New Designs for School

What Does Italian Cooking Have to Do with Strengths-Based Learning?

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Stories of learning approaches that tap into students’ strengths, gifts, interests, passions, and future goals

There has been a lot of backsliding happening in the world of education policy and practice these days since COVID. I had hoped for the opposite. We learned so much from COVID about how teaching and learning and the organization of school could be different, and as I’ve written before, about healing, and what students so genuinely and maybe naively expected to see coming back to the school building after a year or more of virtual learning. But sadly now most of what we hear is at best about “learning loss” and how to “catch up” or “accelerate learning,” and at the worst, so much political manipulation and fear-based criticism of even the most fundamental positive changes we’ve made to bring the learning experience into the 21st century—SEL, the science of learning and development, trauma-informed practice, deep equity work, mastery and competency based learning vs. seat time and traditional grading, performance-based assessment, experiential learning and work-based learning outside the traditional classroom, student voice and agency around addressing real world problems, etc. We need to slow down, stop this incessant, instinctive, and frenzied reaction to double down on more and more content. That is, we need to be constructivist teachers, not consumerist teachers. We need to recognize where our learners are now as whole people who actually want to learn, and recognize their assets, their strengths, gifts, interests, and passions as well as their needs for emotional support and connection. And slowly, slowly, we need to build the learning ecosystem from the foundations up; that is, we need to do it right from the beginning, or we’ll just have to do it all over again later. As adrienne maree brown says, “There is always enough time for the right work.”

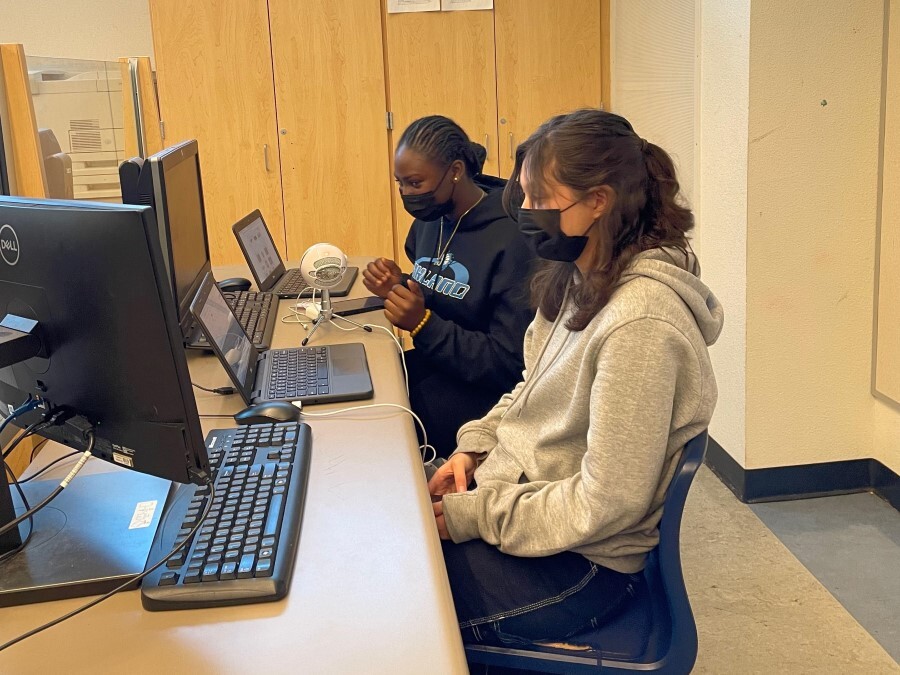

Students record and edit their Othering and Belonging podcast. Credit: Jessica Forbes

The Deep Pedagogy Sofrito of Strengths-Based Learning

My spouse, Jessica, had mentioned several times over the years in casual conversation that her time working in an upscale Californian/Italian restaurant in Oakland before she became a teacher had substantially influenced her approach to teaching. Jessica teaches high school English in a public health college and career pathway in an urban public high school in Oakland, California. Before that, she had worked both “front of house” as the host and volunteered “back of house” in the kitchen. But I didn’t get a clear sense of what she meant until recently. So one day I asked her to explain.

She said two things.

First, since she was the host, she learned how to read the energy and mood in the room, the flow of people in and out (seatings, how long parties took to eat their meals), the flow of wait staff back and forth to tables, the ways customers at different tables were feeling about their meals, the differences across different tables, the differing sounds of the space from table to table and over time, etc. Reading the room has helped with how she senses and manages a classroom dynamic each day (each day is different, each class is different, even with the same lesson design; each student is different, and different each day; each grouping of students is different).

Second, and maybe more pertinent to this conversation, is what she learned while working in the kitchen about the difference between Italian and French cooking (give me a bit of poetic license here). Generally, the French cook the food and then add the sauces at the end. The Italians layer from the bottom up; the bottom layer of ingredients creates the basic flavors of the recipe. For example, Italian sofrito is made with onions, carrots, and celery, which are chopped, salted, and then sautéed slowly in olive oil until soft. Later one might add tomatoes or tomato paste. The point of this approach (its purpose) is that when you cook bottom-up, the base flavors infuse the whole dish; if you don't salt the base right, you'll never get the balance; if your base is not cooked with attention and care, you will not be able to achieve the dish you envisioned.

Applying this lesson to the classroom means you build culture from the bottom up; you don’t pour it in at the last minute (or not at all). All the ingredients of SEL-informed practice; the science of learning and development; the brain-based research about identity, about feeling welcomed in and seen and feeling a sense of belonging; the trauma-informed practices that shift brain response to make it possible for students to learn at all; all the strategies to help kids ground, calm, and presence themselves; all the ways you help them connect, with themselves, with each other, with the teacher, with the content, with the world—these are the ingredients of the sofrito you start making at the beginning of the year and remake every day during class.

It’s the rituals and routines. It’s the foundation that makes learning possible and makes kids feel that they can take the risks to engage with challenging learning tasks, to engage in “productive struggle.” And this last point is maybe the most important. You aren’t doing these things just for the sake of doing them. They actually enable deeper learning, actively creating knowledge not just passively receiving information, the mastery and deep understanding of meaningful content, and the capacity to transfer learning authentically to broader contexts and purposes. They create the cultural and psychological conditions that support students to be able to experience the kind of learning that enables the results we really want to see. These practices might be called “deep pedagogy.”

So if we want to explore learning approaches that tap into strengths, gifts, interests, passions, and future goals of our students, this sofrito is what we want to construct in our classrooms at the beginning of the year, and every day again and again, over time. There is no magic way around it. As I said above, do it right or do it again. This is slow, deep learning. It requires slow, deep pedagogy.

Students receive feedback from a community partner. Credit: Alan Cash

An Example of the Deep Pedagogy of Strengths-Based Learning

And then I had the opportunity to see this process in action, and meet several students who had benefited from that kind of attention to deep pedagogy. Jessica and her colleague Tara, who teaches the tenth grade history class in the public health pathway, have spent the past five years developing and iterating a project-based learning (PBL) unit that is now called the Othering and Belonging Podcast unit (a shout out to john powell for that name). Students research and analyze examples of othering and responses to those that reconnect and recreate a sense of belonging with healing, as it were, from the effects of that othering. Examples include reforming neo-Nazis, reforming the police, healing from anti Asian American hate and other hate crimes, and resistance to the Uyghur genocide in China, among others. Students also study the genre of podcasts. They listen to and analyze examples of high-quality podcasts as “mentor texts” to anchor their sense of what high quality work sounds like. Next, in teams, they write a podcast script, gather sound clips and other materials, and then record their podcast.

Jessica and Tara build the sofrito, the ecosystem of a collaborative learning culture, each day (in fact, they have been building the sofrito all year in preparation for this unit). They use rituals and routines of belonging and engaging that help kids ground, calm, and presence themselves. They scaffold each aspect of the unit, conference with the students individually and in their teams to provide regular formative feedback, and support student teams to regularly provide peer critique of each other’s work. The point of the structure of the unit, this deliberate deep pedagogy, is that all students end up with a successful podcast and the authentic learning that is required to get to that end product.

Students then organize and MC a podcast exhibition of learning at the end of the unit, where they present their podcasts in a large public forum to adults from the Oakland community who have interest and/or expertise in othering and belonging and can provide feedback to the students about their effort. One major goal of the unit is for students to truly develop a sense of critical literacy in a way that it gets integrated into the student’s worldview and isn’t just a school task. Another goal is for it to result in some kind of action, to create an impact through developing student voice and the use of critical media in their podcasts.

Watch this 7-minute video about the unit (plus extended footage for those who want to learn more about the challenges, strategies, and recommendations for designing your own).

But equally important, and the reason I am emphasizing this podcast unit, is that unexpected students come out of the woodwork to demonstrate skills and strengths that the teachers didn’t even know about: recording skills, editing skills, speaking skills like poise and keeping a flow in a scripted conversation, and skills to draw reticent students out of their shells. The project has numerous entry points that allow students to shine, in particular because of the kind of multimedia critical literacy it develops. And multiple entry points and choice in the selection of their foci for the podcasts are key to all the students succeeding in the process and the product.

Two students I had the honor and privilege to interview about their podcast, Bryan and Alijah, put it this way:

Bryan: “[Our] podcast was about reforming neo-Nazis and tapping them back into society. Working with Alijah, like… We had a little bit of trouble, in the beginning, recording the podcast, and… in the end, we kinda got better. It was like a new experience for us…”

Question: Why did you focus on reforming neo-Nazis?

Bryan: “[it’s important for people]...to feel loved, and be supported by other people… I think it’s important to focus on this, to start leaving hate behind… Some people could be born with hate. It depends on what they are surrounded with, families, and what they see on the internet, being indoctrinated by propagandists.”

Alijah: “Like Bryan said, love and support in your community is like… I feel like treating everyone with mutual respect, that’s just basic, but like, I really appreciate my community for accepting me!

We chose this [topic] because we could really relate to it. You know, like, neo-Nazis, us being people of color [Alijah is Black and Bryan is Latino], because we could relate to it, we brought more attention to it. And people really liked that it sounded like a casual conversation, that it was a topic that we could just talk about. I really enjoyed making this project with Bryan, because it was just like a normal conversation between us. We was having too much fun recording this…”

Why do projects like this?

Bryan: “I think it is a good idea to do projects like this, because it’s very challenging, and it will get a lot of people thinking about new things. About what’s happening.”

Alijah: “Opportunities [to present work to other adults in the community] are super good for kids. Most people don’t even talk to [us] about what we want to do, so meeting people helps with meeting other people! So if you want to do something, that’s probably your ticket to do it!”

Assessing Strengths-Based Learning

All of this deep pedagogy and deep learning allows us to explore learning approaches that tap into strengths, gifts, interests, passions, and future goals of our students. All of our students. And that creates a sense of belonging in the classroom. And all of this raises the question of assessment: How do you measure belonging? Bryan and Alijah seem to have offered some answers for us. Look for the challenge, the joy, and the excitement in learners. The look of joy, the sound of joy, the messiness of joy, the chances to get better at something through sustained work on it. Tell the stories of those experiences. Back them up with the science of learning, and evidence of the pedagogy that enacts the science and results in the joy. Publicly create opportunities to connect students with other adults outside the classroom and thus allow them to show the quality of their work when the learning spaces make them feel a sense of belonging and well-being.

Othering and Belonging Podcast Exhibition of Learning. Credit: Alan Cash

Supporting Teachers of Strengths-Based Learning

And how do we support teachers to create and iteratively improve these kinds of deep pedagogy for deep learning? Give them the time to share these stories about practice with each other. Jessica and Tara emphatically point out that being able to collaborate makes this work. They have the time, barely, to reflect each week throughout the unit on how it’s going and fine tune their lessons along the way. They have the time at the end of the unit to reflect on how it went this year. They have the time in the fall to plan for the revisions they want to make. They also point out that the school’s pathway structure makes it possible to collaborate because they share all the same students. In addition, however, these two teachers also have to manage all the details of the student public exhibition of learning, which is almost another full time job.

So if we want this kind of learning for students, that involves an authentic public learning space for student products, we need to facilitate a public learning space for the teachers and provide the support and time for these additional tasks. That is, we need symmetrical experiences for teachers of belonging and well-being. Symmetrical experiences for teachers of joy and challenge in learning.

How? To reiterate, slow it all down, give people, both students and teachers, the time and space to do this authentic work, build the sofrito, be constructivist teachers, not consumerist teachers, and remember adrienne maree brown’s advice: “There is always enough time for the right work.”

Photo at top courtesy of Jessica Forbes.