Professional Learning

Writing Not to Win But to Learn at Oakland Unified School District

Topics

Educators are the lead learners in schools. If they are to enable powerful, authentic, deep learning among their students, they need to live that kind of learning and professional culture themselves. When everyone is part of that experiential through-line, that’s when next generation learning thrives.

OUSD turned the three steps a U.S. presidential candidate took in a famous speech into a tool to help students address multiple perspectives in their writing.

With impeachment proceedings underway and a highly contentious presidential election around the corner, the tone and tenor of our politics has become increasingly strident. Politicians trade one liners on Twitter or attack colleagues on a debate stage with catchy phrases designed to be easily shared, liked, and promoted. They know that the stakes are high, and they are writing and speaking to win.

The contentious mood of our country is not new and has been influencing the mood in our classrooms. As a teacher of writing, I too wanted students to win their arguments. During my time teaching tenth grade in Oakland Unified School District (OUSD), students had to pass the California High School Exit Exam (CAHSEE) to graduate. One task on the exam was a five paragraph essay. To earn the highest score, students had to respond to a counterargument in their last body paragraph.

My colleagues and I would provide students with sentence starters like, “Some may think, but they are wrong because…” We were training students to think that they could strengthen their argument by debasing another person’s perspective.

A couple years after CAHSEE was eliminated, I was in a new role in OUSD supporting the development of the graduate capstone project, which consists of a research paper, oral presentation, and in some cases, an action project. I was discussing a research paper with OUSD teachers at Life Academy. The paper had received an “A” from a professor at UC Berkeley, but most of us had rated the paper at the emerging or developing level in the category of “multiple perspectives.”

Why?

We had scored the paper low because we did not see a place where the author named a counter argument and refuted it. While training our students to write to win, we had also trained ourselves to think that addressing multiple perspectives meant taking down someone else’s ideas.

Actually, what the author had done was more sophisticated. She was exploring other perspectives in order to reveal the complexity of the issue. One example is how she interrogated the role of violence on education. She cited evidence that showed teachers in poor communities enforce discipline in harsher ways than they would in middle class communities. She avoided blaming teachers by using phrases that recognize their intentions like, “While it is important to establish a safe environment, …”

Ironically, the rubric language for multiple perspective said that an advanced paper was supposed to “acknowledge and respond to questions or alternative interpretations to explore the complexity of the topic.” The student had accomplished this. Despite what the rubric said, we scored the paper based on our entrenched mental schema—write to win.

The teachers in that room realized that we had to shift our understanding of the assessment language for multiple perspectives. My colleague Camrin Fredrick and I would later design a PD session with OUSD capstone teachers to reflect on how we might teach multiple perspectives in a way that emphasized deliberate consideration rather than winning. We wanted to create a new mental schema—write to learn and understand complexity.

We began with a model text: Obama’s 2008 speech on the topic of race. In his first presidential campaign, Obama was facing criticism for his association with Reverend Wright who had made controversial statements about the United States. We listened to the speech and looked at a transcript which showed Obama doing three key things:

- Giving an even-handed description of another perspective

- Exploring why someone might have those beliefs

- Taking those ideas into account in expressing what he believes

These were the steps that became the basis for a tool that students could use to address multiple perspectives in their writing. The critical step is the second—to explore someone else’s beliefs, which means they are seeking to understand or empathize with another perspective. What we saw in a lot of student writing was that they briefly described another perspective and then quickly moved on to their argument.

We asked teachers to practice using the tool to make a simple argument about why chocolate ice cream is the best. Before they wrote, I shared why I think rum raisin is the best ice cream flavor. After hearing my rationale, their goal was to include their understanding of my reasons or to acknowledge the strengths of my reasons in their writing.

Their next task was to use the tool to revise examples of student writing that was either emerging or developing and revise it themselves so that it reached proficient or advanced. The teachers then had time to take these ideas and resources and adapt them for use in their classrooms. For teachers and students, “multiple perspectives” shifted from winning an argument to deepening their understanding of the complexity of the issue.

During a political campaign, winning matters. But once in office, elected leaders in a democracy need to switch mindsets and work with others to make policy and govern. Research writing is more akin to governing than campaigning. Students need to consider the evidence and empathize with other perspectives in order to reach a more nuanced and sophisticated understanding of the issue at hand. Teachers, then, should focus instruction on students writing to learn, not to win.

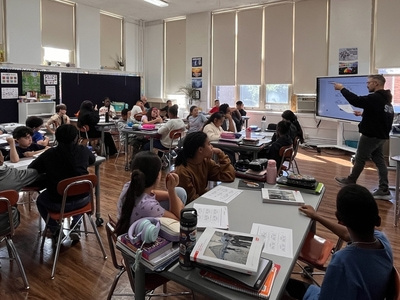

Photo at top courtesy of Young Whan Choi: Professional learning event with Oakland Unified School District teachers.