New Designs for School

Speak, John, Speak: Feeling the Power of Exhibitions at the Workshop School

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

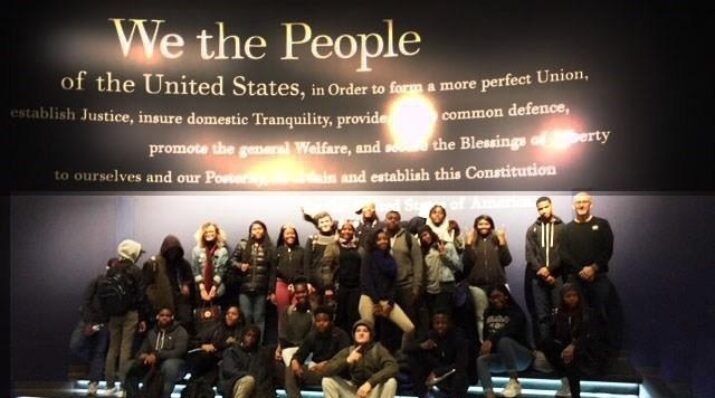

Like many progressive schools, the students at the Workshop School, a non-selective high school in the School District of Philadelphia, present their work at the conclusion of each quarter.

Like many progressive schools, the students at the Workshop School, a non-selective high school in the School District of Philadelphia, present their work at the conclusion of each quarter. By the time their sophomore year ends, they’ve presented eight times. Sophomore year finishes with the Gateway project, where they declare which of the upper houses they’d like to try: internship, college, construction, or shop. We emphasize the equality between these pathways so that the kids understand the resources and quality of teachers are the same; what matters is the choice made by the student as they try to figure out what they want to do and why. During our eleventh and twelfth grade years, they continue with presentations so that by the time they graduate, they’ve done sixteen exhibitions. There’s a weariness that accompanies the pride of completion each quarter, but there’s also a comfort with presenting that has become a hallmark of our program.

Keeping Exhibitions Fresh and Powerful

Teachers at any level can dread exhibition weeks: the focus of listening closely to presentation after presentation wears you out. And no matter how powerful the culture you’ve built with your students, it’s hard for any group to watch twenty-six presentations over four days. As the days go on, the comments diminish and the kids struggle to stay on point. This year the junior and senior students of our advisory brainstormed solutions and we framed the exhibition days out this way: two days of watching, giving feedback, and keeping an exhibition journal. One day of supporting younger students, mostly tenth graders, as they worked through their first exhibition of the year. And one work day to assemble work or to polish or complete any last deliverables. This process made the week flow better and led to greater concentration during most of the presentations.

Reflection: In terms of the teacher products from these days, I create a letter that I send to all students at the end of each quarter upon which I’ll add my own thoughts; I usually keep an email open that I add points and questions I want to talk over with the students. Students keep exhibition journals where they provide feedback to each other, write down quotes (thanks to DD for showing us the way), and reflect on what they’re seeing*.

Audience: Parents are an expected part of this process, although as the students get older, we tend to leave it up to students to invite their people. I called a few parents to ensure their presence although many came on their own. A typical audience, then, consisted of fifteen students, one or two relatives (unless it’s KS, in which case he brings every single one of his aunts and livestreams it for the relatives who haven’t come), one or two additional staff members from the school (this year my boss’s boss and another thoughtful staff person attended the exhibitions), a few students from the course I teach at the University of Pennsylvania, and, more often than not, one or two visitors from the community.

Student-led: Students introduce each other and set the norms for the presentation. With constant guests, though, I’ll ask the person doing the introduction to explain the purpose of exhibitions (I make a living annoying my students with the “why are we doing this” question.) AG introduced a peer by declaring that in exhibitions, “instead of the teacher telling us what they taught, we talk about what we learned.”

Capturing Wisdom

Small bits of wisdom make their way onto a wall of student quotes in room 201. Here’s one example from a wonderful exchange between two students during an exhibition which also shows the humor that is necessary to get through this important but intense week.

JJ: “How have you lived up to the four words (the ideals of our classroom)?”**

AG: "Ever since I was able to talk I've been collaborative"

Just as humor carries us all through exhibition weeks, close attention to the text of the presentations allows key insights into student progress as well as the culture of the class and the school. I will gather three to four lines from each presentation to use as starting points for future conversations in our room. This blog post is an extended version of this process, so what follows is an example of our notes from a presentation by JY. When you have a good community like the one in 201 you could write a different dissertation every day, but special thanks go to JY for being JY.

“You won’t always get justice but at least you’ll be heard.”

This was JY talking about the end of a project, about why they’d taken it on, and about the impact. One thing we emphasize above almost everything else is that students are able to explain why they’re doing what they’re doing, whether it’s a small activity at the beginning of a week or a final culminating project. At least in my space, students have taken to asking, in a jeering yet loving way: “Yeah, how does this project change the world?” As a way of capturing the drive toward justice and a set of projects, this is a non-cynical, thoughtful way of capturing a project’s goals.

“Making honest money.”

There’s a near constant tension in most urban schools. American poverty is everywhere and the structural realities of most students’ lives create potent obstacles to their education and, let’s be real, direct threats to their lives. We can talk about this reality, we can study it and make it the focus of projects, we can try and foster the skills and the, sigh, “grit” necessary to make honest money. We’re not remaking American labor markets and we’re not foolish enough to think we can, but we do hope we’ve empowered kids to try and find their own way through a difficult landscape.

“I don’t only have to help the place I come from, I can help people everywhere.”

This was a direct response to feedback offered by a community visitor to our place. After another student had presented, the commenter noted that you could try to help everyone not just yourself. There had been some discomfort in the room—nothing like an old guy in a suit with his fortune made urging students to be altruistic—but I was proud of this response.

“I gotta work extra hard to get these things down pat, things I shoulda got in middle school.”

We are constantly trying to empower kids by highlighting what they might need in the future. We try and do this in a different way—we want them to see the need of a skill or a body of knowledge by completing a project that does work in the world—as opposed to bludgeoning them with their own gaps the way most schools do. If all goes well, students develop this sort of self-awareness and the strategies they need to keep in mind as they attempt new projects.

“Building ideas on a prototype will get my brain working.”

“Making a model will help me actually engage, make my brain more engaged.”

For all the schooling-by-design talk, for all the clever graphics about the design iteration process, for all the talk of STEM and STEAM and every other reform, these quotes show how JY gets inside of a project. This consciousness about a work process, a cycle, a way of taking an idea into the world, slowly, with half-steps and missteps, of thinking about how to get your brain running...it’s all bound up in these comments.

“I try my best, my best, my best, to be a part of the community.”

I loved the purposeful, intentional way JY described his role in the world of room 201. This is not an easy task. We have twenty-seven powerful individuals in a vaguely industrial room for four hours. What work do we all have to do to make a community that supports quality projects? What work do we have to do to make sure everyone can be their best selves?

“This was me motivating them.”

JY presented several pictures showing himself interacting with his peers. Only one was clearly staged.

“Work ethic of an African.”

JY was talking of his boxing prowess at a local gym, where they refer to him as “Little Africa.”

Racial and ethnic identities constantly emerge as a topic in our room. Students claim different perspectives, play with them, and talk of them. KH greets me often with “Good morning, white man.” It’s this playful talk in a safe space, a space that we build and protect together through constant work. More importantly, that work allows us entry into the more serious undercurrents of race, class, and gender that affect our school and our ability to do projects. JY’s identity as a boxer is shaped by how the people at the gym see him and his pride in this identity.

“He died this summer.”

Southwest Philadelphia can be a hard place. This presentation saw JY demonstrating the kind of engagement with work we want for all kids. This presentation saw JY demonstrating the kind of self-awareness that any good education ought to foster. This presentation saw JY provide evidence of how he integrated academic and social skills. Yet this presentation ended with a reminder of all the losses, the trauma, and the inequality that shape the lives of too many children.

JY shines brightly. May he continue to do so. But it’s the world we’ve all made together at the Workshop School in these exhibitions that make his presentation possible. JY is one of 26 impressive students in room 201 and their words ring with power each quarter.

*Note: This article was shared with and edited by the students of room 201. All names have been initialized. We welcome visitors who want to continue these conversations.

**Our four words for this year were persistent, collaborative, professional, and motivational.