Reimagining Assessment

When the "Iceberg Problem Really Hits Hard:" NOLA Educators Talk Policy, COVID, and Learning Loss

Topics

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

Learning loss and unfinished learning is common in middle school and especially problematic in math. And that was a big deal before COVID.

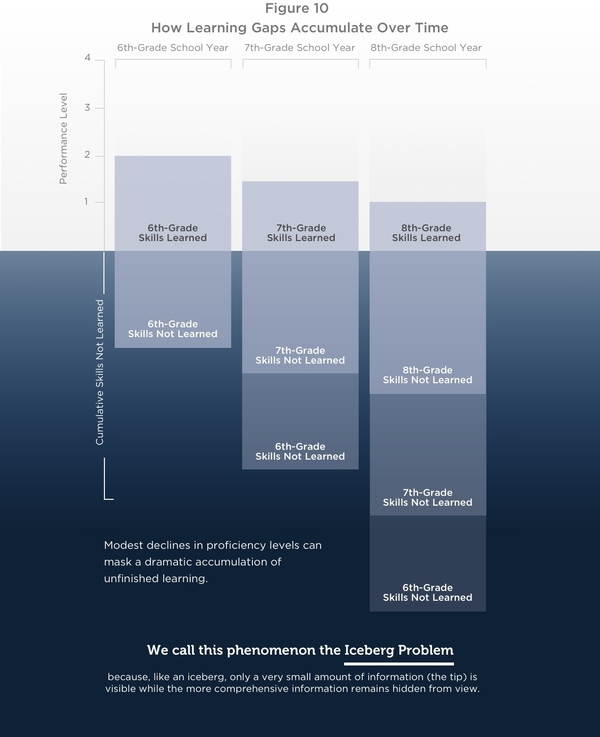

Learning loss and unfinished learning are common issues in the middle school years. They are especially problematic in math where it is inherently cumulative—concepts and skills build upon one another as students advance through school.

And that was a big deal before COVID.

As documented in The Iceberg Problem, summative assessments and the connected federal accountability system push schools to focus narrowly on grade-level proficiency, which allows unfinished learning to accumulate. But the pandemic will almost certainly exacerbate unfinished learning and unaddressed learning losses—especially for underserved students.

So how are teachers and school leaders responding to these unprecedented challenges? How are they planning for their schools to reopen, and how can policymaking play a part in the process? To find out, we spoke to Jolene Galpin and Matt Driscoll, of Mildred Osborne Charter School in New Orleans, Louisiana, a Teach to One partner school.

Jolene Galpin, executive director, and Matt Driscoll, director of curriculum & instruction of math, of Mildred Osborne Charter School in New Orleans. (Photos courtesy of Galpin and Driscoll, respectively)

New Classrooms: Jolene and Matt, thank you for setting aside time to talk about the Iceberg Problem and Mildred Osborne’s response to COVID. To start, how are you, your students, and your staff doing?

Jolene: Overall, our staff has been reporting they are doing well and thankfully very few (less than five) have personally been sick or experienced a loss of a loved one as a result of COVID-19. Unfortunately, that has not been the same for our students. It feels like almost on a daily basis we are receiving word from families that a parent/guardian is hospitalized or a loved one has passed away.

As you can imagine, this weighs very heavy on my mind and heart, and that of our team. This reality has also caused our leadership team to constantly reflect on what we are expecting students to do, as it relates to distance learning, to ensure we are prioritizing physical and emotional well-being just as much as academic achievement.

New Classrooms: Even under ‘normal’ circumstances, when do you typically see students start to fall behind in mathematics?

Matt: There are always kids who are behind in kindergarten, but you really start to see a drop-off around fourth grade. It’s a big year content-wise. Third grade introduces a whole bunch of new concepts (multiplication, division, fractions) at a deeper conceptual level. Fourth grade math assumes students grasp a lot of that deep conceptual thinking and fluency and then throws it into overdrive. Some students can get by in fourth grade, but there’s another major shift in sixth grade when they start on a brand new set of standards that, again, assumes deep conceptual understanding of and fluency with those prior skills. We see kids across the city who demonstrate significant deficiencies with fluency and calculation, to the point where they struggle to process new concepts. So fourth grade is where we start to see the problems accumulating, but the Iceberg Problem really hits hard in sixth grade.

Courtesy of New Classrooms

New Classrooms: Jolene, as a former principal in Chicago, what are some key differences you’ve seen in how large districts measure student learning?

Jolene: While I was a principal with Chicago Public Schools, the accountability framework (School Quality Rating Policy, or SQRP) placed a much heavier weight on student growth scores over proficiency scores, as demonstrated on the NWEA math assessments for K–8 schools.

Under the accountability framework in Louisiana—and exactly as The Iceberg Problem outlines—I believe more school leaders and teachers feel pressured to focus on grade-level instruction at the expense of dedicating adequate time to provide intervention or remediation. Even with some of the blended learning models that I know have been implemented across the city, the digital learning component is often not personalized to students’ needs, or focused on filling gaps, or building foundational skills. At Osborne, I am lucky to have a team of leaders, teachers, and other staff that believe it is important to find the balance between rigorous, grade-level instruction and true, personalized learning. The literacy and math intervention and enrichment blocks we have four times a week help fill the gaps for many of our students performing below grade level; they also allow us to provide enrichment opportunities to those students who are at or above grade level.

New Classrooms: What would a better system look like?

Matt: Even though we try to stay in our lane, we think about this all the time.

At the highest level, education needs more funding, period. We need greater funding to increase access to early education, especially for students of color, building more Head Start-like programs and stronger pipelines to get into those programs.

In terms of reimagining the way that our school functions, we would love to see a more individualized focus on math instruction for students who we know are behind. This means not just individualized content progressions, but also individualized schedules. We have an intervention program for reading and math, but every student receives the same amount of instructional time. It would be more advantageous to focus these kinds of resources—time being the most valuable resource—on students who are behind.

At a systems level, shift the focus more toward growth. Then schools wouldn’t focus on teaching tricks to do well on tests. They would focus more on teaching the whole child and making sure students really understand, in this case, the math concepts that are essential to their long-term growth.

Jolene: I’m grateful for publications like The Iceberg Problem because I feel that it is extremely important for policymakers, as well as school leaders and educators across the nation, to have this debate and hopefully revisit the way we educate our children—particularly those who do not demonstrate grade-level proficiency—with the ultimate objective front of mind.

New Classrooms: Looking to the future, how do you see the Iceberg Problem in the context of COVID from an academic perspective?

Jolene: Our academic leadership team is thinking about a number of things as it relates to curriculum and assessment. If we do return for the fall, do we spend a month doing remediation, or do we jump right into new content? What will be the best way to assess the COVID slide and monitor progress toward grade-level proficiency? If we’re still engaging in distance learning, how can we create more engaging learning experiences in the live digital instruction format?

Regardless of the scenario, we know personalized learning will be more crucial than ever. It will be a top priority for the upcoming school year—second only to supporting the social and emotional needs of students and staff. By that I mean professional development will be focused around supporting personalized learning; more effective individual student goal-setting and progress monitoring; and assessing the current programs we have and how we are utilizing them.

As to how COVID/school closures will affect our accountability framework at the state level, I am not entirely sure. I do know that district and state education leaders, as well as policy makers, are thinking about this and, I believe, will need (and want) to take the COVID slide into consideration as they determine what the accountability framework will look like for the upcoming year or two. My hope is that the student performance calculation includes a much heavier weight on growth and that the state policy makers realize this method of scoring schools is what is most equitable for the long haul.

Photo at top courtesy of New Classrooms