New Designs for School

Students Win When Teachers Try a “Move When Ready” Learning Approach

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Teachers can make the shift to competency-based education and multiple pathways for learning with strong leadership, empowered teachers, and collaborative teaching practices.

Whenever I have conversations with teachers or school leaders about competency-based education, we get excited about greater educational equity, more opportunities for student agency, and authentic means of demonstrating what they know and can do. It’s all positive…until we start talking about multiple pathways and a move-when-ready structure to support those pathways—particularly at the elementary level. We agree in theory that students shouldn’t have just one pathway available to them and they shouldn’t move along their learning journey based on arbitrary calendar dates. This industrial model of education doesn’t work for us anymore. We’re interested in producing 21st-century thinkers, innovators, and engaged global citizens, not robotic factory workers. But envisioning the structural change needed to truly enact this component of a competency-based system seems too overwhelming. How do we redesign grade levels, classrooms, school buildings, and calendars—is this even possible?!

I am convinced that with the support of strong administrative and teacher leadership, we can begin to move the needle on creating multiple pathways for students and allowing them to progress as they demonstrate mastery. Change to our educational system won’t happen overnight, but as is often the case, change begins with an empowered group of people who are passionate to try something different.

How do we redesign grade levels, classrooms, school buildings, and calendars—is this even possible?!

I recently visited a collaborative team within a professional learning community (PLC) at Woodman Park School in Dover, New Hampshire. The team was reflecting on their end of year S.M.A.R.T. goal and sharing their experiences about differentiating reading instruction by using a “What I Need” (WIN) block. The team was remembering their fall data which indicated that only 56 percent of their Kindergarten students were reaching benchmark-level achievement in reading development.

At that time, they were tempted to set their end of year proficiency goal at a conservative 75 percent, feeling even that was perhaps a too-aggressive goal. Their students had lived their young lives in the midst of the pandemic and most had not attended a consistent preschool to gain the prerequisite skills they usually had. But an administrative leader challenged them to think deeply about what they wanted for their students. After this reflection, they took the leap and set their end of year goal for 80 percent proficiency—what they’d expect for their students at the end of a “typical” year, though of course these years are anything but.

These teachers spent the year sharing students and providing them timely, differentiated support based on their needs. While reluctant at first to share students, again with administrative support they experimented with a structure where students traveled to a different teacher and met in a small group to receive targeted instruction. These teachers drew on each other’s expertise, they trusted each other, and students benefited greatly.

One member of the team noted about a struggling student in her class, “I can’t give him what he needs on my own,” so during the WIN block he worked with another teacher on the team who was trained in a research-based reading intervention approach called Orton Gillingham. By sharing this student across the team, he was able to get the trained intervention support he needed.

Reflecting on a student who came in with very low proficiency, another teacher shared, “I’ve never been able to move a student like that by myself.”

Yet another teacher noted that there were two students whom she ordinarily would have referred to special education because their proficiency was so low, but because of the structure of their team support, these students made the progress they needed to, recovering academic gaps, and she was no longer as concerned about them. “That’s never happened in the past,” she noted.

This is what collective teacher efficacy looks like—these teachers interdependently made decisions, took risks, leaned into their own expertise, responded in a timely way to student need, and enacted change. As a result, they not only met but exceeded their 80 percent end of year proficiency goal—in fact 86 percent of their students met proficiency at the end of the year! These students have administrative and teacher leadership to thank for their gains.

This group of teachers and the administrators who empowered them did not make structural changes to the school district or even their school building. They didn’t change the school calendar, rearrange the entire schedule, or get rid of grade levels. What they did do was powerful though. They enacted a change that was just right—for them, and ultimately for their students. They have created a foundation that can be built on and expanded.

This is how we begin to realize a multiple pathway, move-when-ready model in our schools—administrators support teachers to collaborate interdependently and empower teachers to take risks and make evidence-based decisions. As Ernest Hemingway famously said, change happens “gradually, then suddenly.” The same can be said for our educational systems when teacher leaders own the work.

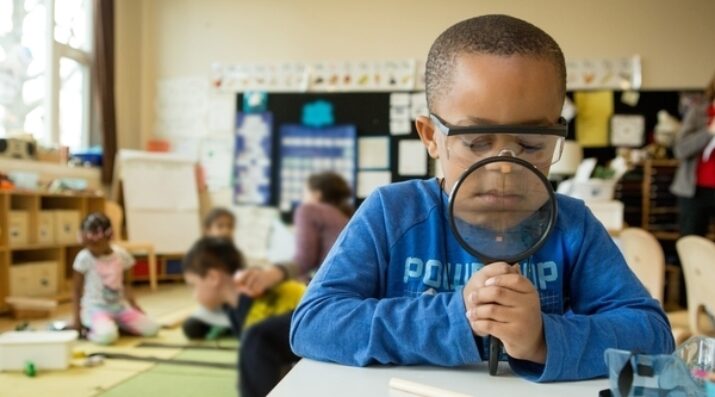

Photo at top by Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages.