Enabling Change

When Humans, Not Systems, Run Schools

Topics

Next generation learning is all about everyone in the system—from students through teachers to policymakers—taking charge of their own learning, development, and work. That doesn’t happen by forcing change through mandates and compliance. It happens by creating the environment and the equity of opportunity for everyone in the system to do their best possible work.

The districts in NGLC's change management project have transitioned to home-based learning with rapid design of new systems and communication, propelled by their professional cultures of distributed leadership.

“The only way to discover the limits of the possible is to go beyond them into the impossible.”

–Arthur C. Clarke

We are all—globally—learning right now about the power of systems. The U.S. and most other nations failed to build the systems that might have prepared us to meet the challenges presented by a pandemic. That’s clearly true for healthcare response, but it’s also true for, say, state unemployment systems. We’ll learn this fall whether it’s true for elections and voting.

In public education, where systems have generally ruled the roost for decades (think: accountability, testing, sprawling federal and state regulatory requirements, restrictive bargaining agreements, immoveable governance models), the big questions emerging from universal school building closures due to COVID-19 have been, after food and safety were addressed: “Who’s got wifi and access to devices? Who’s got the curricular systems in place to bring ‘school’ into every learner’s home?”

Perfectly good questions to ask. They’re just not the most important.

The entrance to the district office at Arcadia Unified School District. (Courtesy of Andy Calkins)

For the past 18 months—building on our previous eight years of catalyzing learning and school redesign—NGLC has been studying and learning alongside six school districts that are serving as advance scouts for the other 13,000 districts in the country. These half-dozen communities have committed, we like to say, to being the change they seek for kids. They seek a set of learning approaches for their students designed to help them develop true readiness for the demands of 21st-century life—personal agency, resilience, adaptive resourcefulness, curiosity, and the will and self-efficacy to embrace a lifetime of learning.

And, just as important: these districts understand that the only way that will happen for all of their students is if those attributes also describe the professional culture and daily operating habits of the adults in their schools.

These districts are subject to the same web of systemic restraint as every other public school district in the country. They are relentless internal system-builders as well. They love systems—up to a point. Mostly, they are aggressively pro-human. Their human beings, not the internal or external systems, are running the show.

Moreover: the students are deep participants in running the show. How better to prepare them for the lives that their century, society, economy, and planet will require them to live?

Sounds great, doesn’t it? But I know the questions you’re asking. What does this look like in practice, how have these districts gone about making it happen, and what results are they seeing from their work?

All of that will be emerging from NGLC’s next gen change management project this summer and over the course of the next year. The Carnegie Corporation of New York, which supported the original phase of research, recently awarded NGLC a $500,000 renewal grant to complete the development of this promising work.

This 2020 spring of COVID-19, meanwhile, has created a sudden, dramatic crucible that is testing the fortitude, operational healthiness, and agility of every school and school district in the country. None of them, of course, could have anticipated such a pervasive global and local emergency of these proportions. But it’s becoming clear as the spring wears on that some schools and districts are supporting more learning under these stressful conditions, more deeply, and for more of their students than others. (NGLC is leading a group of partner organizations, in fact, to conduct qualitative research into the factors that appear to have contributed to that agility.)

The districts in our change management project have met the challenge of transitioning to home-based learning with rapid design of new systems and communication, fired up and propelled by their professional cultures of distributed decision-making and leadership.

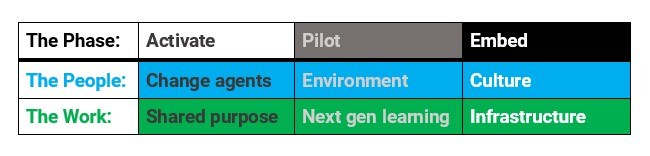

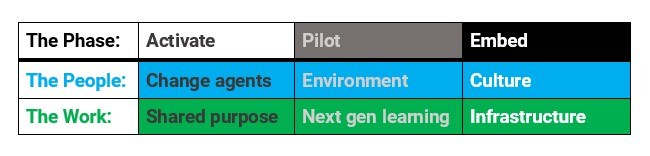

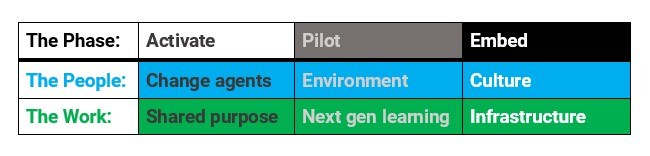

The stories we’re hearing from them fall neatly into the emerging framework for transformational change that is emerging from this project, and from a partner initiative called the Deeper Learning Dozen. The framework shows a relentless pattern of inquiry and innovation-design cycles running through both the human-powered side of this approach (“The People”) and the systems, structures and processes side (“The Work”).

Activating the Heart and New Vision for Change

Cultivating staff, students and stakeholders as change agents (the People part)… to co-construct a renewed, shared purpose (the Work part).

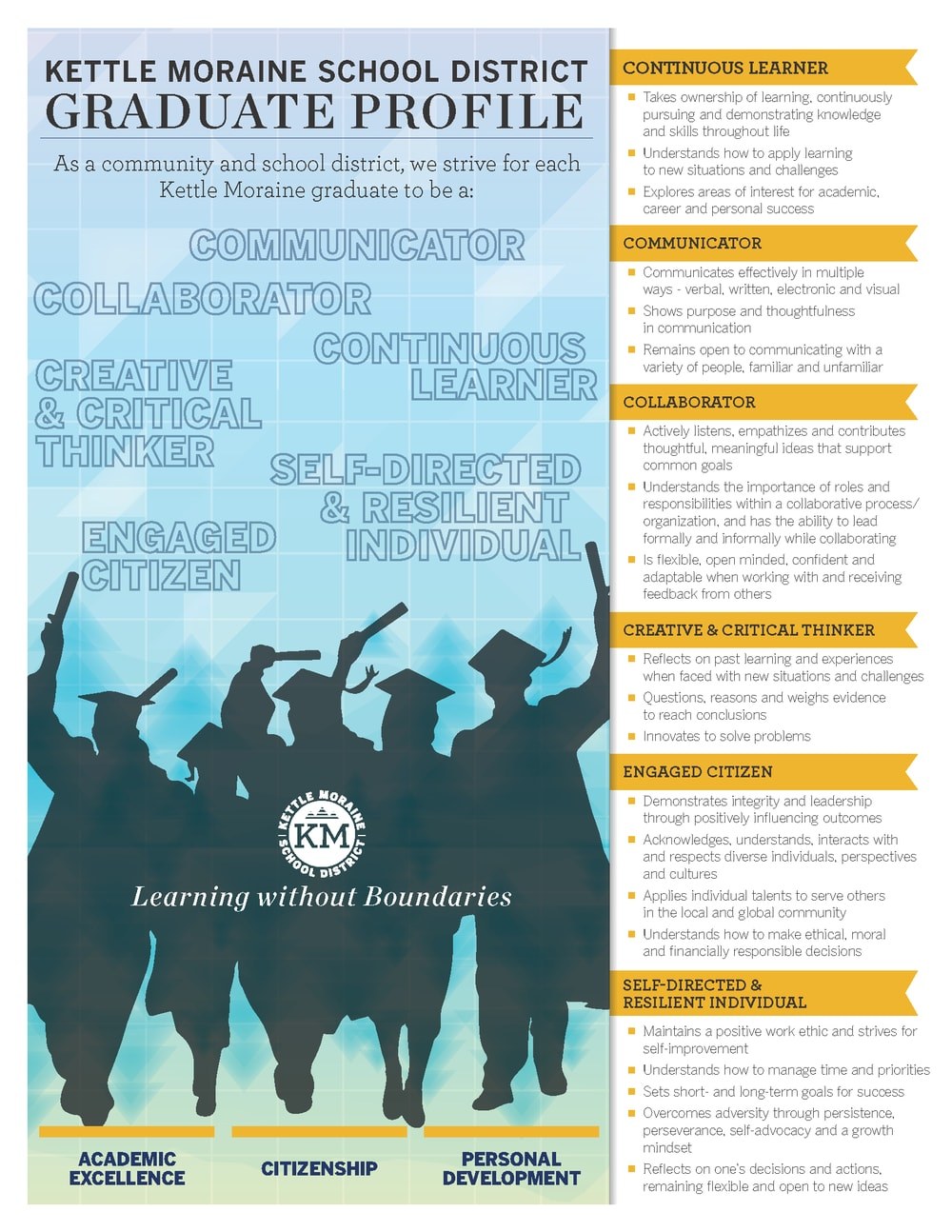

Re-setting, together with all stakeholders, a community’s vision for student success seems to be the right place to start, and the “jet fuel” that powers and sustains the entire change process. Kettle Moraine School District (WI), one of the six districts in NGLC’s change management cohort, launched its Learning Without Boundaries initiative a decade ago with a vision re-set, and still uses its graduate profile to shape its work today—including in its response to COVID-19.

“One of the big decisions we had to make,” superintendent Pat Deklotz told us, “was what does all of this [COVID-19 and school building closures] mean for grading? If you walk away from letter grades, aren’t you putting high school students at a disadvantage when it comes to college admissions? We wanted to stick with letter grades but allow teachers to do it in a different way. It’s always easier to improve on something than to invent something, so we always start with a small group, and then it builds out from there through our very distributed-leadership model.

“We went back to the graduate profile,” Pat continued, “thinking about all of the kinds of evidence of learning that could indicate how students are developing the attributes in the profile. The process ended up being a good test of our ability to lean into the graduate profile and use it the way we intended. As an example: one teacher told a story of a KMSD high school student, living with his grandparents and working in the healthcare industry, who moved into the garage of their home to protect them. That goes straight to the attributes in our profile of self-direction and creative problem-solving. We include that right now in what we’re calling ‘the preponderance of evidence’ of student growth.”

Piloting and Developing New Muscles for Change

Building trust and new ways of working in an inclusive environment (the People part)… to transform key elements of learning and school design (the Work part).

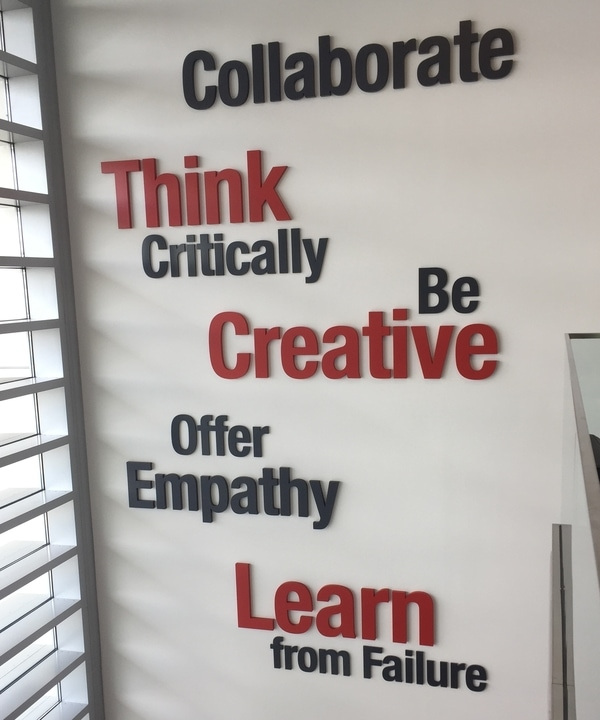

Arcadia Unified School District (CA) wears its cultural watchwords on its sleeve, on the wall facing the public entrance to its district headquarters. (See photo at top.) But this isn’t window dressing. The social network map shown below reveals the amount of intra-district/school connecting that went on during the first week that district schools were closed this spring. Chief Strategy and Innovation Officer Greg Gazanian calls it “beautifully dense.”

(Courtesy of Arcadia Unified School District)

The graphic demonstrates how years of enlisting Arcadia teachers and school leaders in leading cycles of inclusive innovation design focused on high-priority aspects of Arcadia’s learning model have paid off during this moment of extreme need. Over time, Arcadia’s adults (and students) have developed new convictions about “how we do things here.” They are bringing those convictions to this challenging COVID-19 era.

(Courtesy of Vista Unified School District)

The same dynamic applies in Vista Unified School District (CA), where networks are so strong and leadership so distributed that the district established, in three weeks, a community-wide Vista Virtual School that reimagines their entire learning model and service delivery systems. “Almost every principal in the district,” says Nicole Allard, the executive director of innovation and educational excellence, “is leading a districtwide project as part of this effort. It has been all about giving people at all levels permission to try things out. That’s the only way we could have gotten something like this done.”

Imagining and Embedding New Systems for Change

Establishing an organization-wide culture of inquiry and improvement (the People part)… to develop infrastructure that supports continuous and equitable next gen learning (the Work part).

St. Vrain Valley Schools (CO) has worked on reinventing its human-capacity-and-culture side and its systems-and-infrastructure side so hard and for so long—since 2009 under the leadership of Dr. Don Haddad, superintendent—that it now takes pride in the ways its systems proactively spark, enable, support, monitor, and sustain its innovations and, well, its humans. The most mature models among our six districts, like St. Vrain, have built such strong muscles and cultures of trust and collaboration that they have been able to take on some of the most deeply embedded restraints of traditional American public education.

All of that, says middle school principal Anthony Barela, enabled St. Vrain to “pivot quickly and without simply overlaying the brick-and-mortar school-based learning model onto the home.” The district set a suggested pattern of “two inputs and two outputs per subject, per week,” and left it up to teachers and schools to adapt that general advice as needed. The district’s extensive tech infrastructure, supplemented by a two-week sprint to ensure broadband access from every home, has played crucial roles in connecting families with the district and educators with each other.

(Courtesy of St. Vrain Valley Schools)

“People, like all life,” wrote Margaret Wheatley, “only change when they allow an event or information to disturb them into voluntarily letting go of their present beliefs and developing a new interpretation.” We’ve had to let go of a lot that we thought we knew about how to live, as the pandemic has turned lives upside down. In education, we’re forced to reinterpret nearly everything we believed about how we teach. But when the crisis settles, will we go back to the way things were, or will we consider new interpretations, to use Wheatley’s phrase?

The six districts we’ve been studying either used or manufactured an event that brought about the deep, fundamental changes in organizational culture they’re relying on right now. How many dozens… hundreds…. or thousands of schools, districts, and communities might use this unique moment in the history of K-12 education, over the coming months and years, to do the same thing?