New Designs for School

Student Work Showcasing Portrait of a Graduate Competencies

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

These examples of student work that develop and demonstrate graduate portrait skills come from NGLC’s Portrait of a Graduate in Practice stories. See what students do when schools move from portrait to practice.

It’s easy to understand why Portraits of a Graduate and Graduate Profiles and Learner Portraits are gaining in popularity. For one, there’s the visually striking posters and inspiring descriptors—they express a unique personality for their schools. Also, graduate portraits can bring communities together by expressing what the community agrees is most important for their youth. And above all, they set a higher shared purpose for the very hard job of learning and teaching in our schools.

That’s why it’s easy to understand why these portraits are popping up all over the country. But it’s another thing entirely for school communities to figure out what to do next.

In the past the skills found in many graduate portraits—Lifelong Learner, Innovative Problem Solver, Leadership, Empowered Citizen, Self-Directed & Resilient Individual—were rarely emphasized in the curriculum. They were often left to chance, or “teachable moments,” or after-school activities.

No doubt, many teachers took it upon themselves to make sure students in the courses they taught developed some of these skills. But when a community says these skills are The Most Important Things... and when the research and future employers agree these skills are The Most Important Things… then that leave-it-to-chance approach is no longer an option.

So what does it look like when students are engaged in learning that’s specifically and intentionally designed to help them develop the competencies in a graduate portrait?

Lucky for us, the five sites featured in NGLC’s The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice have shared many examples of actual work completed by learners in their schools. The kind of work that helps students develop, and demonstrate, graduate portrait skills. The kind of work that leads to The Most Important Things. Let’s see what it looks like!

Examples of Student Work that Develops and Demonstrates Graduate Portrait Skills

Fountain Project, Bullitt County Public Schools

In one of the Portrait of a Graduate in Practice short podcasts, Bullitt County Public Schools (BCPS) high school student Lexi Morton describes a collaborative learning experience in her algebra class that integrated academic content with Graduate Profile competencies. Lexi and her classmates created a fountain for an amusement park—calculating the sprays and applying domain, range, and quadratic equations to do so. In an impressive extension of the project, the students also designed the rubric that was used to evaluate their work.

Lexi’s teacher, Kim Ludwig, offers more context in the same podcast about integrating the practical Graduate Profile competencies with the abstract concepts in algebra. And when you read the BCPS story in The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice series, you’ll find that Kim further explains what she did to change her instructional practices so her courses are more learner-centered—the challenges and frustrations as well as the rewards that have come from teaching differently and seeing kids “blow her away” with their learning.

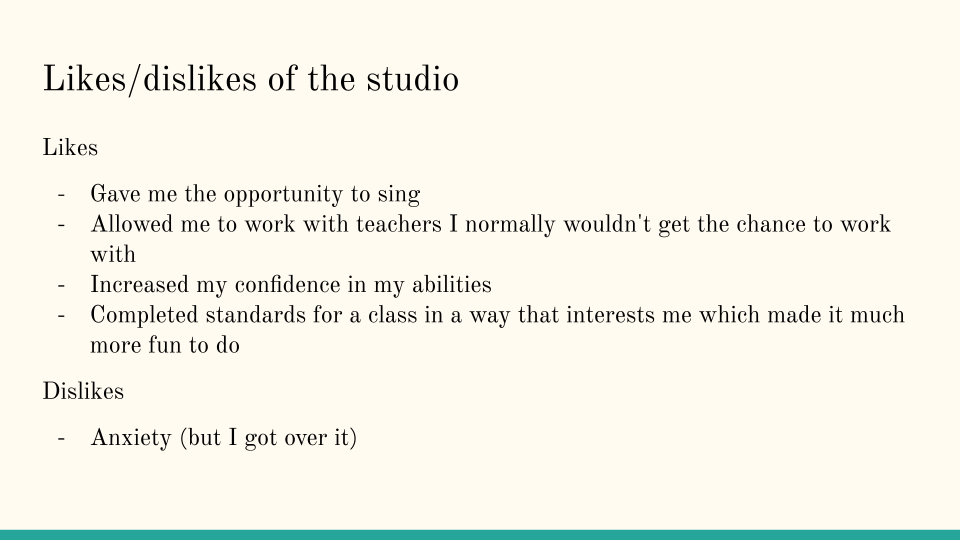

Film Studies Studio, Northern Cass School District

In a studio course, Northern Cass School District (NCSD) senior Emily K. created a new version of the final scene in the film Into the Wild, updated with an alternative song that she performed and professionally recorded. The NCSD Portrait of a Graduate in Practice story links to Emily K.’s final work product, which includes a video featuring her song as well as her reflections on the experience. Through the studio, this learner received coaching support to manage the independent project and worked with an external partner—a professional musician who has a recording studio. In the NCSD story in The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice, the district’s director of personalized learning Tom Klapp describes how studios are co-designed with learners by starting first with engagement, relevance, and Portrait of a Learner skills, and then after that, they build in the required content standards.

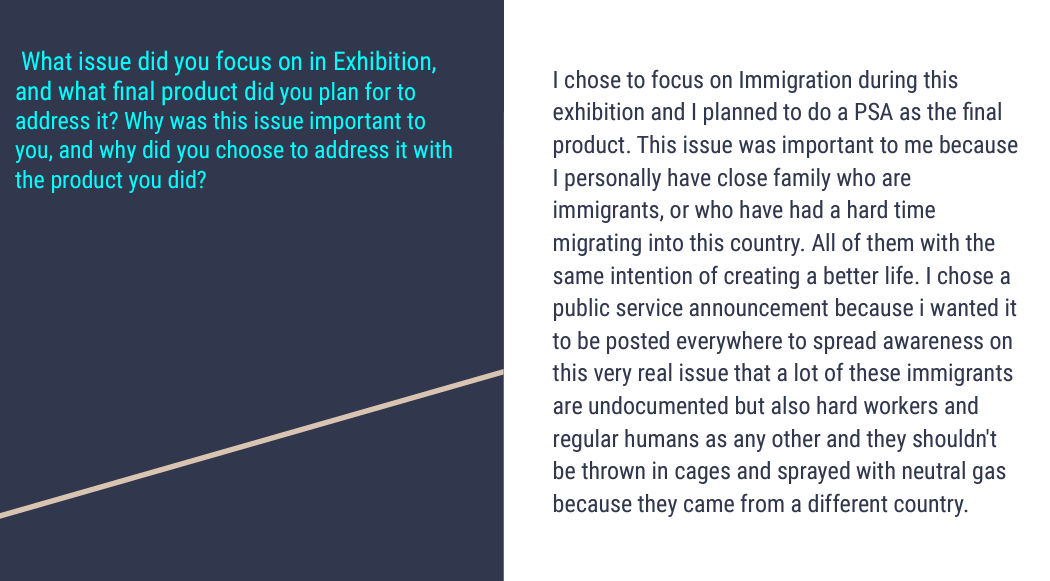

Exhibition Reflections, Da Vinci RISE High

The Da Vinci Schools Portrait of a Graduate in Practice story includes one RISE High School learner’s slide presentation which contains their reflections as well as evidence of their learning. The learner created this slide presentation as part of an exhibition. Public exhibitions and presentations of learning are a signature practice of all Da Vinci Schools. At RISE High, an innovative alternative high school for at-promise youth, exhibitions help learners connect the day-to-day actions within their courses with the big picture and vision of the school. The RISE High Graduate Profile encapsulates that big picture and vision, states the school’s executive director Erin Whelan, which you can learn more about in the Da Vinci story in The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice.

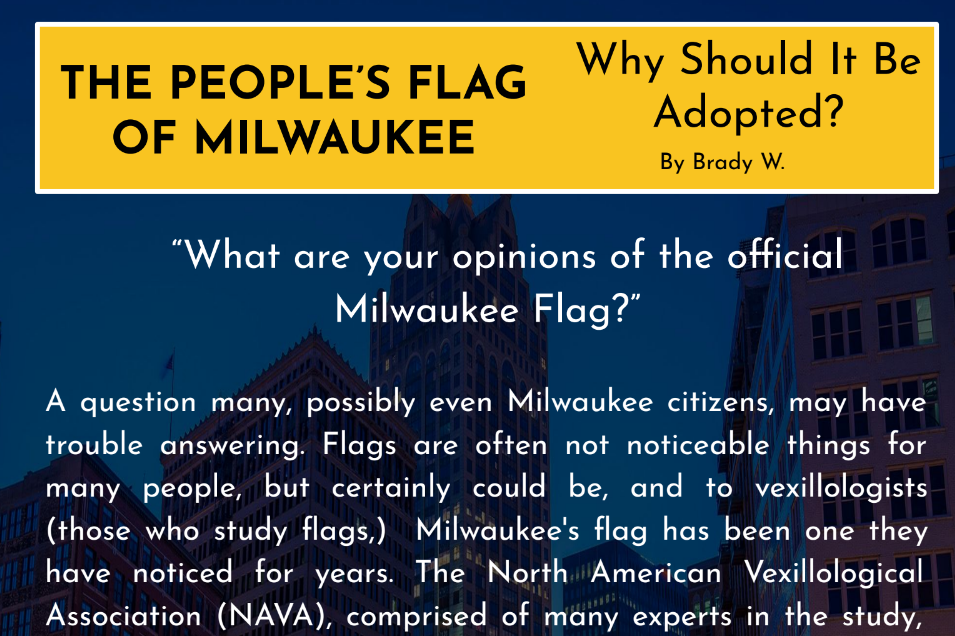

Inquiry Projects, KM Global High School

“The People’s Flag of Milwaukee” is a magazine article written by Brady W., a learner in KM Global High School in Wisconsin’s Kettle Moraine School District. Brady created this work product through their semester-long inquiry project. Inquiry projects at KM Global support both academic learning and development of Graduate Profile components like Engaged Citizen. Two more KM Global learners, Maddie B. and Jacob H., describe their inquiry projects in an 8-minute Portrait of a Graduate in Practice podcast. The Kettle Moraine story in The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice series offers more details about this interdisciplinary learning experience for all KM Global students.

Senior Exit Presentations, Lindsay Unified School District (LUSD)

During this senior exhibition at California’s LUSD, learners present what they learned and how they have grown during their time in the district to a panel of community members, teachers, school board members, and others. In the LUSD story in The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice, Lindsay High School principal Cindy Alonzo describes how learners demonstrate the district’s Lifelong Learning Standards (LUSD’s version of graduate portrait skills) as they present. A copy of the presentation outline and rubric is also available in the story.

Features of Student Work that Develops and Demonstrates Graduate Portrait Skills

What common threads do you see in these examples of student work? Here are a few commonalities that I noticed:

Real-World Connections

Real-world connections provide relevance and purpose to student learning. In the Da Vinci Exhibitions and LUSD Senior Exit presentations, learners present their work to authentic audiences. NCSD’s Emily K. worked with a local musician, in a recording studio that professional artists use. The BCPS fountain project is grounded in a real-world design challenge. KM Global’s Brady W., Maddie B., and Jacob H. all completed authentic work in their inquiry projects. These real-world connections elevate the learning experience, give purpose to the effort students are asked to put in, and help learners develop skills that can be used in any setting, inside or outside of classrooms.

Engaging Students with Agency, Voice, and Choice

In these examples, learners did most of the work of learning and developing and demonstrating the skills themselves. They were leading their learning, not their teachers.

For example, BCPS algebra students created the rubric that would assess their fountain project designs. Their teacher Kim Ludwig reported that the students expected more to receive the top score on the rubric scale than she might have set herself. Talk about rigor and high expectations! She also described what it meant for her when students were more engaged in their learning during this project: “With the old way of doing it, it’s me for 55 minutes—standing up there delivering the instruction, doing the notes, going through the problems for the whole time. Now I’m stepping back to let them lead the show, and I’m not so exhausted because I’m not the one delivering the instruction five periods a day, 55 minutes each period.”

The projects and presentations that led to the work products above are filled with opportunities for learners to make decisions—what they will learn, how they will learn, how they will demonstrate their learning. Teachers set parameters, guide the process, and provide instruction and support as needed, but the learners are the ones who are most actively engaged in their learning.

Reflection

Most of these work products are accompanied by some kind of reflection. The ability to consider the experience, weigh the evidence, and determine next steps that will help them continue to grow—these seem essential to developing the kinds of skills found in graduate portraits. Take the reflection response on the Da Vinci RISE learner’s exhibition slide presented above for an example. This simple reflection sheds light not only on the personal connection the learner had to their project but also the decision-making process they used during the project. The reflection adds depth and rigor to the learning experience; it requires self-awareness and critical thinking.

NCSD student Emily K.’s reworked final scene of Into the Wild is impressive in and of itself. I can see Accountability, Communication, Adaptability, Learner’s Mindset, and Leadership—all five of the Northern Cass Portrait of a Learner skills—in the final product. But to me, the most telling is her reflection of dislikes about the experience: “Anxiety (but I got over it).” In six words, she conveyed the challenge of the project, the support she received to persevere, and the integration of academic, social-emotional, and 21st-century skills that she relied on to succeed. Just think of all that Emily K. is able to take on and do now!

All Students

The work the five sites shared in their stories is work that all students in their schools do. Some of these examples, like the fountain project and the film studies studio, came from pilot learning experiences that a small number of students participated in this school year, but the schools are working to build out these opportunities across subject areas, grade levels, and courses. But the point is that these examples of student work are not “the best of the best.” They don’t represent work that only a few students get to do. They represent work done by any and all students in their schools. I think this may be the greatest power that activating a graduate portrait can provide a school community—providing equitable access to learning experiences that lead to The Most Important Things their learners need to succeed. No more leaving it to chance; these teachable moments are baked in.

The Teaching and the Conditions Supporting Student Work that Develops and Demonstrates Graduate Portrait Skills

Learn more about the work underway in the five Portrait of a Graduate in Practice sites as they develop new learning designs focused on a broader, deeper vision for student success. Read the stories and listen to the podcasts to explore how each site developed their graduate portrait, how teachers are reimagining learning in their courses, and how schools are supporting teachers and students through professional learning, operating norms, and school culture.

And then watch the recording of the Bravely Activating Your Portrait of a Graduate workshop that provided participants best practices, resources, and tools you can use to help you take the next step in your own #PortraitToPractice journey.

Photo at top courtesy of Lindsay Unified School District. All other images belong to the students that created them.