Teaching Portrait of a Graduate Skills

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

What is it like for teachers when their school district adopts a Portrait of a Graduate?

Find out how teachers are changing their role, mindset, and instructional practices to help their students develop graduate portrait skills.

Meet Zak Lenski, Nancy Wills, Beth Head, Luke Bush, Tom Klapp, Mackenzie Tadych, Michelle Rainey, Erin Whalen, and Kim Ludwig.

In NGLC’s The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice, these nine educators were among the 50 people who generously shared their experience working in school systems that have a graduate portrait.

These educators describe what they are doing to make sure that all students have high-quality learning experiences that help them develop the competencies in their portrait. They explain how they are rethinking the purpose of school and learning. They detail how they are changing their instructional practices. And they share how the roles of both teachers and students are evolving.

Guiding Personalized Learning Plans and Designing a Real-World Learning Project

Zak Lenski, Social Studies Teacher and Learning Coach, KM Global

Zak Lenski is a social studies educator at KM Global, a charter high school in Kettle Moraine School District (KMSD) west of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Zak says the KMSD Graduate Profile has helped him focus his lessons on what’s most important. “Whether it’s academic or personal, it’s less about the content driving us and more about how this content gets you closer to that model student,” he says. “And by the time they leave here, the students have become a more adult version of themselves.”

KMSD sees the rich opportunity that real-world learning offers students to develop Graduate Profile skills and mindsets. Zak, for example, created a mock trial project:

“I love law. There are great skills students can learn while exploring our judicial system. So I reached out to the state bar of Iowa and they had a middle school case I thought was pretty interesting. Now students have a six-week crash course during one of our seminar offerings. They learn about the court proceedings and affidavits, direct examination, cross examination, opening and closing statements. They learn about the judicial code of conduct. In week six we do a mock trial case, with students acting as lawyers and witnesses. We’ve gone to Marquette Law School to use their practice trial court. Getting into a courtroom dressed for the part makes it a bit more real life.”

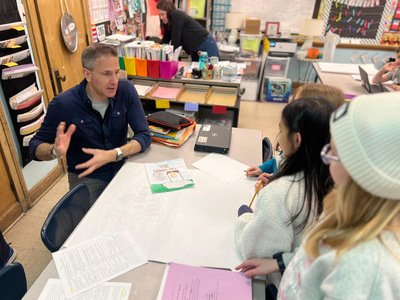

Credit: Kettle Moraine School District

Zak is also a learning coach, a new role at KM Global that grew out of the broader goals for learning that are defined in the district’s graduate profile. Each KM Global student plans their high school experience with the help of a learning coach and the Personalized Learning Plan (PLP). “We go into that personalized learning plan, and we actually plan out year by year,” Zak explains. “It’s not just picking classes, but it’s a great way for me to have conversations with kids about how they’re thinking about their planning and to be purposeful, not flippant, with decisions.” As a learning coach, Zak also supports and mentors learners working on their semester-long inquiry projects. “Within that inquiry process, the Graduate Profile shines the most because students select a topic that is near and dear to them or something that they’re interested in, having a bit of that voice and choice and being more self-directed in what they’re going to be looking at.” During this deeper learning experience, Zak meets with learners to assist in project development, provide individual support, and monitor learners’ progress toward their goals.

Embracing Learner Agency in Curriculum and Grading Practices

Nancy Wills, Chair of the Visual and Performing Arts Department, Lindsay High School

In Nancy Wills’ music classes, learners have to have the skills expressed in Lindsay Unified School District’s (LUSD’s) Lifelong Learning Standards (the Central Valley California district’s version of graduate portrait skills). “If you don’t have good practice habits, if you don’t have grit, if you don’t have self-determination, there’s really no way to be successful” in her class, Nancy explains. The lifelong learning standards “were something I really wanted to incorporate into what I do in the classroom in order to produce a better product.”

But when she struggled to engage learners during the pandemic, Nancy began to evolve her teaching to embrace learner agency. Her first move was providing choice. “Rather than only using traditional music reading, I also incorporated YouTube tutorials, different types of resources, and different types of learning. Things that are available and used by professional musicians.” Then she jumped into transforming her curriculum and grading in order to place learners’ goals and growth at the forefront.

Nancy offers an honest reflection when she says that the changes have been “really terrifying, but also super rewarding. What was so terrifying was that I’ve had a very successful, high-quality program, but only 40 percent of those kids were really excelling. The others were just kind of hanging on. Now it’s a little more out of control because I have 200 kids. They’re all learning different things, but they’re learning the things that they want to, what they’re passionate about. Kids are so excited to come to class now.”

The result, Nancy says, is that learners are not only more interested to learn but also, “This is where the lifelong learning comes into play quite a bit. They’re trying much harder. They’re willing to keep going.”

Taking on New Roles and Designing New Courses

Beth Head, Science Teacher, Northern Cass High School, and Colleagues

Serving six rural communities northwest of Fargo, North Dakota, Northern Cass School District believes that sharing ownership of learning with students is one significant way to help them develop skills in the district’s Portrait of a Learner. Science teacher Beth Head describes her role in self-directed learning in ways that reflect the “guide on the side” approach. “My role is that I probably answer a thousand questions a day,” she begins to explain. “If you walked into my room, I would most often be sitting next to an individual learner or a small group and answering questions versus standing in front of the room.”

Beth continues as a guide-on-the-side even with assessment:

“It’s really about transparency, getting the proficiency scales in kids’ hands and interacting with them so that they know what’s being assessed from the start. As my kids are working through, say, a physics concept, the keys are all available,” she explains. “They’re checking their own work, they’re scoring themselves. I’m there to clarify, maybe re-explain something in a different way. So my role is more of giving feedback: ‘Okay, we got this one wrong. Let’s figure out where we went off.’ It allows me to sit down with that kid and work with them immediately.”

Beth’s colleagues, Luke Bush, Tom Klapp, and Mackenzie Tadych, are also rethinking their teaching practice. In the 8-minute podcast embedded below, Luke describes how he teaches middle schoolers Portrait of a Learner skills in gateway classes. To provide learners with the relevance they crave, Mackenzie says, her role has grown to include working with industry and community partners to engage learners in hands-on projects, internships, job shadowing, and other experiences. And Tom explains that in their pilot of a studio course, he works with learners to design their own passion projects by starting with Portrait of a Learner skills and then working backward to incorporate content standards.

Tom summarizes his mindset about the innovative work going on at Northern Cass when saying, “You’ve got to try. We’re always trying new activities and new methods. That’s how we grow our practice and become great at what we do.”

Responsive Teaching and Supporting the Whole Child

Michelle Rainey, Executive Director, Da Vinci Connect

Michelle Rainey is an English teacher turned principal and is now executive director of Da Vinci (DV) Connect, one school in the Da Vinci Schools network serving learners in greater Los Angeles. She says that being a lifelong learner is par for the course for Da Vinci educators: “We are constantly surveying the landscape of what is expected of these learners when they graduate high school, when they graduate college, and when they enter the workforce. We think about how we can be continually responsive to that in our program.”

For example, Michelle and her DV Connect colleagues “revised our Habits of Heart and Mind [what other schools might consider a graduate portrait] annually until we got them right. And we know they still may change again.” Being this responsive is valuable for students, and it makes for an exciting and energizing environment to teach in, but Michelle is clear that it can also be a challenge.

Michelle says that their willingness to examine practice and revise is “one of my favorite things about Da Vinci [but] also one of the hardest things” because it creates ambiguity. “I understand and empathize with that,” Michelle continues. “But it’s not how humans work, and it’s not the world we’re preparing our kids for” and that’s why it’s necessary.

And that’s why DV educators work to balance responsiveness with stability for students, families, and themselves. For students and families, Michelle says DV Connect teachers, counselors, and school leaders make themselves available, approachable, and accessible:

“Traditional systems are created to keep people away from the people who make the decisions. We do the opposite. My office was always right in the main corridor, door always open…. Same thing with our counselors. We hope that these intentional decisions result in students and families feeling comfortable sharing feedback…. It makes authentic communication and feedback constantly happen.”

Credit: Da Vinci Schools

For teachers, the work becomes more sustainable because teachers have flexibility in their instructional practice. Take all the different ways teachers might support students with the Accountability aspect of the Habits of Heart and Mind. “Some of our teachers believe very much in rubrics,” Michelle says, “and some want quality indicator checklists. There isn’t actually one right or wrong way to do that, so we give flexibility as long as they are guiding students.”

Erin Whalen, Executive Director, Da Vinci RISE

Michelle’s colleague, Erin Whalen, is the executive director of another Da Vinci school, DV RISE High School. For Erin, the DV RISE Graduate Profile changes the teacher experience because it is a definition of student success that recognizes learners as whole persons. And that can be uncomfortable. “For a long time,” he explains, “learning was so based on the Carnegie unit, on rote memorization, that many people have anxiety around moving away from that.”

One change to RISE teachers’ roles is working outside of their discipline. Teachers work with colleagues in different content areas to support interdisciplinary learning and they work closely with the school’s mental health team. The cross-training between teachers and mental health practitioners is intentional, Erin says, “so that there is a continuity of understanding of the two worlds that impact our kids.” RISE was designed to serve youth experiencing homelessness, foster care, housing instability, the juvenile justice system, and populations considered transient. Erin goes on to explain, “What I find is teachers often burn out when they see a kid struggling with very real life circumstances and have no materials and no way to help.”

So RISE educators know about probation and foster care and other issues that RISE students are dealing with. “We give our teachers space to learn about these worlds,” Erin explains, “but also have professionals in the building to help kids navigate them. It’s like, ‘I need to understand the social services agencies and the different organizations that are impacting our kids. I’m still a teacher. It’s not my sole job to learn them, but I know about them. I know my tools.’”

Integrating Content Knowledge and Graduate Profile Skills

Kim Ludwig, Math Teacher, Bullitt Central High School

As a high school math teacher in north central Kentucky’s Bullitt County Public Schools (BCPS), Kim Ludwig says her teaching style before the district adopted its graduate profile was “old-school” and “very structured.” Kim admits that she didn’t see a reason to change her approach. At first, she didn’t even buy into the Graduate Profile. She was invited to join the team of district and community members leading the creation of the BCPS Graduate Profile, and at her first meeting, she remembers thinking, “This all sounds great, and it’s going to be the next new thing that comes along, and it’s going to be gone in a year or two.” But a new idea presented at the meeting changed everything for Kim:

“Suddenly I was like, ‘The world changes so fast that I’m preparing kids to go out into a world that doesn’t exist yet. They’re going to be doing things that aren’t there yet.’ I put down my phone, and I closed my computer, and from that point forward they had me. That was my hook.”

Once open to the potential that the district's Graduate Profile offers, Kim became more open to re-examine her practice. “When the Graduate Profile came out, it really got me to think about what I could do differently,” Kim explains. “I had to think, ‘Okay, if I’m a kid who doesn’t like school, how much do I want to come to school if every single one of my classes is just come in, do the bell ringer, take out my notebook, take notes, do an assignment, do an exit slip, leave, go to the next class, and do it all over again?”

Kim has since focused on two significant changes to her instruction. First, she is incorporating projects in which learners apply math concepts and develop Graduate Profile skills together. Listen to Kim and one of her students talk about the fountain project in her algebra course where students are developing their knowledge and skills at the same time.

Second, she is taking a more learner-centered approach, exploring ways to “take a step back and let [students] have some control on a daily basis.” She found strategies for students to talk more (and for her to talk less), to present, and to be more involved in what and how they learn. For example, students created the rubric for that fountain project. Kim was skeptical, but ended up delighted. “The conversations that they had coming up with this rubric were far better than anything I would’ve gotten on any paper-pencil test,” she says. “They all deserved an A on that unit. They were using the vocabulary correctly. They were using the content material correctly. They were harder on themselves than I would’ve been on them.”

Credit: Bullitt County Public Schools

Kim says that these changes take time and require persistence and practice. It’s probably not going to be perfect the first few times, Kim advises, because the teacher and the students need to get out of their old habits and form new ones. Kim has also noticed that teaching in a learner-centered way requires more preparation. But, she says, “I’m working far less hard in the 55 minutes that they’re in my room than I was before…. Now I’m stepping back to let them lead the show, and I’m not so exhausted because I’m not the one delivering the instruction five periods a day, 55 minutes each period.”

Support for Teaching the Graduate Portrait

The experiences of these innovative educators offer so much insight into what happens after a community adopts a portrait of a graduate. However, in The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice, we learned about the professional learning and school culture that made their innovative changes possible. We learned about the organizational conditions that made it possible for these teachers to provide what their learners need most.

Professional Learning

- Teacher agency and autonomy. When asked how DV Connect educators are supported to innovate and design the learning experience, Michelle replied that “it starts with having the autonomy and the agency to say, ‘We want to change this.’” These school systems in The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice have seen that the adult experience is a mirror of the student experience, and they describe professional learning for teachers that have the same kind of attributes as their graduate portraits. A personalized, learner-centered approach to professional learning at KMSD, says Andi Kornowski, director of KM Global High School, “is what truly leads to what happens in the classroom. If we didn’t have that autonomy in our professional learning and we weren’t able to explore the things that we were passionate about, I don’t think that that would lead to the great learning experiences that we currently have in the classroom.” The same is true of the graduate profile professional learning cohorts in BCPS. “It’s a professional learning system that gives teachers voice and choice,” says assistant superintendent Adrienne Usher, “like we should give our kids. As a district leader, I don’t believe in getting up and saying, ‘By 2025 we’re going to have 45 percent of our classrooms doing a PBL [project] or a [portfolio] defense. That would be forced and about compliance. It wouldn’t be authentic.”

- Instructional coaching. We heard directly from several instructional coaches, like Beau Kaelin in BCPS, Joel Martinez Dominguez in LUSD, and Jill Gilbert in KMSD, about how they work with teachers to incorporate graduate profile skills and mindsets into course content. The added value of a coaching model is that coaches develop a collective perspective on teaching and learning shifts that are happening across a school. “We realized that we’ve got these pockets of great things happening all across the building, and we have incredible teachers,” explains Jill. “Instructional coaching has really allowed us to scale and leverage the strengths of the people in the building. I see my role as knowing what’s happening in all the different parts of the school and making connections and opportunities for collaboration.” In this way, instructional coaching is a strengths-based support that encourages a growth mindset.

- Peer-to-peer learning and partnership. This work is difficult, but the districts and their teachers are not alone. The districts provide teachers with the opportunity to connect with colleagues within their school, across their district, and beyond. Teachers are improving their practice by working together. Cinnamon Scheufele, the executive director for curriculum and instruction at LUSD, says it best when she explains that “teaching in a silo with your door shut is not a thing here anymore, but it used to be. Fifteen years ago a new teacher might hear, ‘Well, good luck’ and hope it works out. We were not collaborating. No, we tried to do it all by ourselves. And I think we were mostly terrified that anyone would see us teach, even if we were really good. And now routinely you turn around and there’s six people in the room because it’s more of a lab school environment. Teaching in isolation doesn’t really benefit the learner or, in my opinion, the adult either.”

Culture of Innovation

- Safe to “fail.” In a sector steeped in capital “A” Accountability, rife with capital “C” Consequences, these districts have been relentless about creating a new culture that supports teachers to try new things and encourages adults to learn and grow professionally. For example, BCPS superintendent Jesse Bacon describes the messaging, modeling, and active interference he provides to build this culture as he explains, “we do not expect them to be perfect, but we do expect them to show growth, and also tell us where we can help them along the way.”

- Continuous learning. A culture of continuous learning means that district communities seek out new information, like the latest research in learning science and workforce trends, and take stock of our changing world (COVID and ChatGPT, for starters!). As Mackenzie explains of NCSD, “It doesn’t matter if we’re learners in elementary school or high school educators, it’s an expectation and a mindset that everyone is always growing. Everyone might be running at a different speed, but we’re all going forward together. That’s the mindset of the school.” And the director of the Da Vinci Institute, Megan Martin, recommends getting outside of your own school environment, to “visit inspirational hubs—schools and places and programs that are doing innovative work—and keep talking to a lot of other educators.”

- Community-focused and learner-centered. These school systems are breaking down the hierarchy of district bureaucracy, inviting and welcoming the voices of learners, families, community partners, and teachers into decisions—whether it’s a community-engaged process of defining success through their graduate portrait or teachers and learners co-designing learning experiences. Paired with this community-based design approach is a distinct shift away from a teacher-centered to a learner-centered environment. As Cinnamon at LUSD explains, “You can have the best lesson you’ve ever taught, and—I almost hate to say it—if the learners are not really learning, it almost doesn’t matter.” And her colleague Yazmin Martin Aceves, coordinator of the district’s teacher residency program, further explains that “a learner-centered environment is really about giving up some ownership and co-creating a learning environment with the learners.”

Get more information about what it’s like for teachers when their school or district adopts a portrait of a graduate in The Portrait of a Graduate in Practice stories—print and audio. You’ll find tools they use, descriptions of lessons and project designs, examples of work that students in their schools have produced, and ways they are rethinking elementary school and middle school as well as high school.

Photo at top courtesy of Da Vinci Schools.