Why Schools Need to Change

Who’s Really Responsible for College and Career “Readiness”?

Topics

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

What if we flip the “college and career readiness” question on its head and asked whether colleges and careers are prepared to educate and employ our youth so the burden of readiness doesn’t fall solely on students?

“College and career ready” has been a catchphrase of high school reformers for decades. I can’t tell you how many times I have used variations on the term in meetings, articles, or funding proposals. Seems noble enough, right? Equip young people with the skills they need to succeed. Who wouldn’t want that?

The problem isn’t what we’re asking of students. It’s what we’re not asking of everyone else.

We’re deeply concerned that students aren’t ready for the workplace. Yet it is abundantly clear that the workplace is not remotely ready for them, with employers struggling to attract and retain talent.

We’re so obsessed with making students “college ready” that when we got serious about writing national standards aimed at that goal, we asked university faculty to take the lead in defining what that term meant. But it’s unclear that as a sector, higher ed can claim to be especially good at educating emerging adults. About 60 percent of students who start college actually earn a degree, with that figure significantly lower for low income and BIPOC students. If a high school posted a graduation rate like that it would be labeled a dropout factory.

When I argue for competency-based approaches to K-12 and higher education, I routinely cite research on the skills students need to succeed at work or in college, a lot of which draws on input from higher ed or employers. But it’s worth asking whose interests are being served by college- or employer-driven definitions of readiness. Are they based on what is best for young people, or what is best for them?

With notable (and laudable) exceptions, higher education has always placed a relatively low premium on pedagogy, with career advancement for university faculty largely dependent on scholarship. Admitting and enrolling students who can overcome indifferent (or even bad) teaching and still learn something keeps all of the incentives in line.

Similarly, employers have a pretty dismal track record when it comes to learning and development, and an even worse history of identifying, recruiting, and retaining diverse talent. Wouldn’t it be easier if new employees showed up prepared to assimilate to organizational norms, already knowing most of what they needed to know?

What if we looked at a student who somehow made it to college or into a job interview despite a pandemic, neighborhood instability, and (often) substandard schooling as having a set of superpowers?

In my last post on listening, I noted that in schools being a “good listener” too often means simply being compliant. When it comes to postsecondary transitions, I wonder if being “ready” just means not asking too much of the institutions who effectively shape the lives of emerging adults. It reminds me of schools that resist change because they are labeled “high performing,” never realizing that their economically advantaged students came in the door doing well on the very tests the school claims credit for.

What if we flip the readiness question on its head? What if we looked at a student who somehow made it to college or into a job interview despite a pandemic, neighborhood instability, and (often) substandard schooling as having a set of superpowers? After all, these young people are highly resourceful, emotionally intelligent, and often creative. Instead of wedging them into the Procrustean Bed of an “ideal” employee or student, what if we bent our work and learning environments to leverage those talents?

None of this is to say emerging adults don’t have a lot to learn, or that every habit or skill they have is just fine the way it is. The need for students to get ready has never been in question. But the burden of readiness should not fall solely on them.

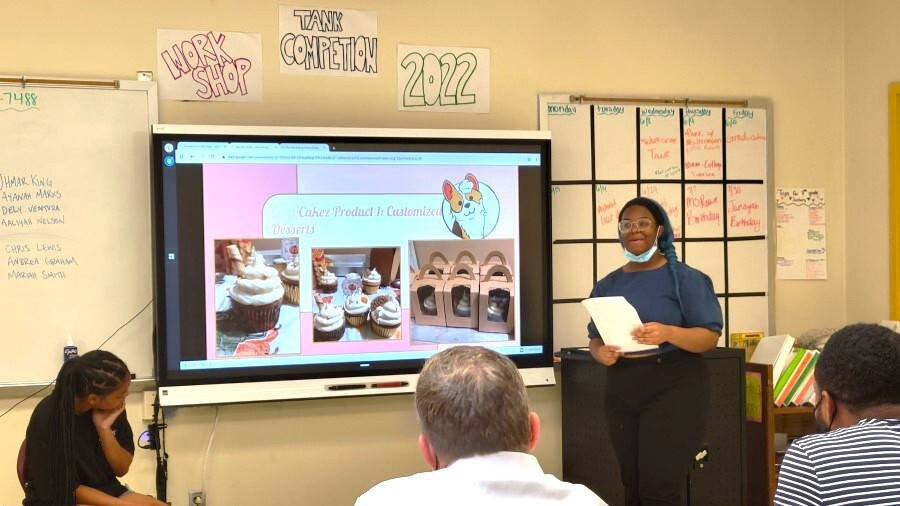

For higher ed, readiness means prioritizing teaching quality, reorienting the curriculum around skills instead of content, integrating more real-world learning opportunities, crediting students for what they know and are good at, retiring the entire deficit-minded category of “remediation,” and finding more ways for students to attend school part time and still receive financial aid. (This is precisely what we are trying to do in a new postsecondary program called WorkshopU, and our colleagues at College Unbound are doing amazing work in recognizing and crediting skills and expertise developed in the workplace.)

For employers, readiness means expanding hiring and recruitment networks, adopting a more holistic approach to learning and development, stepping outside of their comfort zone in hiring and advancement decisions, and partnering with organizations that serve youth and emerging adults to build their capacity for mentorship, trauma informed practice, and real inclusion practices with the systems that support them. Future Focused Education’s X3 Internship program offers a promising example of what this could look like.

We all have a real learning curve here. All parties—youth, employers, and intermediaries—will get some things wrong along the way, and there needs to be some room for trial and error. But if we can learn from the process, we have a chance to balance the readiness equation, and maybe not require the least advantaged among us to do all of the work.

All photos courtesy of Workshop School.