Technology Tools

Reengineering Classroom Dynamics

Topics

Educators often take advantage of educational technologies as they make the shifts in instruction, teacher roles, and learning experiences that next gen learning requires. Technology should not lead the design of learning, but when educators use it to personalize and enrich learning, it has the potential to accelerate mastery of critical content and skills by all students.

What if there was a way to read students’ minds to know who has something to say? (Spoiler alert: there’s not.) But it IS possible to use their own words to bring them out of their shell.

There’s a famous scene in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off where teacher Ben Stein calls out names in the hopes that someone—anyone—will answer his question. The camera pans across a roomful of bored students, their eyes glazing over as he repeats ‘Bueller?’ for the third time in a row.

Sadly, much of the reason why this is so funny is because it’s so relatable. Nearly everyone has had an experience like this.

Now think back on your college classes. Maybe you were in a small room, or perhaps in a giant lecture hall. Either way: did you tend to participate often, or did you do a lot of listening?

If you were quiet, you’re not alone. According to the New York Times, a growing body of evidence suggests that a variety of cultural factors shape the college lecture—and more specifically, who participates.

No matter the cause, the situation is unfortunate. In my experience, I have encountered many ‘wallflower’ students: those who avoid eye contact with the professor, who don’t eagerly raise their hands, and don’t volunteer to share their perspective. These folks are missing out on contributing. It’s important to note that while they’re not comfortable participating on their own, they’re not necessarily content with absolute silence, either.

Beyond that, the class is missing out on hearing their thoughts.

So what happens when in-class discussions lag? You have few options, really. Most professors will either call on those willing to speak up, or attempt to bring others into the conversation at random.

While this might generate discussion, it is 1) unlikely to bring the less talkative students to the forefront of the conversation, and is 2) truly only a temporary solution at best. Providing encouragement and offering feedback is important, but again, these things alone often don’t solicit substantive commentary.

What if there was a way to read students’ minds to know who has something to say? (Spoiler alert: there’s not.)

But it IS possible to use their own words to bring them out of their shell.

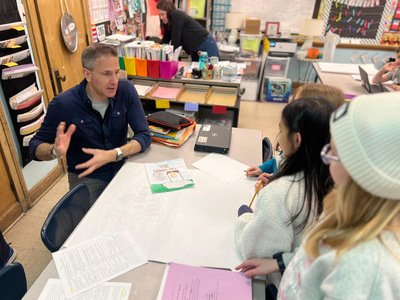

Initially, I created ForClass to encourage more robust conversation among my own students. Because the system enabled me to visualize students’ answers to qualitative questions, I could use it to my advantage. Knowing from Maria’s pre-class assignment that she had not only agreed with her chattier classmates Kevin and Kate, but had elaborated on their ideas, enabled me to lead her into what would become a much more insightful conversation with her peers.

As a professor, I didn’t have to increase my prep time or memorize students’ responses—who agreed or disagreed with whom, or challenged this particular point, and so on. I had the information right at my fingertips when I needed it, along with students’ names and photos, making my life easier and students’ learning experiences much richer.

As a professor, I didn’t have to increase my prep time or memorize students’ responses—who agreed or disagreed with whom, or challenged this particular point, and so on. I had the information right at my fingertips when I needed it, along with students’ names and photos, making my life easier and students’ learning experiences much richer.

As both an educator and a co-founder in a start-up, I know firsthand the market I’m serving, and have personally reached out to hundreds of faculty members who have been searching for ways to make class a livelier, better environment. Many of them are using ForClass today.

And many of them have shared with me a common reaction among a collective population of 25,000 students: we call it the ‘gasp moment’. Students tend to gasp aloud when seeing their name and photo accompanying a graph with answers to questions.

After the surprise wears off, however, discussion becomes much more of a level playing field—and the wallflowers are abandoning the role of spectator.