Reimagining Assessment

State Assessment Results: Go Low or Go High?

Topics

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

State assessment data can be used to limit student opportunities or expand them. Promoting continuous improvement can make the difference.

Every year newspapers across the nation rush to print the results of schools’ annual academic achievement on state exams. These stories are almost always published with much fanfare in stunning color, above the fold, pushing current national and local politics to the side for a few days. The publication of these results are often received with mixed emotions by parents, administrators, school board members, teachers, realtors, and community members—each group using the results for very different purposes. Parents look to the scores to confirm their commitment to their child’s school or to pick a school. Administrators and school board members use the results as a tool to drive their goals and decisions. Teachers, more often than not, dread the results because they never seem to have the time to cover all of the curriculum by the end of the year. Realtors jump on the scores to play up the value of the houses and neighborhoods. Each group is faced with a choice of how to view these data. Should the data be used to go low or go high?

"If my future were determined just by my performance on a standardized test, I wouldn't be here. I guarantee you that.”

–Michelle Obama

Go Low: Limiting Student Opportunities

All too often individuals and groups fall into the trap of seeing annual, standardized assessment results through a negative lens. What I mean is that the results of these tests often lead to a confirmation of negative stereotypes or preconceived assumptions about individual students, groups of students, or schools. State assessments are autopsies—reflections on a day or two gone by that will never come back. The results of these assessments often reinforce the socio/economic and linguistic status of the student body.

Think about it: if you were given a high stakes test in a foreign language, even if you had completed multiple courses studying that language, it would not fully define your academic achievement or ability. Still more, if you were given a high stakes test based on the academic nuances of a foreign country, you might understand some of the content, but would likely get many of the nuances wrong, not from lack of intelligence or achievement but because the test was designed based on a particular cultural experience.

I am not just referring to the challenge the student immigrant population faces when taking state content assessments. I am also referring to students with a variety of ethnic, racial, and socio/economic backgrounds. For students from populations that are not white or middle class, state assessments might just as well be from a foreign country—often infusing content, vernacular, and nuances that take generations to master, not years. So, when state assessment results are used to make judgments and decisions about students in isolation of other information, it takes education low: robbing students and teachers of the much needed space and freedom to create environments that focus on developing the capacity and confidence tucked inside of every student.

Dr. Amanda Datnow, Professor at UC San Diego and a member of the International Center for Educational Research & Practice (iCERP) Action Council, highlights in her research that all too often state assessment results or other end of term assessments can be used in isolation to direct educational moves that limit students’ opportunities. Specifically, Datnow and Park, in an article in the Journal of Educational Change, point out that this approach can often close doors for students.

Examples of this practice include narrowing the curriculum around accountability measures, using assessment data to rationalize track placements, and focusing on a narrow band of students. This process of closing doors on students becomes an issue of equity and access.

“If you want to increase student academic achievement, give each student a friend.”

–John A.C. Hattie,

Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning

Go High: Expanding Student Opportunities

On the other hand, state assessment results can play a positive role when they are part of a balanced assessment system. Similar to decisions we make in our daily lives, decisions about achievement should be guided by multiple data points. Something as simple as going to work requires a series of data points to arrive with success–time, weather, traffic, day of the week, clothing options, family obligations, etc. Some of these data points are long cycle, like the date and time of work days; others are based on short cycle data, gathered by the hour or even minute, like weather or traffic. By using a suite of data, we are able to get to work consistently without incident. If our success at work were based on a single assessment at the end of the year, how different would our work experience feel?

Using state assessment results as one measure in a suite of multiple measures brings education to a higher place–one that sets the stage for a culture of continuous improvement. This approach shifts the locus of control to students because they now have time and space to demonstrate their learning using a variety of data points from annual, to semester, to unit, to daily, to minute by minute.

If we shift the intent of the state assessment results away from a judgment tool then the data can be seen from a different perspective, one that can open doors for students. Referring back to Datnow and Park’s research, the thoughtful use of data to inform instructional decisions and actions expands opportunities for all students. Specifically, using a variety of data can begin to challenge our beliefs about individual students and student groups rather than confirming our assumptions.

This research-based approach promotes an equity mindset that broadens opportunities for students to demonstrate their achievement in novel ways that align to their individual strengths and interests. Teachers use these data to shift into an activator of learning role, providing ongoing feedback to students for the purpose of continuous improvement. Students, engaged in an environment of improvement, begin to see assessment as an opportunity to shine.

Moving to Action: Promoting Continuous Improvement

Adopting a mindset that opens doors for all students is not that hard. The iCERP Action Council is working directly with site administrators in Vista Unified School District to design and implement tools that set the conditions for teachers and staff to use data to inform their teaching and support. Specifically, iCERP Action Council members Jennifer Peirson and Amanda Datnow designed a Cycle of Continuous Improvement Data Discussion Tool based on the cycle of instructional improvement: 1. Set goals and align resources, 2. Gather and share data, 3. Analyze data, 4. Use/act on information. Using a tool like this consistently across an entire school district can really transform the school experience for all students.

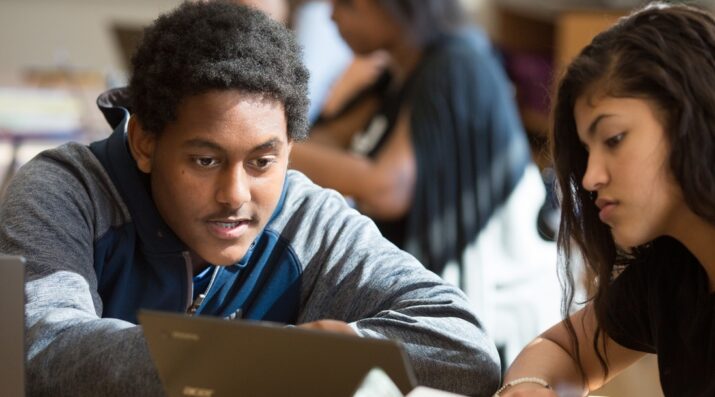

Photo courtesy of Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action.