practice of springtime testing.

Given this temporary relief from testing, now is as good a time as ever to consider why we administer standardized tests, particularly when we consider the racial bias in these tests. How are standardized tests unfair to Black and Latinx students?

Stereotype Threat

Racial bias in standardized testing shows up in multiple ways. First, Black and Latinx students face stereotype threat. Psychologists Joshua Aronson and Claude Steele have researched how the additional stress of negative stereotypes about students of color and their intelligence manifest in lower test scores. The fear of confirming a stereotype of inferiority creates stress and anxiety that contributes to poor test performance.

Some suggestions to mitigate the impact of stereotype threat on test performance include telling students not to fill out demographic questions on the test, asking students to think of areas in their lives where they are successful, and emphasizing growth mindset—the idea that all students can, in fact, improve their performance through hard work.

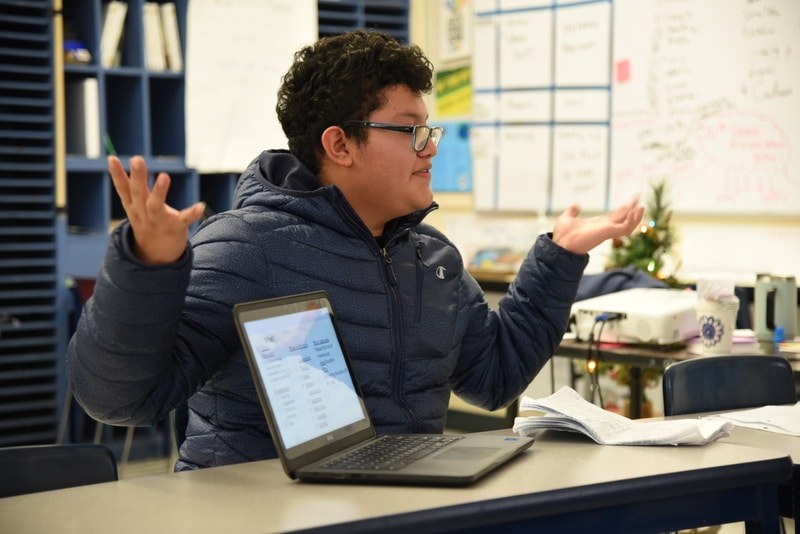

(Courtesy of Young Whan Choi)

Racial Bias in Standardized Test Questions

Standardized testing poses another threat to historically marginalized students; these tests are often designed with racial, cultural, and socio-economic bias built in. I remember proctoring the now defunct California High School Exit Exam to my 10th grade students. I believed that I had prepared them well to write proficient five paragraph essays, but doubt crept in when a student called me over with a question. With a puzzled look, she pointed to the prompt asking students to write about the qualities of someone who would deserve a “key to the city.” Many of my students, nearly all of whom qualified for free and reduced lunch, were not familiar with the idea of a “key to the city.”

Too often, test designers rely on questions which assume background knowledge more often held by White, middle-class students. It’s not just that the designers have unconscious racial bias; the standardized testing industry depends on these kinds of biased questions in order to create a wide range of scores. Professor James Popham, a renowned educational testing expert, put it this way, “One of the ways to have that test create a spread of scores is to limit items in the test to socioeconomic variables, because socioeconomic status is a nicely spread out distribution, and that distribution does in fact spread kids' scores out on a test.” (Frontline, PBS, 2001).

Ironically, if Black and Latinx students started to perform as well as their White and East Asian peers on these tests, then the tests would be meaningless to colleges. They could no longer use test scores to differentiate among applicants.

Equitable Assessment Tools

While much has been said about the racial achievement gap as a civil rights issue, more attention needs to be paid to the measurement tools used to define that gap. In other words, education reformists, civil rights organizations, and all who are concerned with racial justice in education need to advocate for assessment tools that don’t replicate racial and economic inequality.

Where standardized tests consistently reinforce a racial achievement gap, OUSD students experience the capstone project as a bridge over and beyond that gap.

Thankfully, some educators are using performance assessment tools like portfolios, public exhibitions, and capstone projects in ways that foster a positive exploration of identity and that encourage a growth mindset. I saw the power of this kind of assessment for Black and Latinx students at Vanguard High School where I first taught over twenty years ago. The school had a waiver from the New York State Regents examination, and students demonstrated learning through oral presentations of their knowledge. After reading Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, students explored topics like whether race relations now are worse or better than during Ellison’s time. Students’ work and the school itself had to pass an external review by the New York Performance Standards Consortium.

But, unlike a standardized test, when students came up short on the rubric that defines quality, they received direct feedback on areas they needed to improve and had an immediate opportunity to revise their work to achieve proficiency. This opportunity for revising work is critical. It signals to students that they can improve with additional work and that they are, in fact, expected to do that work. Growth mindset lives at the heart of these kinds of performance assessments.

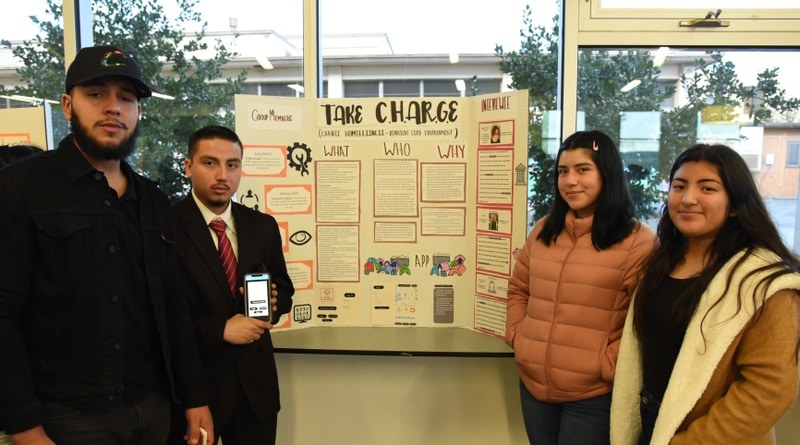

(Courtesy of Young Whan Choi)

Performance Assessment in Oakland Unified

My experience at Vanguard has impacted how I lead the work around performance assessments in Oakland Unified School District (OUSD). We have a set of common rubrics that we ask schools to use to evaluate their students on a graduate capstone task. By receiving scores on these rubrics, students can clearly see where they need to improve in order to cross the threshold for passing. All schools implement scoring early enough that students have time to revise.

Unlike standardized tests that intentionally include questions biased against students of color, the OUSD capstone task begins with students’ interests. They pick a problem in the community that they are interested in and then write a research paper on promising solutions to that problem. Often students choose questions that relate to their identities or a defining experience in their lives. Here are a few of the paper topics:

“Should We Use Urban Gardens Instead of Agribusiness in California”

“Promising Solutions to Address the Impact of Gun Violence on People’s Health”

“How to Address Wildfire Smoke at Skyline High School”

At the end of 2018, more than 1,200 seniors completed a survey about their experience with the capstone project. Seventy percent (70%) reported that the project was valuable or very valuable in strengthening their oral presentation skills. The most remarkable fact about the data is what we see when we disaggregate by race and language proficiency.

Where standardized tests consistently reinforce a racial achievement gap, OUSD students experience the capstone project as a bridge over and beyond that gap. For example, Black, Latinx, and English language learners report at higher rates that the capstone project is valuable or very valuable in strengthening oral presentation—73%, 74%, and 77%, respectively. This positive trend holds true in all areas we assessed—research skills, writing skills, and being a proactive learner.

Performance assessments, like OUSD’s capstone project, are just one part of addressing racism in the educational system. We have become overly reliant on a system of standardized testing that continues to produce the results it was designed to get—a spread of scores that maps neatly to race and socio-economic factors. These test scores, in turn, justify closing schools in poor communities of color and barring Black and Latinx students from educational opportunities, and thereby, from jobs that support a middle-class life.

(Courtesy of Young Whan Choi)

COVID-19 has caused disruptions around the world and in every area of our lives. In these moments of uncertainty, we are seeking new ways of being and acting. At some point, hopefully soon, when the pandemic ends, I look forward to some aspects of life as I had known it—enjoying a night out with friends, offering hugs and handshakes, and convening teachers for professional learning. I hope, by contrast, that we don’t return to our usual practice of standardized testing that unfairly disadvantages Black and Latinx students. Instead, let’s use this opportunity to commit to more racial justice in education by creating an assessment system that supports the growth mindset and identities of students.

For another perspective on addressing a history of structural racism through performance assessments, read Lisa Martinez of Future Focused Education's article on designing anti-racist senior capstones for New Mexico communities.

Photo at top courtesy of Young Whan Choi.