Building Community

Structure Matters: How Network Form Affects Outcomes

Topics

When educators design and create new schools, and live next gen learning themselves, they take the lead in growing next gen learning across the nation. Other educators don’t simply follow and adopt; next gen learning depends on personal and community agency—the will to own the change, fueled by the desire to learn from and with others. Networks and policy play important roles in enabling grassroots approaches to change.

Create abundant value for education network participants by examining and shaping power dynamics, patterns of connections, and other aspects of network structure.

“As long as it remains invisible, it is guaranteed to remain insoluble.”

–Margaret Heffernan, Willful Blindness

In this post I will build on the ideas presented in two previous posts, Connection is Fundamental and Why Linking Matters. Let’s explore one way to leverage network effects and create abundant value for network participants: by becoming more aware of and tinkering with the structures of a network, or the patterns of connections and flows.

In a recent article sub-titled “How to Survive the Networked Age,” author Niall Ferguson briefly looks at the unfolding of the American and French Revolutions through a network lens and how this impacted their respective paths and outcomes. In the late eighteenth century, both revolutionary movements were inspired by the same ideas shared widely through a combination of publications, social gatherings, and written correspondence. However, Niall notes that the network structures of colonial America and that of ancien régime France were distinctly different, producing on the one hand a comparatively peaceful, decentralized democracy (though clearly benefitting some and not others and built on slavery), and on the other a more violent and occasionally anarchic republic that “moved on to tyranny and empire.”

According to Niall, what made the rapid evolution to French imperialism possible were in part industrial technologies, including railways and telegraphs, which supported the emergence of “superhubs.” These robustly connected cities were empowered by their centralized control of myriad communication and transportation routes; they exerted centralized economic and political influence over the surrounding countryside and relatively illiterate peasantries. This is an illustration of how the culminating influences of connection and flow may have a lot to say about the unfolding story of a social system and why it is important to be able to see and understand how networks work.

“As it is usually practiced, networking consists of going out and making a whole bunch of new connections, and then hoping that something good will come of them. It is much more productive to think about your position within the network as you create connections.”

–Tim Kastelle

“Think ‘Network Structure,’ Not ‘Networking’”

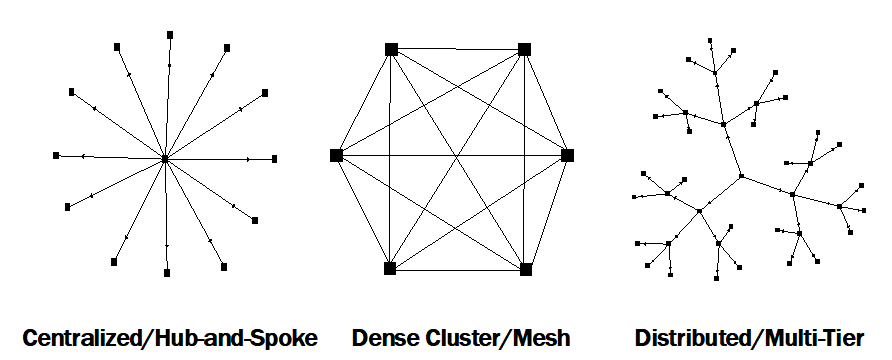

There are multiple forms that any network can take, and the form can impact what a network creates systemically for those involved. Focusing on and contrasting three perhaps overly simplified and distinct forms can help us to understand how structure matters:

- Centralized/hub-and-spoke

- Mesh/peer-to-peer

- Decentralized/multi-tiered

Centralized Networks

A centralized or hub-and-spoke network structure is dominated by a central node, or hub, that holds things together and through which most information and resources flow.

This structure can be a good way of harnessing otherwise disparate energy and providing coherent direction and a greater sense of shared identity. A hub-and-spoke form is what often results when a convening entity steps in to bring otherwise scattered actors together. And this kind of structure can also be or become a bottleneck.

Consider a network of schools that are convened and supported by a central organization. Over time, as the network grows and increasing demands are put on the central hub, the organization becomes hard-pressed to meet the needs of the growing membership. Those who were first served may feel more a part of the network than latecomers who must vie for strained attention. Furthermore, if member schools are not connecting directly with one another, they lose the value of peer-to-peer learning or partnerships. The entire network is relatively fragile—if the central hub goes away, so goes the glue.

Mesh Networks

A mesh or peer-to-peer network is a dense cluster (of people or organizations) in which participants connect directly and non-hierarchically to as many other nodes as possible and cooperate with one another. Often a community of practice takes this form.

Overall, the lack of dependency on one central node in such a network allows each node to participate fully in the exchange of information and other resources and to set the agenda. In her book Peer-to-Peer Leadership, Mila N. Baker highlights mesh networks for their promise and potential to dynamically self-organize and respond to changing demands and conditions.

The ability to take such initiative in peer-to-peer arrangements enables a more sustainable distribution of workloads, particularly in the event that a few nodes should disappear. Peer-to-peer networks are characterized by what Baker calls “equipotency” (instead of fixed positional authority) and “relational dynamics” (instead of purely role-based and transactional arrangements)—think of high functioning trust-bound teams (of students, teachers, other professionals) that share work and regularly rotate roles.

One potential downside of this kind of network structure is that it can become fairly insular without much reach beyond itself. A lack of openness can be its downfall in the long run if it is not open to new energy and ideas to keep it dynamic and relevant.

Decentralized Networks

A more distributed form, or decentralized/multi-hub network, can be especially useful for mobilizing large numbers of actors and diffusing information more widely.

This form of network sometimes results from development through and/or integration of hub-and-spoke and mesh forms, where there are multiple clusters of hubs with connections that are connected to one another. This is not to say that evolution is guaranteed, linear, or even desired. Certain national education networks and networks of networks can take this form.

The weakness of more decentralized forms of networks is that they are generally less effective at defending themselves, if that is a need, than more centralized or centrally coordinated forms. Again, one network form is not necessary inherently better than another, rather it depends upon context, goal(s), desired value creation, etc.

So an important consideration for network builders is: What is the overall pattern of connections and flows in your network?

Equity and Power in Network Structures

Networks are not necessarily easy to control in terms of their overall structure, especially when they are large and complex (diverse and widely distributed). And it is important to note that there are network phenomena that may tend to pull a networked endeavor in a certain structural direction.

For example, homophily is a phenomenon where social networks tend to form clusters of nodes with similar properties or attributes. This is captured by the adages, “Birds of a feather flock together,” and “Those close by form tight ties.” The result can be self-segregation along various lines of difference, for example racial, cultural, or class divisions in schools. Or consider the current pronounced political polarization in our country. The key to confronting homophily is to be both aware of the tendency and diligent about creating structures and incentives for bridging across boundaries.

“Opportunity … depends, at least in part, on our inherited networks.”

–Julia Freeland Fisher

“Disrupting Opportunity Gaps Will Hinge on Networks”

One of the great hopes and marvels of networks is that they can be liberating, especially in the face of bureaucracy and various barriers (see more about “network effects” in the previous post in this series). While this is worthy of celebration, another important phenomenon to be aware of is that networks can be deeply inequitable.

For example, sociological research shows how larger networks can be marked by larger hubs with disproportionate influence, which contributes to a familiar dynamic of the rich getting richer. In addition, there is evidence that inequities, if unchecked, can accelerate, especially in the digital age. In a recent report entitled “Power-Curve Society,” Kim Taipale of the Stilwell Center for Advanced Studies observes, perhaps somewhat provocatively given the apparent trajectory of our increasingly hyper-connected economy and society: “The more freedom there is in a system, the more unequal the outcomes become.”

Especially given the current pace of change and disruption, there is a more recognized need to mitigate some of the widening structural divides in organizations and society with cultural and political/policy interventions.

“What is needed is culture, shared knowledge and education to allow systems to metabolize change and to efficiently manage the out-of-control phases that accompany the accelerations imposed by technology, which – it must not be forgotten – is always a product of culture and never something ‘external.’”

–Piero Dominici, “Rethinking Education … Beyond the ‘False Dichotomies’”

So another important feature of attending to network structure is looking at power dynamics and inequities, and how these can be reinforced in detrimental ways.

A few questions for you to consider:

- To the extent that networks are creating value in your work, who is creating and getting that value? Who is not?

- How are the patterns and nature of connection and flow in your network and/or networked activities addressing inequities of opportunity and outcome? How might they be exacerbating them?

- What might be done intentionally to ensure that there are more equitable opportunities and benefits?

Next Generation Learning Challenges invites you to respond to these ideas about network effects in education and learning. Please comment below and join the conversation in the NGLC Networks for Learning group on LinkedIn. The group asks how we design our networks, how we act within and across them, what we know works well, and how they can best drive future learning shifts in K-12 education.

Photos, from top: Thrive Public Schools; Montessori for All; used with permission.