The New "I Do, We Do, You Do"

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Balancing Several Modes of Instruction in a Single Classroom

When I began training as a math teacher, I learned a simple model of instruction: “I Do, We Do, You Do.” I’d solve a problem in front of the class as my students took notes, then we’d work through an example or two together, then I’d let my students practice it on their own. In this way, I’d achieve an elegant balance between three important kinds of learning: teacher-led, collaborative, and individual. Nice and easy.

I quickly found this model almost completely ineffective in a real classroom. The “I Do” was problematic: some students saw the solutions right away, some lacked the prerequisite skills to see it at all, and some who were absent or late missed it altogether. The “We Do” was problematic: some students were eager to dominate class discussion, while others were hesitant to speak up at all. (Putting them on the spot with cold calls did NOT help them find their confidence.) And the “You Do” was problematic: my practice problems were inevitably far too easy for some students and all-but-inaccessible for others, many of whom who had severe learning gaps. The result was that few of my students learned much of anything.

What I liked about the “I Do, We Do, You Do” model, however, was that balance it struck between teacher-led instruction, student collaboration, and individual practice. I knew from my own experiences as a student how important each kind of learning can be, and as a professional I know the value of the skills students develop: listening, taking good notes, collaborating, and self-direction. My challenge, then, was to incorporate these different types of learning into a classroom that didn’t bore my faster learners or leave my slower learners behind, and do so in a way that would give each student an equal opportunity to participate and achieve mastery.

Here’s how I did it:

- First, I converted teacher-led instruction from front-of-the-class lectures (which I usually spent struggling to manage student behavior anyway) to instructional videos, which I created using a tablet at home. I also printed off copies of my video slides, so that students could take notes as they watched my videos.

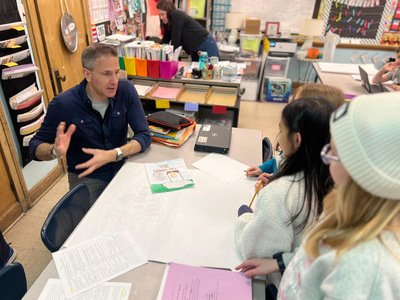

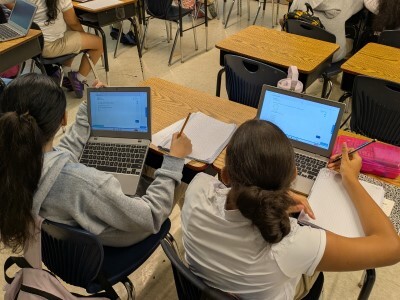

By watching my videos, my students still got the “I Do” experience—watching me solve a problem, and taking notes—but they got several other nice features as well: they could rewind if they missed something, fast-forward through anything they already knew, and watch at home if they were absent or late. Plus, by embedding my videos in Edpuzze, I could insert periodic check-for-understanding questions (in a much lower-stakes setting than asking in class) and track student engagement. It was just like lecturing… except much better. - Second, I designed classroom structures that encouraged collaborative learning. After each instructional video, I created an in-class assignment that students could do either individually or in groups; I encouraged students to work together and designed flexible seating that allowed them to do so. As I was no longer lecturing, students became free to work together throughout each class period—and I became free to work closely with individual students—throughout class time. They took advantage of this autonomy and started collaborating authentically.

When I tell people that my students use computers to watch videos in class, they often assume that my students spend their days simply staring into screens. Far from it! The self-paced learning environment that instructional videos create means that there’s actually more “We Do” than ever before. - Finally, I instituted individual mastery checks at the end of each lesson. These are short assessments that students must complete alone to demonstrate that they truly understand a lesson’s content and can apply their knowledge without anyone else’s assistance. If a student shows mastery, she receives credit and moves on; if not, she gets feedback and the chance to revise and reassess. This process ensures that no student advances into content for which she is not yet prepared.

By instituting this policy, I captured the essence of “You Do” as well—students are forced to problem-solve without assistance, but know that if they fall short they’ll be given the chance to succeed the next time around. It removes much of the traditional anxiety around assessment and prepares students for the larger individual assessments, like standardized tests or semester exams, that they’ll face throughout their educational careers.

In writing this piece I don’t mean to relegate “I Do, We Do, You Do” to the pedagogical dustbin. There’s plenty in that model that really works! Where it falls short, though, is in the assumption that all students should progress through the same content in the same amount of time; both my experiences and those of the teachers I’ve trained show that this simply isn’t how learning works. It’s time we take what works from this model—the balance between styles of learning which it emphasizes—and update it, to build classrooms that meet every learner’s unique needs. Our students deserve nothing less.