Whole-Child Touchstones for COVID Pivots (and Beyond)

Topics

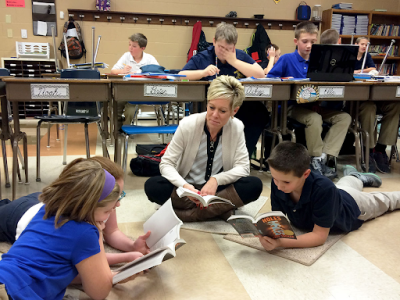

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Three strategies for whole-child development have persisted as important touchstones for learning by prioritizing relationships, well-being, and agency.

Think back to the first few months of 2020, when teams of classroom educators, students, and learning designers were busy co-creating versions of more personalized, student-empowered, and future-ready learning in a pre-pandemic world. No rose-tinted glasses—the distribution of empowering models was certainly not yet equitable, and the impact on broader systems change felt soul-crushingly slow. But undeniable changes in the global economy and society were awakening educators to the need to transform learning in ways that would empower their students to thrive in a world of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA).

Then, COVID (an unwelcome vindication of the need to prepare for VUCA if there ever were one!).

Educators, students, and parents were plunged into a new, remote world, applying heroic efforts to deal with the sudden disruption. After initial attention to health and safety, online logistics, and, vitally, how to provide equitable access, the issues raised by front-line educators broadened:

- How do I deal with the human needs the pandemic has raised for my students—withdrawal, depression, anger, and trauma?

- How do I keep my students engaged in learning at a distance? How do I get them to log on, let alone maintain and build on my relationship with them?

- How do I prune content in order to focus on these things (and because online learning seems to take twice as long to prepare!)? How do I, and my students, get a sense of what they’ve learned when old style assessments don’t work well remotely?

The pandemic brought to the surface systemic injustices that always existed but weren’t always seen or acknowledged. And then the national reckoning with systemic racism following the killing of George Floyd intensified the need to center equity and social justice in education as in other areas of life.

Over the spring and summer, classroom educators and thought-leaders, meeting in forums including From Gathering to Transformation and Silver Lining for Learning, began to consider how we might leverage all this disruption to accelerate the transformation of learning when school opened again in the fall. (Or as Yong Zhao put it, “not to return to the same education after we return to the same school.”)

However as it gradually became clear that many schools were “returning” to further remote and hybrid learning, all energy turned to how to manage the here and now. Implementing a whole new school year amid continued health, economic, and social concerns brought additional questions to the fore:

- How do we address health and safety concerns of in-person learning during a pandemic while also honoring student, family, and educator choice about whether to return to school buildings?

- How do we address not only equity in access to technology, but also equity in remote learning environments and in-person supports, all of which are deeply impacted by systemic racism?

- How do we deal with the realization that, under pandemic conditions, teachers and schools can’t do all the jobs we have come to expect from them? See Jessica Calarco’s analysis of the provision of hands-on-instructional support, childcare for working parents, and children’s social interaction as well as Andy Calkins’ related equation from the school perspective.

It’s difficult not to see this as the most challenging, even overwhelming, school year ever. But as the Aspen Society’s white paper, Recovery and Renewal: Principles for Advancing Public Education Post-Crisis, asserts, “The current moment cannot be defined only by responding to the pandemic. Even before the crisis, profound questions were on the table about the role of education in society and what education outcomes are most important for students to be ready to thrive as adults and become contributing members of society.” What if the essential principles of learning transformation from “before” still hold? What if the core principles of student-centered, holistic, and authentic learning become more important than ever—as touchstones for addressing the pandemic and the push for greater systemic equity, as well as longer-term change?

See how one school system is thinking long-term about education after COVID-19 with equitable whole child well-being at its core.

Read "Open the Doors"

Next Generation Learning Challenges’ MyWays Student Success Framework (which I co-researched and -authored) is one of a number of pre-COVID initiatives that combined the strategies and perspectives of innovative educators and schools with current research to illuminate such principles (other examples include Education Reimagined’s Learner-centered Vision, and LEAP Innovation’s Personalized Learning Framework). One of the most important foundations that emerged across this pre-COVID transformation work was the need to broaden education outcomes from narrow academic achievement to whole-child well-being and development.

While previously many schools found making this transition challenging, as this fall progresses, there is a growing movement to focus on the developmental needs of our learners as whole beings—prioritizing health, social and emotional needs, as well as the development of broader, deeper personal outcomes such as identity, agency, and purpose. This explicit attention to human development acknowledges the primacy of more fundamental human needs during a time of crisis and aligns with the guidance of the learning sciences that students are unlikely to learn effectively in any event if these broader needs are not met.

During a recent ASU-GSV session conversation on innovating for success during COVID put together by Sujata Bhatt of Transcend, Tom Rooney, the superintendent of Lindsay Unified School District, confirmed that the best driver for addressing the real trauma among learners was “to become even more learner-centered, giving every learner what they need,” and that during the building closures, “focusing on our Lifelong Learning Standards became more important than ever before.” Gia Truong, CEO of Envision Education, explained that during COVID, while traditional guardrails like instructional minutes “crumbled,” in their place “the most important thing was the [broader outcomes] Graduate Profile,” in addition to “attention to wellness, love and care.”

Three “Whole Child” Touchstones for COVID Response and Beyond

In particular, as next gen learning educators, schools, and districts implement their fall plans, three (interconnected) strategies for whole-child development have persisted as important touchstones:

- Focus on social and emotional health and well-being1

- Build learner agency, identity, and purpose2

- Expand learning environments by centering family engagement and community connections3

None of these strategies ignores the pursuit of knowledge and skills, but they approach the learning of content from a human development perspective that prioritizes relationships, well-being, and the development of agency, purpose, and connection that can be pursued remotely or in person. Leading educators who are pivoting in COVID conditions using these three strategies provide examples of serving urgent need while furthering longer-term transformation.

1. Focus on social and emotional health and well-being.

SEL leaders like Turnaround for Children and Valor Collegiate Academies were already prioritizing the health, mental health, and broader social and emotional development of their learners. The COVID health and economic crises and national attention to systemic racism revealed, more plainly than ever, the need to address learners’ needs in these areas through strong relationships. The stark variability of home learning environments has helped us to see the extent to which children’s broader lives impact their learning and development, and the range of holistic supports that must be provided to move toward equity.

Some examples:

- Brooklyn LAB, an NGLC grantee and XQ Super School that has long focused on supporting the social-emotional well-being of its high-need population, has collaborated with City Year, EL Education, The Forum for Youth Investment, Turnaround for Children, and others to develop a Success Coaching Playbook. The playbook details how to provide students with support in a variety of learning contexts, including remote, in-person, one-on-one, and small group instruction, to address student trauma, family stressors, and learning loss.

- Adams14 School District in Colorado will be trialing remote counseling to address the expected rise in mental health needs of students and adults, while limiting in-person contacts.

- The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) has a new initiative related to the development of SEL during COVID. The Search Institute has a helpful checklist for Building Developmental Relationships during the COVID-19 Crisis. And the Family-School Collaboration Design Research Project has drawn on experience in Salt Lake City to provide recommendations for improving relationships with families.

2. Build learner agency, identity, and purpose.

A central goal of next gen learning is enabling learners to direct their own learning, and to engage their strengths and interests (see, for example, The Deeper Learning Dozen and Summit Public Schools). With the major decline in contact time during emergency remote learning in the spring, both teachers and parents lamented that even high school students lacked these skills. Schools that shifted to remote learning most effectively seemed to be those that had already built learner agency and learner purpose through deeper and more authentic learning, using a variety of approaches such as competency-based learning, project-based and experiential learning, and personalized learning approaches that provide significant student voice, choice, and self-direction.

Some examples:

- Brooklyn LAB (see above), with the Center for Black Educator Development, Character Lab, NCLD, and others, has recently released a Back to School Learner Identity and Agency Guidebookand, as Eliot Levine of the Aurora Institute points out, is a good example of how competency-based education can facilitate “a smoother transition to the shifts in learning required by the pandemic.”

- PBLWorks lays out the case for why PBL so fits current needs, providing a more promising approach to learning loss than remedial units, as well as enabling students to engage in independent and collaborative work that frees teachers for small group and individual skill instruction. Ben Owens of Open Way Learning also provides tools helpful for taking PBL remote and provides examples of teachers leaping into PBL for the first time in the current environment. Shelby County (KY) Public Schools teachers, after struggling to replicate the normal school day remotely, turned to PBL, which helped engagement and learning take off.

- The longstanding networks of deeper learning schools are also offering helpful tools for more authentic learning and performance assessments, such as the Deeper Learning Hub distance-learning PBL courses and Envision Learning’s Virtual Portfolio Defense guide.

- For more on designing and implementing PBL in a virtual landscape, refer to Da Vinci Schools’ recent Transforming Learning Conference, and its Da Vinci Institute.

3. Expand learning environments by centering family engagement and community connections.

Many of the educators focused on better serving the whole child and better preparing them for the real world of today and tomorrow were already employing an “open-walled” approach, engaging a “wider learning ecosystem” through connections to the real world, to learners’ communities, and to a broader range of adults. (See, for example, Schools That Can and Northeastern’s NExT network of K-12 experiential learning schools.) This expansion of learning outside classroom walls and in connection with adults other than classroom teachers has suddenly become a necessity, whether learning is happening in person, remote, hybrid, or supplemented by learning pods. While the social distancing COVID world is by no means the ideal environment, creative educators, parents, youth developers, community-based educators, and employers are embracing opportunities to connect.

Some examples:

- Big Picture Learning schools, which have long focused on personalization, relationships, independent organizational skills, and learning outside the classroom have been able to leverage these strengths during their COVID pivots. Big Picture, known for their integrated internship experiences, has had to adapt in different ways, but the adults and students alike are drawing on the challenge that’s long been part of the model: figuring out “what do you do when no one tells you what to do.”

- The CAPS (Center for Advanced Professional Learning) network put together a virtual career week, and its students have been able to keep learning through industry certification programs online. In the Little Rock School District CAPS program a number of industry partners are offering flexibility for hands-on career-based learning and mentoring, bringing an office trailer onsite and meeting with students via Zoom. MetWest High School in Oakland, California, secured internships with GenesysWorks, a national organization that pairs underserved students with work opportunities. Many of those partners were able to transition to remote experiential offerings.

- A range of after-school, enrichment, museum, and other out of school time educational providers are pivoting to provide small pod-style learning environments, ranging from simply overseeing children participating in school-based remote programs to more substantive learning input with interest-based, real-world, enrichment learning. San Francisco’s Department of Children, Youth, and Families is coordinating 40+ Community Hubs for high-need students. The YMCA of Greater Nashua, New Hampshire, is supplementing help with district remote learning with an evidence-backed project-based learning model.

In some places, the coming year is likely to see an increase in online lectures and rote learning online, focusing on what is easily “transmitted” and “tracked” through technology. But educators are also finding new ways to develop learners as whole beings in broader environments with wider scope. (For more insight into schools addressing these three whole-child learning principles under a variety of pandemic situations, see Transcend’s Leading During Coronavirus series and Resource Library, as well as their collaboration with the Christensen Institute’s Canopy project.)

As long as the current crisis persists, we will be challenged to think ever more creatively about how to develop the whole child remotely, online, and/or in small groups inside or outside the school walls. Then, when the health crisis abates to the extent it will, our challenge will be instead to think creatively about how not to go back to school as we knew it but to move forward. We will need to find ways to add what we’ve learned during the pandemic to better address whole-child development. We will need to focus on relationships and well-being and the development of agency, purpose, and connection more than ever before.

1 Aspects of the MyWays Student Success Framework that those focusing on social emotional development and well-being might find helpful include: Report 1, Introduction and Overview of the MyWays Student Success Series, which references the Human Development (along with Education and Work-Related) success frameworks synthesized for the work; Report 5, Preparing Apprentice-Adults for Life After High School; and especially Report 7, Habits of Success — for Learning, Work, and Well-Being and its practical one-page primers. (Andy Calkins, Dave Lash, and I co-developed MyWays based on the work of NGLC’s network of next gen and other pioneering schools and districts, as well as the latest research.)

2 For collations of pioneering practice and recent research on learner agency, identity, and purpose, see MyWays Report 4, 5 Essentials in Building Social Capital, and especially Report 11, Learning Design for Broader, Deeper Competencies, including Construct 1: Whole Learning Through Junior Versions and Construct 3: Levers for Capability and Agency.

3 For ways to open up the learning landscape, see MyWays Report 11, Learning Design for Broader, Deeper Competencies, Construct 2: The Wider Learning Ecosystem. To start exploring the possibilities, see also this introduction to NGLC’s Real World Learning Toolkit.

Photo at top by Redd Angelo.